When you’re ushered into the chapel for a wedding, sometimes they ask you “bride or groom?” That’s to identify where you should sit.

I was thinking of that quaint custom as I came into the Berkeley Street theatre tonight for All But Gone, a fascinating hybrid presented by Canadian Stage & Necessary Angel. When they ask which side of the church are you sitting on, meaning are you sitting with the family of the bride or family of the groom, you don’t usually expect that everyone there is from one family and you’re all alone on the other side. But I could have sworn everyone there tonight was from Beckett’s family (meaning the spoken word/ drama side) rather than the opera- sung side, where i hang my hat. I listened afterwards to a fellow all charged up about what was done wrong, how they shouldn’t have been looking at us in the audience, that the instructions in the text are very clear (oh yes he knew his Beckett) that you can’t do it that way.

So of course when Krisztina Szabo and Shannon Mercer came out behind us, singing first quietly then more loudly & not entirely intelligibly, I wondered how he’d take that. Yet it appears that this will be a happy marriage, so long as the two families let go of their prejudices and really meet in the middle. Many in attendance were clearly open to the experience, welcoming the blending of styles.

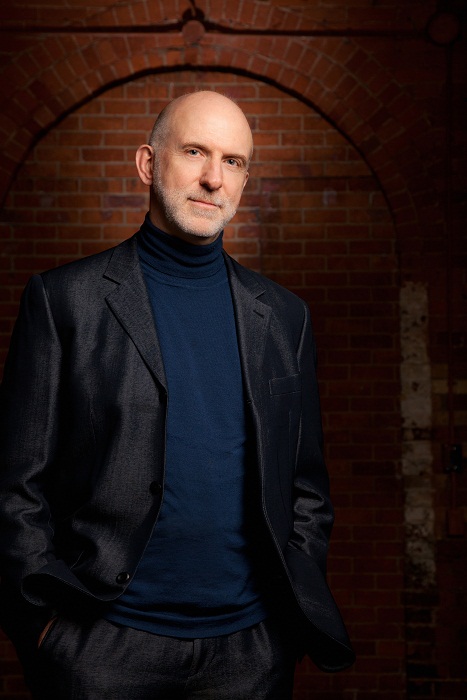

Canadian Stage’s Matthew Jocelyn

As I’ve observed many times over the past few years, Matthew Jocelyn has dedicated himself & his company to inter-disciplinary explorations. The program says “All But Gone by Samuel Beckett, then “a new adaptation by Jennifer Tarver”.

Director & adapter Jennifer Tarver of Necessary Angel Theatre Company

They list four Beckett plays (Act Without Words I & II, Play and Ohio Impromptu). The next two lines say “Featuring Viderunt Omnes by Garrett Sholdice and From the Grammar of Dreams by Kaija Saariaho.” If you come from the musical side you might focus on those featured items, while the Beckett aficionadi would be really intent on the four plays.

I love the fact that I didn’t know what to make of it. For me that’s the element truest to the spirit of Beckett. One of the things I love about him is how open he is (in the sense of Eco’s Opera aperta or “Open Work”), rather than overly determined. These are plays that sit outside the boundary of genres, sometimes invoking laughter, sometimes a darker response. There are many ways that his works can be staged.

I came in a bit fearfully, recalling something Mallarmé had said; when he heard that Debussy had set his “Afternoon of a Faun” to music, the poet more or less said “I thought I already did that”. So too with Beckett, who is already musical in his choice of words. I had thought I was about to see and hear Beckett set to music, which is not at all what this is, thank goodness.

So excuse me if I sound a bit academic for a moment, as I talk about what this hybrid thing is and how it works. When we name it we sometimes help the reception process, but sometimes we strangle it by closing off options or misleading the audience. The dramaturgy question is endlessly fascinating and always useful, I believe.

Tarver’s combination reminds me of several things.

- I could invoke the model of the musical, where the words go as far as they can until music is necessary. I don’t think that’s really what we had this time, but it’s at least a recognizable template.

- I woke up today, again, with Ariodante’s da capo lament “Scherza infida” in my head, a Handel melody that haunts me in the best way. I came into the theatre sensitized to the old baroque dynamic that tends to split the heavy lifting between recitative and aria, between words to advance action or music to express emotion. Opera may have moved to newer means of expression in recent centuries, yet there we were, relying upon those age-old methods. The men were making speeches or performing actions. The women sang, taking us deeper into the irrational realms of emotion that music can make available. The men were distant, cold and opaque while the women were among us and radiant. With this dynamic i couldn’t help feeling that Tarver’s hybrid was attempting to warm up Beckett, make him more human, particularly when i heard the words “jubilate deo”, in the Sholdice composition. Would Beckett have approved? Hm he couldn’t be reached for comment.

- We could speak too of the way theatres or vaudeville would present several attractions, as suggested by Tarver’s use of the word “featuring”, a word that has a very nice resonance for me, and doesn’t imply that one medium is more important than another. I think Brecht, too, would have liked this very well, for the way we were in a very sane & respectful place. All But Gone doesn’t have to be understood as a single work with a through-line and progression, so much as four plays with musical interludes. You find the highlights depending on what appeals to you (and depending also on which family you belong to).

- The eclectic blend of different elements (I am tempted to use the word “pastiche” in the sense of a messy mixture) means that the tonal qualities we get are all over the map, which is only a problem if you show up with stipulations, like that fellow sitting in front of me. The ambiguities of this text are deliciously unresolved, requiring a high tolerance for ambiguity. At times we were in a minimalist place, the unaccompanied music a perfect match for the understated texts in the Beckett.

The main thing is that it works. I’d like to see more such hybrids, to see what can be accomplished in mixing together unlikely ingredients, a worthwhile experiment.