For such a brief title, the opera Canoe invites me to go on at length. It’s not that it is a difficult work, for it was very accessible to the audience at Trinity St. Paul’s. But I want to properly appreciate what I’ve seen and heard. I’m not sure I understand it although I was very moved. I believe it deserves to be presented again, not least because of its depth and richness. I hope there will be some sort of recording.

Opera is a medium that straddles boundaries, a hybrid of words and music with spectacle. How appropriate that Canoe is a product of teams working together across different disciplines, an Unsettled Score production in collaboration with Native Earth Performing Arts, The Toronto Consort and Theatre Passe Muraille.

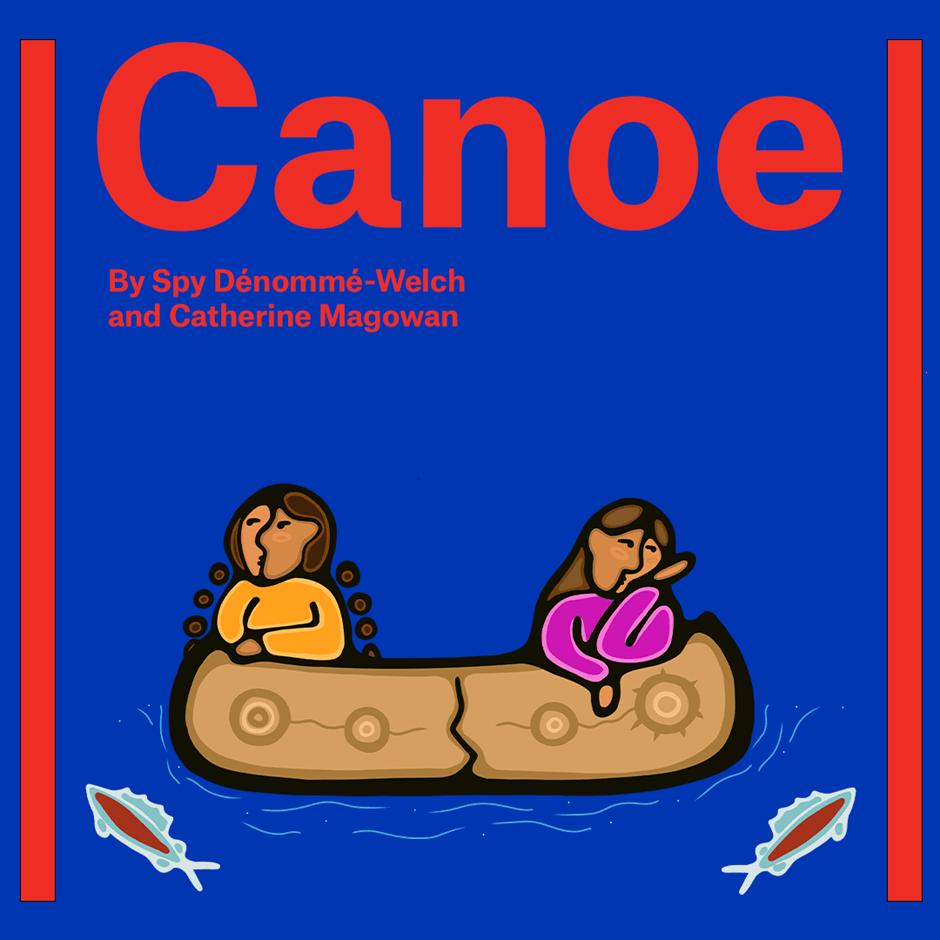

Co-composed by Dr Spy-Denomme-Welch and Catherine Magowan, we are sometimes in the realm of myth, larger than life events that can’t really be shown in a realistic dramaturgy, but only through the combination of words, music and spectacle.

Creation

A great flood.

The program note from Dr Spy-Denomme-Welch, the librettist / storyteller explains the origins of the work.

It’s taken thirteen years to bring this opera to the stage, a long time to carry a work of art. When I first conceived of this opera back in 2009-2010, I imagined telling the story about the creation of the first birch canoe. From there the voices of Tree Spirit, Debaajimod, Gladys and Constance emerged, and so too the complicated and messy worlds they inhabit (both human and non-human).

It’s these elements that make the story of CANOE so compelling and heart wrenching. I wanted to give the work a sense of minimalism, wonder, magic, and imagination while combining new and old forms of artmaking to help tell difficult, relatable human stories, and allow space for the Land to be heard. Ultimately, the story is shaped by a sequence of actions propelled by each of the characters at different points of the opera, all of which collectively activates their transformation.

In these ambitions I feel the team have succeeded admirably, as far as giving the work “a sense of minimalism, wonder, magic, and imagination while combining new and old forms of artmaking to help tell difficult, relatable human stories, and allow space for the Land to be heard.”

A huge story is told in an intimate space at Trinity St. Paul’s. We see mythic events comparable to the Ring Cycle (creation and a flood), yet without the pretension of Wagner, without the weight, without going on for hours and hours. This was playful even while being serious. My perspective may be off, as a person of European Judeo-Christian background, who is comfortable in a church sanctuary that might be a trigger for some, especially in combination with a story touching upon the residential schools.

There’s so much I could say, I want to proceed carefully. I slept on it Saturday and Sunday nights, awake in the night pondering a few things that I don’t fully understand, images that resonate for me in very personal ways. Self harm is terrifying. If I’m off, I hope I can be forgiven as I’m attempting to unpack the wonders of the experience, to share what I felt. I’m a privileged person, so as I was thinking about Residential Schools, the ways in which people become damaged by what they endured, I’m trying to understand but may miss some layers of what’s in this piece. This opera touches upon such things, presented for an audience that included persons like myself, meaning settlers who are trying to understand.

The presentation began with the assurance of support from a social worker if the material was too hard to bear. I recall something similar (that is, the presence of support persons) when I saw Going Home Star, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet piece about residential schools. It’s funny that we don’t offer that for other works. I know people who have issues during the annual noise-fest of the Air Show triggered by the sound of jets, reminding them of war. I know someone who can’t handle war movies because of what they’ve lived through. Perhaps this kind of support should be normalized, and we should re-think our approach to our entertainments, that may be traumatic for some people.

The Idiom of this work is a fascinating mix, at times mythic, at other times presenting average incidents of daily life such as card-playing, eating or dishwashing.

Debaajimod (or Debaaj), played by Michelle Lafferty, is a powerful presence vocally and physically on the stage. They are the one who seems to know what is going to happen or to explain what has happened to everyone else, and sing with an appropriate authority and conviction.

Tree Spirit, portrayed by Conlin Delbaere-Sawchuk, is the title role in a sense as the birch becomes a canoe. That doesn’t mean he ceases to be alive, even if we might think of a canoe (or for that matter, a tree) as an object rather than something that is in some sense alive. The part includes a fair bit of dance, expressive movement.

Gladys and Constance are twin sisters although we also come to know them as brother spirits of the elements both at the beginning (creation) and the apotheosis of the end, when (as the program says) “they are destined to travel the galaxy in their canoe, gathering Star People who have been scattered to bring them back to the Eastern Doorway”. Yet we see them playing cards, eating, arguing, living their lives in a remote forest location.

Gladys (Nicole Joy-Fraser) and Constance (Kristine Dandavino) are very different even if they are twins. The first thing we see is a disagreement, as Gladys cuts down the tree, while Constance expresses regret for this action. Gladys has scars on the arm, reminders of time at residential schools, self-harm. Constance prayed for Gladys, seemingly more loyal to the parents and grand-parents, their stories and heritage, which Gladys mocks as fairytales. But Gladys seems to be in pain.

Throughout the music serves the story-telling and a sophisticated characterization, setting up a vivid contrast between Gladys and Constance that’s sometimes ironic, sometimes very painful to observe. I tossed and turned thinking about this in the night. It’s not surprising that the music has these layers (as though Gladys has distance from the past, singing in a different style) when one recalls that the composition of this work has been underway for over a decade, as its style has been changed, as the creators report in the program. It’s breath-taking in its simplicity, very accomplished writing. At times I thought Nicole approached Gladys almost as a cabaret performer, seeming to resist the operatic illusion by playing with the vocal production, sometimes sounding operatic, sometimes jazzy or like a pop singer. Dandavino in contrast had a more serious operatic sound, even when singing with the utmost softness, coming at the story from the other side. They truly were brilliantly matched in their scenes.

There are unique Canoe textures, such as the very modern usage of the word “whatever”, or swear words, yet alongside these old music instruments to suggest period performance. At times we’re hearing instruments making a very antique sound, the theorbo, the harpsichord, the recorder and strings. Yet at other times the theorbo resembles a modern guitar. Sometimes we were in a mythic place, sometimes we seemed to watch everyday life. Music direction was by Catherine Magowan.

This is the second consecutive show I’ve seen with a tree alive on the stage, although this is perhaps the opposite of what we saw in Crow’s Theatre’s Master Plan, where the tree is the ironic observer and commentator on the events.

Writing in Opera and Drama Richard Wagner observed that while opera had been intended to employ musical means to create a dramatic form, instead it tended to employ dramatic means to create a musical form. The best operas I know touch upon something verging on spirituality in their dense combination of elements that signify so much more than the sum of their parts, a quality I felt more than once watching Canoe for the first time, and which I am certain would resound much more profoundly in seeing the work again. The best works are those we need to see over and over again, deepening our understanding of them. That’s what I would hope for with Canoe.

I hope to see this opera produced again somewhere, and will keep my eyes open for any possible recording, video or audio, so that I can revisit the magic I experienced this past weekend.