The Toronto Symphony’s program for this week is a surprisingly powerful combination.

We open with 17 minutes of passionate singing by mezzo-soprano Emily D’Angelo, seven songs composed by Alban Berg (1885-1935) between 1905 and 1908.

After intermission we settle in for the hour and a quarter of the Fifth Symphony of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) composed in 1901–1903, the last decade of his life.

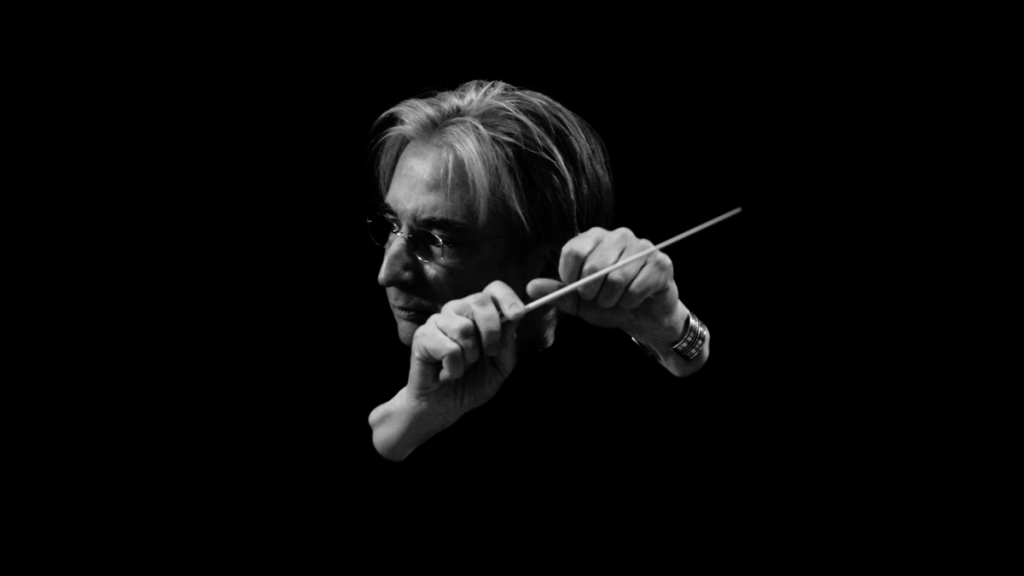

Although Michael Tilson Thomas was to conduct I gather he had to cancel due to his ongoing health concerns, alas.

Guest conductor David Robertson made his TSO debut. I didn’t know him or his work but after seeing him last night I was very impressed. In the songs David was as self-effacing as an accompanist, a word that we rarely hear anymore even if those of us of a certain vintage still recall the concept, perhaps best captured in the title to Gerald Moore’s memoir “Am I too loud?” When we came to the Mahler Symphony we saw a different side to him.

Let me speak first of the songs, a version of a pattern the TSO regularly follow, where they put something more challenging to begin with a crowd pleaser afterwards. What’s different this week is that the opener was not just spectacular but in every way the peer of the popular piece that followed. I believe the verdict on Berg’s songs is shifting with time, as programmers stop worrying about how the works fit with the rest of the composer’s output. Who cares what Berg was to become if he could write such spectacular music at this point in his career? It’s a bit mind-boggling that Berg could compose this way in his early 20s (although they were not orchestrated by Berg until much later) the songs showing another less dissonant side to a composer associated with atonality through a pair of operas Wozzeck (1925) and Lulu (unfinished at the time of Berg’s death in 1935).

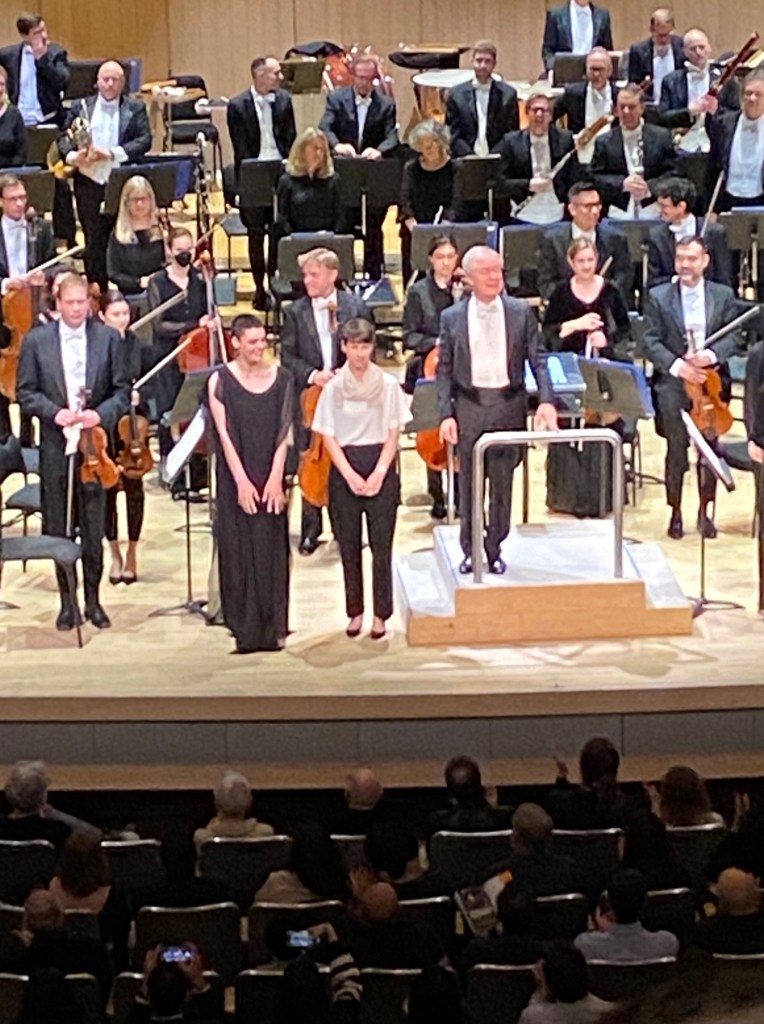

I’ve had the pleasure of watching and hearing Emily before, a standout in Canadian Opera Company productions of Cosi fan tutte in 2019 and Barber of Seville in 2020. I couldn’t resist listening to her sing Berg songs on YouTube, where their treacherous ambiguities lead some other singers astray. Let’s just say that the best versions you will find are by this brilliant young Canadian, and last night she was again spectacular.

I have one small quibble, but it’s not with Emily. I wish that when we’re watching a hybrid work for music with text such as this one at Roy Thomson Hall , that we would have the titles projected with a translation. Sorry if I sound demanding. As Emily started, I saw heads going into the program to figure out what we were hearing. Even a printed text of the songs would be better than nothing. Would you expect to see a foreign film at TIFF without subtitles? Every little opera company in the area (Opera by request, Voicebox, and others I could mention) let alone the COC and Opera Atelier give us translations. How could it be otherwise, when we are listening to singers interpreting words in another language? While Berg does offer us nice music to go with the Mahler, we insult Emily when we are unable to understand the nuances of her splendid singing, even if we did scream our approval.

There was an encore that wasn’t in the program. I asked Cecilia Livingston through social media. She was brought up onto the stage for applause after Emily sang the song: a Clara Schumann lied of the poem “Lorelei” (presumably Heine, although I could be wrong), in an original arrangement by Livingston getting its TSO premiere (I mistakenly said “Canadian premiere” but Cecilia tells me that was with the NACO, as I badly paraphrased what Emily said announcing her encore). Again, I wish I had the text before me as I watched Emily’s urgent performance. While we’ve twice seen her in comedy in the two COC shows I mentioned above her intensity in this serious repertoire was hair-raising.

I wonder if there’s anything she can’t sing.

And so we went from the gently supportive work by David in the Berg songs, to something entirely different for the Mahler. There was something to give me genuine shivers running down my spine in every movement. I say that as a devoted lover of this piece. The opening movement fanfares lead us to a softer than usual reading of the string responses, gradually building to some tremendous climaxes. The second movement was urgently spine-tingling, as David seemed to stir up something in the ensemble. The TSO respond to him, playing crisply. As a fan of quicker Mahler I’m grateful how powerfully David urged the orchestra on.

We paused before the third movement as horn player Neil Deland took up a position to properly foreground what was to come, his powerful solo work. I’ve heard this symphony all my life, but never seen it done with such a sense of poignant drama. Mahler was a man of the theatre, writing flamboyant moments, ironic passages apt for satyrs or satire (if they’re not the same thing) just waiting for an ensemble to properly seize the moment and take the stage. After allowing Neil to return to his usual seat, giving us another ostentatious pause (useful also in delineating Mahler’s structure dividing the symphony into parts 1, 2 and 3), we were into the gentle Adagietto, which may begin softly but does find its way to its own sort of climaxes. I find it mildly irritating that the part of this symphony that seems to be most popular is the movement that I believe was designed to give the wind players a rest, the soft Adagietto fourth movement. It’s a bit like thinking that the Grave Digger is the most important character in Hamlet, charming as his appearance may be. The Adagietto is that delightful piece of baguette to clean your palate between spicy courses that might otherwise overwhelm you. Of course for those who find Mahler too rich and prefer some Vivaldi the Adagietto is a gentle oasis, a lifeline when you’re drowning in big sounds. I grew up on big sounds so pardon me.

And without pause (observing the composer’s division into three parts rather than five) we were into a more restrained and controlled reading of the finale, one that built up gradually to the silliness of the last phrase. As in Shakespeare, comedy was always lurking.

Athletic? Agile? I’m impressed that David was able to turn his head to face any section of the orchestra while keeping his body aligned in the middle, his feet still square to the podium even as he turns wherever he needs to turn. The last conductor I saw with this kind of flamboyant response to the music was Leonard Bernstein, except David manages to do it without any of the overdone showmanship, working in support even when the orchestra was triple forte. He has the clearest beat I think I’ve ever seen. When the symphony was over David dutifully went about the orchestra congratulating each section, drawing applause. He was like a servant, or maybe a teacher caring for his pupils. But the bond seemed genuine.

I hope the TSO bring him back, he’s a great artist and a lovely man.

The TSO repeat this concert Friday & Saturday night. If you can make it you really should go!

Excellent review, Leslie! Makes me wish I was there.

I was delighted to see that this mid-week concert was full, looking close to sold-out, and deservedly. Thanks for the kind words.