The reason I interviewed Adam Klein is interest: in his career, his opinions, and anything I might learn. I am a fan.

Adam sang in the Lepage Ring, has been in a lot of shows at the Metropolitan Opera and elsewhere.

If you search the Met Opera database you see 94 entries for Adam Klein. Here’s the link. For each one you then click on the opera to drill down for details such as cast and the conductor:

https://archives.metopera.org/MetOperaSearch/search.jsp?q=%22Adam%20Klein%22&src=browser

There’s an error of sorts. The database reports Adam’s debut Wednesday January 19, 1972 as Yniold, playing the little boy in Pelléas et Mélisande, as discussed in part one of our interview.

But seven Pelléases and four Zauberflötes (second boy) later: what’s this?

Adam is again reported making his debut but this time as an adult almost 30 years later in 2001 in Arabella. Maybe other singers have accomplished this feat, but were missed because the database didn’t connect adult and child performances, separated by so many years.

His latest entry is Sat, October 31, 2015 in Tannhaüser.

The 94 Met performances are comprised of

-seven Yniolds, including the debut of Louis Quilico (Pelléas)

-four Zweiter Knabe (Zauberflöte)

-six Count Elemers (Arabella)

-one Steva (Jenufa)

-one Chevalier de la Force (Dialogues des Carmélites)

-seven Japanese Envoys (Le Rossignol),

-thirteen Chekalinskys (Queen of Spades)

-fifteen Jews (Salome),

-one Witch (Hansel & Gretel)

-two Iskras (Mazeppa),

-eight Fyodors (War & Peace)

-seven Drunken Prisoners (From the House of the Dead) ,

-thirteen Yaryzhkins (The Nose),

-two Loges (Das Rheingold),

-seven Heinrichs (Tannhaüser)

I wish I could see / hear Adam sing in Toronto. He’d be an ideal Parsifal. But in the meantime I had lots more questions. Here is the rest of our interview.

~~~~~~~

Barczablog: Looking back on the roles you sang at the Met, what was your favourite and what was the hardest?

What was my favourite: that would be Yaryshkin in THE NOSE.

My other favourite Met gig was covering Gandhi.

What was the hardest: that would probably be Aron in MOSES UND ARON — I say that because I covered it twice and had to completely re-learn it for the second one.

Barczablog: Who was the director whose work impressed you most, and you’d like to work with again?

Adam Klein: Ooooh, good question. The first name that pops in is someone who does things with opera that are different but also work: Phelim McDermott, who directed the Met’s SATYAGRAHA in which I covered Gandhi twice, but also co-directed Spoleto USA’s THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL by Helmut Lachenmann in which I was the first person besides the composer to portray Leonardo da Vinci – thanks to John Kennedy basically picking me for the part – but Phelim okayed that choice quickly, remembering me from SATYAGRAHA.

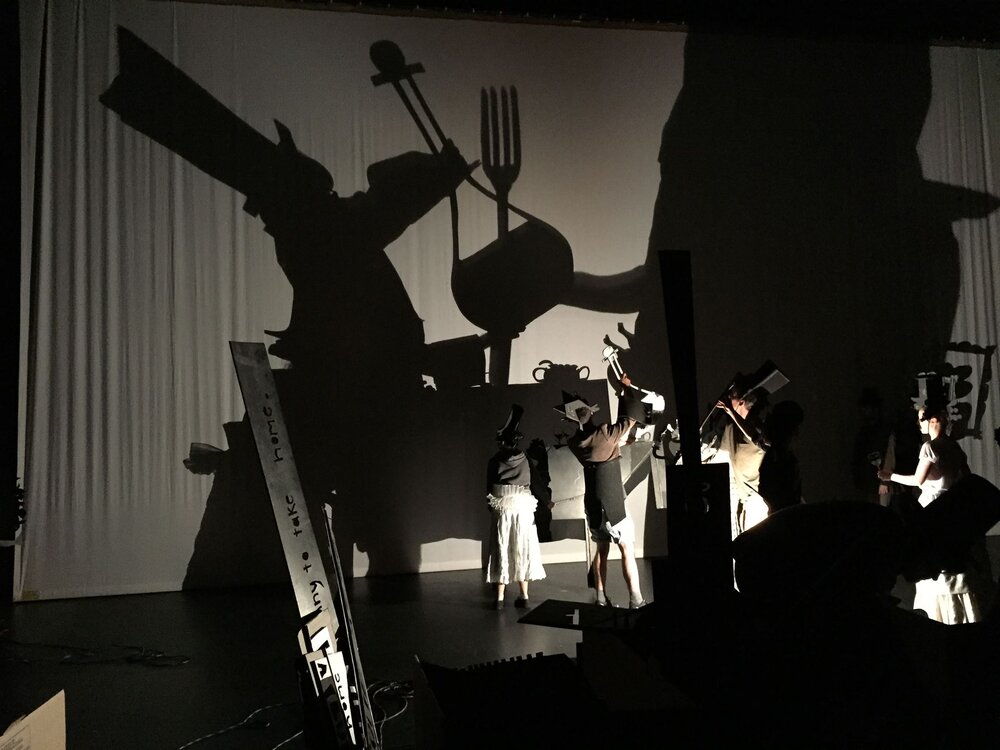

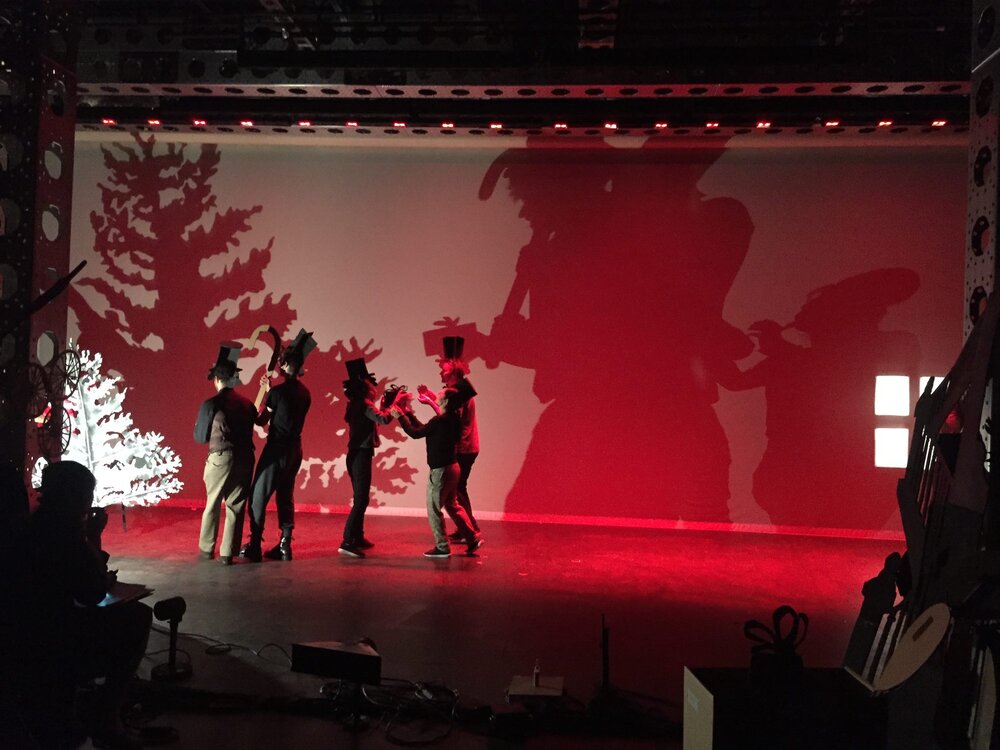

This all sounds like I like Phelim because he liked me, me me me, but that’s not my intent. Regardless of who played Leonardo – and Phelim had no control over the SATYAGRAHA casting to my knowledge – that LITTLE MATCH GIRL would have been one of the coolest productions ever, anywhere. Ten actors/puppeteers and me providing the stage visuals (and there were visuals of the huge orchestra and chorus because they surrounded the audience): Phelim and co-director Mark Down, with their hand-picked actors and me, developed a visual language using a sort of extended shadow puppetry which, like what Phelim and his troupe did with Satyagraha, perfectly complemented the music, which itself perfectly complemented the heartbreaking Hans Christian Andersen story, or at least Lachenmann’s reading of it, with a German translation of something written by Leonardo thrown into the middle, and that’s where I came in.

Adam delivered texts from the notebook of Leonardo da Vinci in translation.

Barczablog: This is again reminding me of your theatrical flair. If you lost your voice (horrible thought) you would still have a lot to offer as an actor. I wonder (just like the old song says):

“You outta be in pictures“. While you’re very musical you really get theatre and drama.

Adam Klein: We not only developed this visual language in the most collaborative endeavor between directors and players I’ve ever been part of: we also spent about two weeks doing creative/acting/movement exercises and question-sessions in order just to get to what we wanted to say, in this story, with this language. Some performers prefer the preparation process to the performances: if the process in every opera could be like this piece was, I would be one of those people. And I don’t say that for me the process trumped the performances because each night a score of the aging Charleston audience that came in expecting the music from the Disney film would get up and walk out on all fours once they realized there was no intermission. I say it because once the rehearsal process is over, we have to try and repeat what we’ve come up with for every performance, and though performing the show was fun, it was nothing compared to how much I enjoyed the journey we took to get there. So often in opera, you show up for the first rehearsal to learn that one of your cast-mates, or the director, or the conductor, is in it for themself and not interested in collaboration, in this art form that’s supposed to be the ultimate synthesis of all art forms and therefore has the potential to be the ultimate collaboration experience in order to let the piece grow to its full potential. Most of the time, opera falls short of what I think should be a given; that time in Spoleto, we got there.

Now I mention co-director Mark Down, whom as I understand it Phelim brought in to the project, though I don’t remember why he thought two directors would be better: it might be because Mark had a lot of experience with shadow puppetry; I don’t think it’s because quite a few of the actors were in Mark’s troupe. Anyway, though we were all present at rehearsals, I don’t know what was discussed between Phelim and Mark outside rehearsals, and so I don’t know just how much of MATCH GIRL was Phelim’s, how much was Mark’s and how much was us actors’.

So I want to give Mark a tentative co-first-place for this question, even though Phelim did have ultimate authority. Except for a very few decisions, the production just wasn’t run in an authoritarian way.

I also have to give a close second place to William Kentridge for his NOSE which I got to be in at the Met.

This was the other example in my career of a perfect marriage between story (Gogol), music (Shostakovich) and visuals (Kentridge) which made it such a hit that first season, after years of Eurotrash murders of classic shows, many of which I was in, and premieres of shows that don’t hold a candle to the Nose. Circumstances were slightly similar to the Phelim-verse: we spent a week developing a physical language that all the cast (a very large cast) could use, to give the piece homogeneity in that way. Unfortunately, some of the opera singers weren’t on board with this process and spent rehearsal time just jawing about opera-unrelated subjects instead of helping this piece be as successful as possible, or at least keeping quiet. Also similar was Kentridge’s bringing in of Luc de Wit as co-director, to handle this physical language – because Kentridge the visual artist knew that wasn’t his forte.

I discovered something about Met broadcasts during NOSE, though. Over the speaker in the Green Room we were treated to a rehearsal of the pre-show dialog that, during the actual show, would feature Mr. Gelb being interviewed about the production. The rehearsal was with someone else whom I don’t know, doubtless involved with the broadcast side of things, reading the questions, and someone else reading Gelb’s answers. What do you know, come broadcast time, in the “live” interview, Gelb gave the same, verbatim, answers to those very questions, which means the whole thing was scripted. So why they didn’t just record the interview and have done with it, I don’t know. That would seem safer.

Barczablog: Maybe it’s like our interview process. I’m always trying to make these interviews seem life-like even though you see the questions and reply through email or Facebook Messenger. It seems everything is becoming virtual.

Adam Klein: Hmm. Maybe.

A very close third on my list would be not an opera but Mahler’s 8th Symphony with the Boston Philharmonic under Benjamin Zander no titular Director other than him the conductor. That experience was so good, not because Zander was a great director, though mind you he was an excellent conductor (and by that I mean his physical technique was easy for a singer to follow and flexible enough to follow the singer when necessary; AND his ideas about the piece were spot on and he communicated them well to singers and orchestra): but because he hand-picked the solo singers, who to a person were both able and willing to do exactly what Mahler asks us to do in the score.

Barczablog: I’ve inserted this little video excerpt to contextualize what Adam is saying. When Benjamin Zander picks you it’s not some random event as this video shows.

That includes pianissimo high notes from the dramatic soprano as well as everyone else. I had previously done an Eighth with another group, and some of those soloists were your standard opera singer: yes, Maestro, yes, Maestro, then come performance you just sing as you please, composer be damned. Well, not Ellen Chickering. And not me. And not the rest of us. Our pianissimo ensembles were actually pianissimo, which made the loud sections all the better by contrast. One example: when the tenor solo first sings in the “Faust” section, the instructions are that he is not to stick out as a soloist while the chorus women are describing him, until a certain point where he does arrive at the front of the texture. If the audience doesn’t understand why they can’t hear the tenor up to that point except as part of the accompaniment to the women, that’s because the program writer and/or pre-concert lecturer didn’t do their jobs: it’s what Mahler wanted, and it’s up to the producers to educate their listeners to what Mahler wanted BEFORE the concert. Of course, the producers themselves have to understand Mahler to start with, and not just program it because they know it’s popular, particularly the Eighth. It is, in my opinion, the closest Mahler got to writing an opera, Das Lied von der Erde notwithstanding.

Anyway, I count that production of Mahler’s Eighth in the top five of my classical music career experiences. (And it bears repeating that opera singers don’t just sing opera.) The other two to round out the five, as it were, are both Spoleto productions: Pascal Dusapin’s FAUSTUS, THE LAST NIGHT, conductor John Kennedy, director Davide Herskovits – totally cool on every level; and Giddens & Abels’s OMAR, conductor John Kennedy, director Kaneza Schaal. Visually AMAZING, excellent libretto, so-not-out-of-the-mold music, perfect prosody.

Actually it doesn’t come first on my list only because MATCH GIRL was just that much cooler, though I think OMAR is a more important piece. I think I’ve said that to you before: in my opinion it’s the greatest American opera of the last hundred years, if not three hundred, even if I don’t recuse myself regarding my own opera LEITHIAN, which has never had a full production, simply because my opera is taken verbatim from the Tolkien because I didn’t think I could or should try to improve the plot, whereas with OMAR Rhiannon had to fill in a lot of gaps in the story to make it the vibrant piece of theater it is.

Barczablog: We’ve talked about agism & lookism and the evolution of opera singers. How do you see opera changing since the advent of High Definition broadcasts?

Adam Klein: I don’t see anything good coming out of the Met HD system, what I call Hollywood on Amsterdam Avenue. First, Gelb’s negative opinion of opera and classical music is well known, so his motivation to turn opera into film must be wondered at. Next: Opera, once again, is a synthesis of many art forms, so if you’re going to layer the art of filmmaking on top of it, you should be able to make it even more amazing than it was before. Nothing about the filming of the shows at the Met does anything to enhance the operatic experience. I could cite many examples but I’ll list just a few. To start with, generally, broadcasting opera favors the smaller voices, and worse, it disfavors the larger ones, because the close body mikes they use simply can’t handle the decibel level, upwards of 110 in many cases; and it equalizes small and large voices, removing the amazement we feel, when in the physical space, that a human unamplified could be making that much sound, and it’s still pretty.

In fact, the mikes often make us sound ugly: Callas is the premiere example. You listen to the live back-of-the-hall recordings of her and compare them to the close-miked studio mixes: I thought her voice was just not pretty until I heard that field recording of LUCIA where she was soaring over everything, and only then did I understand why she was so revered for her voice and not just her acting.

Okay, at the Met it’s not even mikes in the footlights anymore, which gave the big voices a chance while still favoring proximity to the lip of the stage. It’s body-mikes just like they use on Broadway. That’s what makes it possible to cast someone like Terfel, who himself said he was no Wotan, to star in Le Cirque des Nibelungen. I don’t think Gelb et al are totally responsible for this: the recording industry for decades has played with levels: Bjoerling and Nilsson in TURANDOT, for instance.

Barczablog: Yes of course. I’ve always loved that recording, first encountered it as a kid, and come to think of it, it’s a bit of a travesty…You’re right. I suppose that too is a kind of virtual opera.

Adam Klein: His voice was tiny compared to hers, and on the recording you can tell that he’s one foot from the mike and she’s at least eight feet away if not more. It sounds ridiculous, whereas Corelli and Nilsson were matched for volume, for which I relate a first-hand report from my father Howard who reviewed operas for the New York Times in the early 60s and got to hear Nilsson & Corelli live together at the Met. As he described it, there was nothing like hearing the two of them going at it in the duets and reverberating around that hall: finally Nilsson had someone to share the stage with, in terms of vocal prowess. Now, it is LITERALLY IMPOSSIBLE to reproduce such a thing on an HD broadcast. The audience member is at the mercy of: the speaker system in the movie theater; the quality of the mikes on the performers; the fingers of the sound technician playing with levels on the mixing board; the prerogatives of the impresario choosing singers who may look more the part on screen, in his/her opinion, regardless of whether they can or should sing the role.

And that’s just the aural aspect of opera, which is also an acting medium, so you should get the visuals right. They do NOT.

Two examples:

In SATYAGRAHA, a large part of the impact of the piece in the theater is the static quality that the so-called minimalist music sets up. (I’ll save my opinions on true minimalism for another time.) Twenty minutes of basically the same music, building ever so slowly, is the general pattern. Big chorus numbers with Phelim choreographing the great Met chorus as best he can while still letting them read the words off the monitors at the back (because it was decided there was no way they’d be able to memorize the Sanskrit, supposedly). If any opera could benefit from what I call the slide-show treatment, it’s this one, because it’s a kind of musical slide show to start with. But static music with static staging requires what to keep the director’s intent when translated to film? Anyone? Watch how David Lynch films things: he calls them “moving paintings”, but often he just sits on a locked-off shot, forcing the viewer to look around the image instead of trying to follow one moving subject, which forces the viewer to notice things she wouldn’t otherwise have seen. This is what this type of minimalist music does with our ears: we get used to the pattern, and suddenly things jump out at us that we wouldn’t have noticed in a one-time-through situation. And this effect can’t be ignored when you stage such a piece, and Phelim didn’t ignore it. BUT. The person at the video mixing console in the semi-trailer on Amsterdam Avenue DID ignore it. What would have worked as a static shot with maybe a few judicious cuts to other angles became an endless series of pans and zooms which not only dissipated the visual impact of what was going on on stage, but also had nothing to do with the timing of anything in the music. It’s as if a D. O. P. (Director of Photography) and camera crew from the NFL broadcast world were contracted to come film an opera. Without doing any musical homework. Sorry, but it’s not the same.

Example The Second. In THE NOSE, because of the proximity of the new Lincoln Center movie theater, between rehearsals of something else I got to watch myself in one of the re-broadcasts, to see what they did with Kentridge’s visual tour de force. Oh, guess what. Pans and zooms. Pans and zooms. Nothing to do with who’s on stage or where they are. Wait! Did they cut to a shot of someone not singing at all, right in the middle of one of Paolo Szot’s high notes??? Yes they did! There, they did it again, this time to James Courtney in his ONE SOLO. I guess they got bored. Wait, did they pull back to get the wide-angle shot of all Kentridge’s drawings and words flying everywhere and then out of the main playing area onto the walls?? No they didn’t! This last all the more surprising since Mr. Gelb crowed to me personally about exactly that, early on in Tech Week. But either he didn’t tell Mr. NFL D.O.P. to be sure to include that, or D. O. P. ignored him.

Now, those people paying good money to sit in a movie theater in West Podunk, North America: do they know that what they’re seeing is so different to what they’d see if they could afford to go to New York to see it live? No they don’t, because the Marketing wing has told them (I’ve seen the brochures) that the Met is the best opera company in the world, showing the best singers in the world, in the best productions in the world, and Jane Q. Public has no way to independently verify these assertions – none of which are true, at least not all the time and in my opinion not most of the time. Of course, ALL of this is my opinion.

Lookism: When Gelb took over at the Met, he declared No More Stage Makeup. It Doesn’t Look Good On Screen. With the result that for most of the productions I was in after he showed up, I didn’t even get BASE makeup. Yet the harsh stage lights remained the same, so we all got washed out, except on the Silver Screen where we look “nice and natural.” Sorry, no sale.

Barczablog: Parenthetical observation of the ironies of it all.

My first impression of Lepage’s Ring (naive believer that I was and maybe still am) was that the objective with that set, combined with the High Definition broadcasts was in a sense to give us something in the cineplex that was as good as what you see when you come to Lincoln Centre. It was one of the motivators that inspired me to see the show in NY and having seen it, I didn’t lose that impression, that Lepage’s set seemed to set up a relationship with the camera that was superior to what you could get in the house except in the very best seats. It reminded me of what we learn in theatre history about the stage of Serlio in the Renaissance, that would give the prince the perfect perspective, while everyone else was in a sense envious of the prince’s view. Of course that’s turned upside down if the expensive seats in the theatre aren’t as good as the ones we get in the Cineplex, but that’s how it felt when I saw it. The ideal seemed to be the broadcast version not the live version (and the policy you’ve reported on makeup seems to support this, right?).

Don’t laugh but I saw that Gelb might be a visionary, if this was what he asked of Lepage (ha okay maybe not). But I guess that was merely (excuse the pun) my projection. I can’t help but wonder if there was ever any discussion about this, as a possible objective for the set in the theatre.

AND I also can’t help wondering whether Lepage actually meant to do something much more elaborate as far as the puppets and ubermarionettes. There you and the Rhinemaidens were, on wires, and we don’t see that again other than Lepage’s gorgeous Grane (the horse) in the last opera. Did he have something else in mind, what with all that expense?

Just as I am a fan of Adam Klein, I am a fan of Robert Lepage.

Excuse me for interrupting…. back to Lookism.

Adam Klein: Lookism: Before Gelb took over, we were at a party for one of the shows I was covering and one of the Artistic Liaisons told us they needed to do something to bolster the subscription base because, and I quote, “Our audience is literally dying.” So no matter who replaced Volpe, they had to try something. But when that new production of ONEGIN came out, I saw from my commuter-bicycle the huge photos of the two leads in a steamy embrace, loudly plastered on the sides of the NYC buses. It was as if they were telling us that the voices don’t matter anymore, the music doesn’t matter anymore, the sets and costumes don’t matter anymore: what people come to an opera to see is exactly what they can already see on Spanish telenovelas. Or soap operas. Oh. I get it. Soap OPERAS. Well maybe that’s what the Intended Demographic wants to see on the second or third most famous opera stage in the world (after La Scala and Bayreuth), but that’s not what I would pay for. And then when sales continue to decline, it gets blamed on the SINGERS AND INSTRUMENTALISTS. Some of that made it into the media during the strike threat and mediation.

Rule #1: The chief magic of opera is in the voice. As much as I am interested in elevating the acting side up to where the sets, costumes, instrumentalists and voices already are or should be, without the amazing sound of an operatic voice, the rest is nothing. We can’t lose sight of that when translating this particular form of live theater to a two-dimensional screen with two-dimensional sound. (Unless they’re doing quadraphonic speaker systems for opera now like they’ve been doing for blockbuster sci-fi films for decades now: since I don’t attend opera in movie theaters I’m not aware if they have or not.) So should opera telecasts only be HD-streamed in 3D quadraphonic format? Wait, 3D IMAX quadraphonic format. YES. To start. That would be closer. Then we’ll see. But keep live opera on a physical stage while you’re at it, please. There’s nothing like it.

I’m a big advocate for bringing the greatness of opera out of the ivory tower executive suite down to the Person On The Street. I hear that in Italy for centuries opera has been the theater of The People, but in the US it’s still the theater of the Privileged, while Broadway is OUR theater of the People. (However, tickets to the big Broadway shows are as exorbitant as they are at the Met.)

People have tried producing operas in a Broadway setting only to discover that, mikes or not, you need Classical training for the stamina required to sing even a Puccini opera; why aren’t more opera companies doing productions of at least the classic Broadway shows which were written for singers with technique? My teacher Walter Cassel sang Wotan AND Billy Bigelow. Unmiked. I get the impression that those in control of opera are not doing a good job selling its strong points, its uniqueness, to the general public; meanwhile, essential funding from government entities continues to dwindle in this age of increasing conservatism bordering on totalitarianism, with the result that your local mom & pop opera company is struggling to survive while people think they can get their proper dose of opera by going to their local AMC or Cineplex or Cineworld. It may not even be possible to fight the big publicity machine trying to turn this venerable live theater form into a subset of the film world; yet companies like Taconic Opera, Utopia Opera and Harrisburg Opera Association continue to innovate and mount well-received, well-attended productions on shoestring budgets; and while that endures, the True Spirit of Opera will continue to have a presence on this planet.

As far as agism goes, that didn’t start with HD streaming and it won’t end in opera or the film world (or any world it’s a part of) unless the “intended demographic” comes to include people in their 40s, 50, 60s, 70s and 80s. Wait! Isn’t that the exact age of operagoers?? Yes it is!! So why do impresarios continue to cast twentysomethings who can’t sing what we veterans can sing? I don’t know: why did Mildred cut off the ends of the roast to cook it, like her mother and grandmother did? (Grandma enlightens us: “My roasting pot wasn’t long enough and I had to cut the roast to fit inside it.” This isn’t as tangential as it may seem: in a remount of a Richard Jones production of QUEEN OF SPADES in San Francisco, I as Chekalinsky was dressed in a fat suit. When at the final dress I asked the designer why the fat suit, his answer was: “Well in the original production, the tenor singing Chekalinsky was quite fat, and we decided to keep the look.”) They do it under the mistaken dogma that Youth Always Sells, which ignores Rule #1 of Opera: The Voice Comes First. (The exception to both of these is: Star Status Trumps Everything.)

So if HD streaming, and let’s be clear, several big companies are doing it, is demoting Rule #1 down the list in favor of film-style visuals, which aren’t being done well anyway, it is certainly not changing opera for the better. The bigger pity is that it doesn’t need to be this way. You want opera on film? Then stage it for film! Get the film people from Marvel or Harry Potter, who understand the power inherent in the unity between music and footage, to cut it right! Don’t film it in an opera house, do it on a bluescreen set! You’re already spending all this money, you might as well do it right.

Barczablog: Talk about the way American companies cast opera and perhaps reflect on what you saw in Canada. We have more govt funding you have more private donors: but does it feel ultimately like the same set of problems, Europeans condescending to us.

Adam Klein: I don’t know if Europeans condescend to North Americans, but enough Eurotrash productions get here to show that we look up to them. We don’t need to.

Barczablog: Thank you for saying that!

Adam Klein: Casting opera: I’ve already touched on this in the answer about HD, but I can write specifically about the regional houses in the US and Canada. In the US I’ve worked in: NYC, Boston, Chicago, Portland ME, Portland OR, El Paso, Fort Worth, Dallas, Seattle, Central City, Indianapolis, Memphis, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Buffalo, San Francisco, Atlanta, Charleston SC, Charleston WV, Norfolk VA, Nashville, Durham, Harrisburg, Pittsburg, Philadelphia, Wilmington DE, Hartford CT, Yorktown NY, and many other smaller companies; in Canada: Edmonton thrice, Winnipeg twice, Regina and Toronto once each.

To start with, the visa problem alone keeps many regional houses from even thinking of hiring from outside our respective borders. The pandemic made it worse. The U.S.’s a-hole behavior after Nine Eleven made it worse.

I got into the Canadian scene as a replacement for a tenor who didn’t show up for RIGOLETTO in Regina, and I happened to be free. Irving Guttman ran that company at the time, as well as the ones in Edmonton, Winnipeg and Vancouver. From that one gig as The Duke I got five other jobs: as Edgardo in Lucia in Edmonton and the leads in Bohème and Butterfly in Edmonton and Winnipeg. So I never auditioned for any of those jobs.

I did audition, in New York City, for COC when Richard Bradshaw was there, and eventually got the one gig covering Mime in their new RING cycle in the new theater. Bradshaw told me that the reports he heard about my work were good, so I was optimistic about more engagements in lovely Toronto; but then he passed away, and so did my name in the ears of the Powers that be.

Barczablog: Sigh, another reason (not the only one) to lament Richard’s passing.

Adam Klein: When Irving Guttman retired from all his Western companies, that was the end of my career there as well. So I’m afraid that doesn’t shed much light on Canadian opera casting as far as my work goes, but I can report that most if not all my colleagues on the stage in my Prairie Province Gigs were Canadians, from all over; we even had a Newfie who described herself to me as crazy, perhaps anticipating what I might hear about Newfies while in Canada. She wasn’t any crazier than I was. (hmm, maybe there’s a reason I love folk music from Newfoundland…)

At all these jobs I never felt singled out for not being Canadian, or yes being American, which aren’t exactly the same thing; and I really miss those times (plus you can rent curling ice by the hour in all the big cities, whereas in the states most big cities STILL don’t have curling facilities, at all, and those that do (DC for example) are run by clubs that you have to belong to in order to play unless you bring your rink to a spiel. Imagine how bowling alleys would do if that were the case.). I should also point out that these Canadian singers were just as good as the Americans I worked with in all the American houses; and in Canada, an opera singer is an ACTOR and therefore a member of Canadian Actors’ Equity Association (CAEA), so for instance I got to work with a guy Torin Chiles who was an extra in a Jean-Claude Van Damme film. That doesn’t happen in the States, where opera singers are NOT actors, they’re “musical artists” and members of American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA). So in the States, where AGMA operates that is, which doesn’t include most of the regional houses, we don’t get the same benefits as members of Actors’ Equity or SAG-AFTRA or CAEA.

Okay, why did I mention curling?? I discovered it because of opera in Canada. Squash as well.

All right, now the question of casting in US opera companies. This has CHANGED. Back in the 80s and 90s and the early 00s, the model was this: an opera company books time at one of the many NYC venues that work for such a thing, and sends out feelers to agencies that it works with, to send singers to audition for this or that role, or it’s an open call to everyone, so they can cast for several seasons at once. The singers contacted by their agents to attend the audition must engage and pay their own accompanist; that plus any coaching they might pay for to prepare their arias, and whatever travel arrangements they must make, is the singers’ only expense. Since so many singers have moved to the NYC area specifically because it’s the Opera Audition Mecca, travel outlay only really affects out-of-towners. The opera company foots the bill for their own travel, lodging, and booking the audition space. My audition for COC was a big rehearsal room in Juilliard’s Rose Building.

NOW there’s an entity called NYIOP, for New York International Opera Auditions, which works like this: NYIOP sends out a blanket email to every singer on their list, announcing upcoming auditions, which will cost each singer several hundred dollars to participate in, and they still have to bring their own accompanist, and pay for travel if need be. Meanwhile the opera companies show up on a free ride: NYIOP takes the singers’ money and pays for the impresarios’ everything. This of course favors rich singers or singers with rich obliging parents. Also, though NYIOP lists which companies will attend and what shows they’re casting for, the impresarios are under no obligation to show up. For example, in my last (and I mean it was my last) audition for NYIOP, a Polish opera company was slated – GUARANTEED – to attend, so I prepared an aria from a Polish opera specifically for that impresario, because I’d studied the Polish language for years and would love to work in Poland. I showed up for my time slot, with my accompanist, and started with the aria from HALKA. Those who were there limply asked for a second number, which I sang. Not only did I get no job (and this was the last of more than a dozen NYIOP auditions I sang at, none getting me any jobs), but I found out, AFTER I sang, that the Polish impresario had not shown up. So, hours and hours wasted memorizing an aria I’ll never use anywhere in the States, and money again wasted paying NYIOP so they could pay travel & expenses for those impresarios who did show up – and make a profit for NYIOP as well, of course. If an opera company makes and pays for its own arrangements to set up auditions, they will send SOMEONE to listen to us. If We Singers, who are the Inexhaustible Wellspring on which All Opera is funded, just like the Middle and Lower Classes are the Inexhaustible Wellspring on which the U.S. Economy is founded (get it? Funded – Founded. I’m here all night.), foot the bill for the travel, lodging and audition venue, Mr or Ms Impresario can show up or not, no biggie. It’s all good.

Whatever.

But there is a commonality between these systems. The voice. An opera audition is not an acting audition. We might almost do it like they audition players for symphony gigs: behind a baffle. All they really want is for us to stand there and sing at them. But I don’t want to imply that they’re only listening to our voices, because many if not most of them listen at least as much if not more with their eyes as their ears – so the black baffle wouldn’t work. (Or it would force them to use their ears.) But it all depends on the impresario. My wife Tami Swartz, when casting for Harrisburg Opera Association, looks at the complete performer; can she sing, can she act, will she arrive prepared, can she play well with others? Not irrelevant but certainly secondary is how she looks. But we have a baritone friend who at a gig in the US walked into the office of the impresario, who was moving headshots around on the floor, mixing and matching them in order to come up with a cast for La Bohème.

Barczablog: Ha, weren’t we just talking about the impact of the high-def broadcasts? If it’s understood like a film (with its visual impact) that makes total sense. But yes it’s crazy.

Adam Klein: Who auditions us? Not the conductor or stage director, unless that’s the same person as the Executive Director or Music Director. Sometimes the Exec’s right-hand person: Tami and I drove a thousand miles (1600 km) to audition for a regional opera house exec, whom I knew from a previous gig, only to end up singing for an underling of his. No explanation.

Once you get a gig somewhere, if you behave well and perform well enough, you have a chance to be asked back: hence my 5 Prairie gigs after my sub job in Regina. But then comes Regime Change, which never takes into account which performers the local audience liked the best, but always brings in Those The Impresario Already Knows. (Same as in the film industry.) Under John Moriarty at Central City I had three summers in a row of work. Then Pat Pearce took over when John retired, and I was out. Before this, New York City Opera under Donald Hassard hired me for two productions and added a third in their 1995-96 season; then Paul Kellogg took over and I had one more gig (Marco Polo) and that was it for me at the old NYCO. I debuted in San Francisco under Pamela Rosenberg; next season she took a symphony job or something in Europe and I no longer existed at SFCO. I debuted with Washington (DC) opera in THE DREAM OF VALENTINO under Ed Purrington, who the next season retired and was succeeded by an internationally famous tenor; no more gigs there for Adam. I worked two successive seasons in Portland OR under Paul Bailey; he retired; no more Portland gigs. At all these places, my qualifications and performance were never in question; in fact they didn’t matter. I survived regime change at the Met because it has a whole executive tier absent from regional companies: those who choose the covers and comprimarios stayed the same during that transition. But then Lenore Rosenberg retired, no one knows me there anymore, and I’m out, despite a very good audition I did for the new guy there a few years ago.

And finally a sensitive topic, and I won’t name names, but it’s about sexual orientation. Some US companies are famous for hiring singers on the same bus as their impresarios, and those not on that bus are less likely to get hired. And it goes both ways. So to speak. It shouldn’t matter, one’s orientation, but obviously it does. I only mention it because it’s directly related to the question of how operas are cast in the US, and this is indeed a factor.

Another sensitive topic: religious discrimination. Though I never got confirmation for this, it’s likely that I didn’t get hired back in Nashville because I wore one of those little Darwin fish-with-feet pins to a Patron Party. A little old lady came up and asked me, “Is that the Holy Sign?” (read that in a Southern accent) I said “no, it’s about evolution.” “What’s that?” she said. I gave a very short explanation of what evolution is. Never worked in Nashville again.

And then there’s agism, which can’t be stressed enough, or often enough. We have a glut, a plethora, of excellent experienced singing actors all over this continent (and I include Mexico which has tons of great singers) who are basically forced out to pasture when they hit the magic age of Forty-something as the latest conservatory crops come in. Tenure doesn’t exist in opera, unless somehow you become a Name, and then it doesn’t matter how lousy you sing, as long as your Name will still sell a certain quota of season subscriptions. I am singing better now than I did at twenty, at thirty, at forty, or at fifty; yet my agent doesn’t put me up for those roles that Name tenors still sing, or at least perform, into their seventies.

Finally, that little national hire-Americans-first policy that on paper affects every corporation, but in practice doesn’t happen at big opera companies because of, they say, executive/artistic discretion and/or management prerogative. In other words, Management is exempt from this rule because opera is such a personal, person-driven business. This may hold up regarding the international stars whose exotic caché does sell seats no matter what I think of their abilities, but it crumbles when you talk about the cover casts and the secondary roles. I can’t speak for the Canadian educational system, but the USA has plenty of institutions (Juilliard, Curtis, NEC, CCM, IU School of Music, UNT Denton, AVA, to name a few) that churn out singers just as good as any of the Names you see on your local HD screen. But because Big Opera Houses work primarily with select European agencies for their singers, cover jobs are constantly being given now to Eastern European and other non-American singers on that agency’s roster who don’t have our training, but whom this or that Big House assures us are the “best in the world”.

No, Mr. and Mrs. Public: We Americans and Canadians, and Mexicans, are in fact the Best in The World. But you’re not seeing us.

So, there you have some ways operas are cast, and some ways they’re not cast, in the US.

Barczablog: I noticed recently that the Canadian Opera Company inserted covers or second casts into several performances. The new General Director Perryn Leech has been great at employing his covers, including a few Canadians.

Given COVID (which persists) and other respiratory ailments, should double casting be the new normal?

Adam Klein: My only job with COC, in 2006, was as a cover, so that’s been the norm there for a long time, I should think. All my Met, NYCO, SFOC, Seattle and Central City jobs had cover casts. Well, they have apprentice programs to draw from. Most regional companies, though, simply can’t afford more than one cast. Best they can do, and I’ll give a personal example, is have people on standby. During my Edmonton Bohème gig, Monique Pagé and I came down with the RSV outbreak that was sweeping the town and filling the hospitals with kids. (This was 1997, mind you, and lots of people have only just heard of this bug.) Well, what does La Bohème have? Kids. It didn’t lay us up, but it affected our voices to the point that director Michael Cavanagh asked us if he should fly in two other singers just in case we couldn’t sing by opening night. We said no, and we sang all the shows, but the reviewer was unkind to us because of our voices – and then a bunch of schoolkids wrote the paper to complain that the reviewer should have taken into account that we were sick with RSV! Thanks, kids and paper.

The point is, Edmonton Opera didn’t pay for an entire cover cast to deal with that particular epidemic. And as COVID gets more and more normalized, I predict it will be treated like that case of RSV, or a flu epidemic, or the frigging common cold. Bottom line: you feel sick, you stay home.

However, I’ve been in four full opera productions since the COVID pandemic started, and they’ve contained something I’ve never experienced before at a job: fear that I won’t get paid. Because regardless of how SARS-COV-2 affects me personally if I get it, and I’ve caught it, and it’s mild for me (caught it one time while boosted; probably also caught it before there were tests for it), I can’t show up for a rehearsal or performance if I test positive; in fact there’s a mandated quarantine period I must observe. In an office job you get sick leave and a backlog; performing jobs are time-specific/sensitive. Every morning at Spoleto and Chapel Hill’s productions of OMAR, I didn’t know if I’d be going in to work for the next five days until I took the test they provided and it came up negative. That’s a stress I really don’t want to repeat. I don’t want this taken out of context, though. I am a safety-first person and have gotten all the COVID vaccinations and boosters; I don’t want to be responsible for killing a colleague’s grandparent just because we didn’t wear masks that fateful day. I think the politicization of a simple health issue is idiotic, but not surprising given the poor opinion given to science by the general public, in the USA anyway. And whose fault is that, eh? Not answering that, but it should be asked. And dealt with.

Barczablog: Thank you for bringing that up.

In a company the size of the Met with so many performances, how unusual is it for the cover to get a performance?

Adam Klein: Well, that depends on the impresario, doesn’t it. In Volpe’s day, when I came back as an adult, and I believe in Bing’s day when I was there as a kid, covers were trusted and expected to go on if the slated singer became indisposed; and in fact were often given one performance from the get-go. This is how Roberta Peters’s career became big. It worked thus: you hire a really good singer to be the cover, and give that singer one performance in the seven-to-whatever-performance run of the show. This is what I did as Steva in Jenufa: I covered British tenor Chris Ventris as Steva, and British tenor Richard Berkeley-Steele covered Kim Begley as Laca; we sang one out of seven shows, I believe. With Karita: her excellent cover Cynthia Lawrence did not have a scheduled show.

During Volpe I also went on as The Witch when Philip Langridge (whom by the way I first covered as Loge in the earlier Otto Schenck RHEINGOLD production; I also covered him as Aron) took ill, the first year of that dreadful Richard Jones Not-For-Kids production, and I got as far as full dress, prosthetics and makeup during one of the next season’s performances.

We even got a photo of The Two Witches; Philip was SUCH a nice guy. He died of cancer a while after that.

When Gelb took over, this policy changed: he, I was told (and not by him), declared that Only Stars Shall Grace the Met Stage. When it turned out that Stars wouldn’t work for Cover pay, the cover system was left in place – but they now flew in Stars when contracted Stars got sick, keeping the Covers as Covers, so the only way an understudy could go on in those first few Gelb years was if the Star became indisposed during the show. In other words, Roberta Peters couldn’t happen anymore. That first year, I was passed over to perform Steva: to replace Jorma Silvasti they flew in Raymond Very for me to cover. Twice. (And Silvasti is HOW MUCH of a Name?) So I was out about twelve thousand dollars that season. That was bad enough – but we found the reasons they gave for it fishy to say the least, given I’d performed this role just two seasons before. I’d give more details, but I’m not officially retired yet…

If it had just been me, I might not tell this story. But the same thing happened to at least three other cover cast singers in other productions that season, including Kelly Cae Hogan and Raúl Melo. In fact that’s how I met Raúl, at a meeting among AGMA members about this very issue.

So imagine my surprise during Le Cirque des Nibelungen, Season 2, when Stefan Margita whom I was covering as Loge developed a heart condition and couldn’t do the next show, that they didn’t fly Raymond or someone else in, because anyone and his brother can SING Loge.

But as The Albino said in The Princess Bride, “No one survives … The Machine.”

I’m sure Richard Croft who first did the Machine Loge said “no way ever again” if they asked him, because his replaced hips couldn’t take the rake, and Arnie Bezuyen who had covered him and then taken it over must have been inextricably otherwise engaged – however, the probable main reason I was allowed to go on was ore music staff member’s positive report on my singing of Loge during my coaching with him. This is probably the most salient example that all my years of being as prepared as possible paid off. I went on for that show, and then Stefan went home to Europe with his condition, and Jonathan Friend himself tracked me down in the auditorium during a rehearsal for something else and quietly asked if I would go on for the last show, many days from then. So instead of an insert in that show’s program book, I got a bio. That, my friend, is how I went on as Cover Loge not once, but twice. Under Gelb. Did I get any plum mainstage assignments the next season? No, I did not.

Barczablog: Debbie Voigt is shown on the documentary about Lepage’s Ring staging a rebellion in Die Walkure: refusing to follow direction out of safety concerns…

Please navigate this terrain more fully:

-did Lepage make unreasonable demands of his singers ? You spoke of the Rhinemaidens’ vocal challenge, singing while dangling, did anyone else face comparable vocal risk?

-were you braver than others, as you seemed to work really well as a wall-walker

-did Lepage change his plans for the final two operas, in response to her complaints

Adam Klein: Navigate the terrain. Very well put.

The Machine scared EVERYBODY. Its sheer weight was bad enough; its constant software crashes made it even worse. The many moving tongues, each one of which could crush you if it went haywire, didn’t help either. Then there was the bad blood because of the non-union-built set (which WAS The Machine). No one was happy in RHEINGOLD that first season. I can’t comment on the WALKÜRE revolt, though, because I never covered Siegmund at the Met or anywhere else, just did it in concert twice.

I also can’t comment on whether Lepage made unreasonable demands on singers because I never worked with him: I came to the production late, as the new Froh cover, when everything had already been staged, and I got my directions for Froh, and later Loge, from the resident Met AD (Assistant Director): they’re assigned in every production to dole out to the covers the original, Name, director’s pearls of wisdom, and for any production they almost never imparted anything about motivation or other reasons to do this or that move, only simple blocking directions with the occasional warning that if you didn’t go to that spot, you’d not be lit right. (Years back, of course, there was Corelli’s Corner, but no one was paying attention to that by this time, at least I never heard people talk about it. Closest I got to that sort of thing was when I covered Tom Rakewell and the director was giving the company blocking, and Sam Ramey was blocked to do one of his arias from behind a big table; except that when Mo. Levine showed up to conduct the tech rehearsals, he reblocked it so Sam would be in FRONT of the table, DOWNstage. That’s power, Ladies and Gentlemen.)

I do remember that, after the Machine’s final move failed in two different performances, so that the Gods simply couldn’t walk into Valhalla, they came up with a contingency plan that could be implemented at a moment’s notice, once they knew whether the bridge would deploy or not. It was simple low-tech, because it just involved how the singers would get onstage and then off the stage to be replaced by the acrobats, or whether the acrobats would even be used since they couldn’t walk up and then down the bridge if it wasn’t tilting. So before everyone went on for that last scene, we were told which one we’d be doing.

I think I’m remembering that Plan B was to simply stand on the actual deck, down of the Machine, for the whole scene. And maybe walk offstage into Valhalla while the still-vertical Rainbow Bridge shone brightly.

Barczablog Yes that’s what I recall seeing in the high-definition broadcast.

Adam Klein: Did anyone besides the Rhinemaidens face vocal risk? Well, anyone hanging on a wire had an issue with support, but that was mostly the non-singing acrobats, the Rhinemaidens and Loge. As I think I mentioned previously, I took to that wire like, well, a mountain climber to a rappelling rope. Because in my youth I’d done my share of rock climbing, tree climbing and rappelling, and that was on just 600 pound test rope; this was 1500.

So yes, you could say I was braver than some; also I knew how to work the wire so that I could stand on that rake without fear of falling: the roof I’ve been repairing has a similar angle and if I’m standing on it facing downroof, even with my fancy patented rubber-soled shoes I don’t feel secure; and that’s how every singer but me in the RHEINGOLD cast tried to stand on the Machine when it was tilted. Because I trusted the wire, I could stand at right angles to the tilted floor, which was much easier, and which also made it possible to crouch down, stand back up, walk easily side to side on the arc the wire afforded me from its attachment point at the top, and generally make it look like I was on level ground. I could have given people lessons, probably. But I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t scared that any moment the Machine would decide to do something lethal.

Barczablog I could see it. I saw your Loge from in the house and it was completely different from what I saw in the broadcast of the opening. You were totally at ease up there, the most god-like portrayal of anyone in the show.

Adam Klein: Why, thank you, sir. In addition, my technique allows me to sing with my head tilted up, something not everyone learns to do – and you need to point your voice out into the audience. Also, as I mentioned, any tenor can “sing” Loge, it’s all in the midrange, and unlike Tristan or Tannhäuser there are no stamina issues until the speech at the very end, and by that time either you have the volume or you don’t. But you’re all the way downstage anyway. And let’s not forget, in this production, we were miked. For all performances, not just the Scratch, Stream and Radio Broadcast. (The Scratch is a recording of a performance prior to HD Stream Day that they play simultaneously with the live stream, and swap out for it if/when the signal is interrupted anywhere between the stage and the movie theaters. As Julia Child said, “your guests will never know.”)

But we all faced constant physical risk from that machine not twisting how it should, or twisting how it shouldn’t. We were constantly reminded how heavy it was when going to the commissary, because a huge steel I-beam had to be installed to support it: it went the length of the orchestra members’ dressing room and peeked out into the hallway outside the dining area. No set in the forty-plus-year history of that building, no matter how large or elaborate, compared to that thing for sheer dead weight. They could have at least explored the issue of lighter-weight materials… maybe they did… I wasn’t consulted… I’m just a tenor after all… a tenor who can re-roof a house…

I also can’t say anything about Siegfried and Götterdämmerung because I wasn’t in them either. I also didn’t see them or Walküre. Part of my anger management program, which dictates I engage as little as possible in activities that will make me angry. I lost my one chance to perform Siegfried, in Europe, because the Met wouldn’t release me for the production.

Barczablog: Lauren Pearl sang her role on a wire in the opera Gould’s Wall, Marcy Richardson sang Amour in an aerial-themed Orphée. Given your own aerial proclivities, I wonder if you could comment. Is this a specialty we should cultivate?

Adam Klein: What we should cultivate is good physical fitness for opera singers.

Being able to dance is a plus as well, especially if you have a chance in Hades of being involved in a Broadway production. I’m not a natural dancer, but when I got hired to cover Rudolph Valentino in Argento’s opera I took it upon myself to take tango lessons so I wouldn’t be out in the woods at the first rehearsal. (Little did I know that ballroom tango had nothing to do with the kind of tango the choreographer wanted… but I mastered that too…)

There is indeed the dilettante trap, and no one can be great at everything; but the base level of competence among opera singers for anything other than phonation could be raised substantially. The main reason I see for lack of movement/acting/language ability in opera is sheer laziness. Very few of us have chronic or congenital conditions that prevent us from moving and behaving like the characters we’re supposed to be portraying. So I have no sympathy for those who won’t do the work.

Barczablog: I take pride that in my role as manager of mail services at the University of Toronto for roughly 30 years, we established regulations to protect our staff from customers who would overload bags or try to send huge heavy boxes. There are rules & regulations, weight limits protecting the trash collector. Maybe there should also be rules to protect singers and actors from the sort of thing Julie Taymor wanted to do in her Spiderman, or from Lepage’s Machine.

Should the union have a bigger role in protecting singers, establishing boundaries for safety?

Adam Klein: Which union? CAEA, Equity and SAG/AFTRA do have power in this regard; maybe they should use it more often. (That Spiderman points to “yes”.) I briefly mentioned that my union, AGMA, doesn’t have contracts with most regional US opera companies, so anything AGMA might do would affect mostly the dancers, choristers and stage managers at the union houses. (Yes, a stage manager in an opera is a Musical Artist. She does, after all, have to be able to read music. And she works more during an opera than ANY singer. Yet she’s not invited to the cast parties. As Opera Czar I would change that.)

What I would like to see change is the attitude of Management, such that Safety First is just a given. Oh, I saw Lord of the Rings The Musical in Toronto: a stage that moves up and down, AND revolves 360°, AND has eighteen independent moving parts, and all the Orcs are using all four limbs to move about, the arms sporting extensions to make them more like legs. In retrospect I’m amazed no one got hurt that night. Yes, there should be limits to that sort of thing. We’re now just throwing technology at theater pieces thinking it’ll make them better, while ignoring the reason there’s live theater in the first place: HUMAN INTERACTIONS.

Which brings me back to Lepage. I did mention that when I was added to the production I was told that he wanted to focus on the characters’ relationships with each other; but A) that went out the window the moment The Machine showed up, and B) we’re talking about Name Opera Stars here. Many, like me, do take quite an interest in our portrayals and interactions; some do not. One can’t assume everyone will be on board. Then there are parts like Erda: what are you going to do with basically a rock talking at you? Still, it would have been nice, been better, if more attention had been paid to Lepage’s reported wish that this RING was NOT supposed to be about amazing special effects, even if the Machine would have behaved properly.

Barczablog: Opera is theatre. It can be done in a big venue like the Met Opera House, requiring big voices, or in something more intimate. I recently wrote about a pair of upcoming productions of Das Rheingold in western Canada, where one will be in a 2500 seat theatre, one in a 700 seat theatre. The big theatre option seems to be risky nowadays (financially and otherwise), while the smaller option has lots to recommend it especially for performers who can act.

Adam Klein: Small hall or big hall, opera voices need to be big; and acoustics matters more than size. The IU Opera Theater stage was patterned after the Met stage, almost down to the inch, at least the main stage: the Met has thrice the offstage acreage though. But the real difference is in the auditorium section. The Met has an alphabet-plus-five number of rows in the orchestra (ground floor) section. IU doesn’t make it to the end of the alphabet, I think it gets to P. Plus, the heavily textured walls soak up any reverb that might occur. Little-known fact, even to acousticians: the human ear is tuned to the human voice. Therefore, the farther away one is from a source of unamplified music, the more the human voice will predominate, even against brass. Also, the human vocal instrument is essentially a tweeter, not a woofer, so direction matters. Therefore, the one thing you should NOT skimp on, regardless of seat count, is how deep you make your auditorium. What happens at the IU “MAC”? It’s so shallow that singers can’t point their voices anywhere that will fill that space, so they’re constantly drowned out by the orchestra, which is almost completely exposed, as in most halls. They blame singers not being heard on their young age and their undeveloped technique, but it’s the hall that’s killing them.

Vocal size, I have said or intimated, should have a minimum threshold in opera, as long as we don’t amplify it, which I hope we continue not to… ahem news flash: Pavarotti was miked. Battle was miked. Others are being miked. Several of the RHEINGOLD stars were miked not just for the HD but for the house speaker system as well. Why anyone ever produced something with Boccelli NOT being miked mystifies me. Why risk bad publicity for the blind crooner when the Big Boy, the Tibor Rudas-proclaimed World’s Greatest Tenor was miked from early on, basically when he left his native fach to brave the waters of Puccini and the like, and took to hiding his mike in his bowtie? That tidbit I got from someone who sang one of the Pavarotti Plus concerts. Everyone else had mikes on stands except the Man from Modena with his Bowtie Special. I don’t mention this to stir up enmity; I just know millions of people still believe his voice was huge. It wasn’t. Pretty, though.

But to get back to the auditorium issue: hall size also matters less than orchestra size and placement. There is a simple reason singers can be heard at Bayreuth: The pit is covered. Why every opera house built since then, that performs Wagner, hasn’t done something similar (but more humane to the players!) with its pit, baffles me. No one’s voice is big enough to get over a full Wagner orchestra in an open pit. It’s hard enough to get over a PUCCINI orchestra, since he constantly doubles the vocal lines in the strings, and if the clarinet starts playing, forget about it. (People have no concept of a clarinet’s power. Except clarinetists. Luckily they can also play really soft.)

I know I’ll never get my wish for all opera voices to have a minimum decibel level. Vocal technique is still too medieval in its approach, even now, for enough teachers or singers to come to a consensus on what good basic phonation is, much less how to sing Wagner versus Verdi. Each competing technique amounts to a religion with its converts, zealots and detractors, and that includes mine, which now disagrees on fundamental issues with that of each of my own three teachers. I’m a product of all three of them, but I don’t sing like any of them. But the size of my voice has not remained constant from the start.

The first quantum leap came with my first teacher Gloria Hilborn, who knew a lot about resonance and registration. That was in my late teens and early twenties. It got my voice to an acceptable opera size; my second teacher Walter Cassel helped me expand my range and stamina: Walter was an international opera star in his time, singing with Callas, Nilsson, Vickers, Vinay, all of them. So I paid attention, even though his vocal philosophy was almost 180° from Gloria’s. And it got my career started. My problem wasn’t size but timbre. Dramatic voices are gravely misunderstood: I’ve been mistaken for a baritone countless times due to the dark color I get from my high hard palate, lack of tonsils or whatever. People didn’t know what to do with me. But I was filling houses at regional companies with that dark ring of mine for a decade before my Met career started, and that includes my Prairie gigs.

My third teacher gave me squillo, employing muscular adjustments that would have alarmed Gloria, but which I’m living proof do no harm. If you do it right. Curiously, my third teacher stopped using that particular piece of technique in the years between when I left him and when he wooed me back– and I’m gone again, but that’s a very different story. Its relevance here is size. With that added squillo my voice took another quantum leap, so that when I was eventually onstage at the Met with Domingo, I could hear my voice bouncing off the back wall but not his, which surprises me to this day. He’s not known for a small instrument. Well, neither am I, I suppose. Until I sang Heinrich der Schreiber with the late Johan Botha. And that’s another story which I think I’ve already told.

But back to theater size! The acoustically best opera house I ever sang in was the Grand Opera House in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Hands down the best. Seated about 550. Survey the great opera houses of Europe and what do you find? I tell you what you don’t find: auditoriums of three thousand seats or more, built to pack them in to maximize your company dollar. The hall I sang in in Dallas is 3420, the Met’s about 3800; somewhere I could swear I sang in a 4000 seat hall. Unamplified.

So theater designers have a problem: how do I design an acoustically great hall that will also make a profit? I don’t have an exact answer, but they should start with what doesn’t work in the ones already built, and not repeat the mistakes.

Meanwhile, sports stadiums accommodate tens of thousands, and they fill the seats. Amplified.

I don’t want to seem insensitive to the more intimate operas, though. One of my top five, PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE, should NEVER be done in a barn like the Met, for the reason you stated: smaller is better for the acting, and in this case also for the music. If you’re going to put an intimate piece like that on in a barn, then equip it with a Jumbotron so the audience can see the singers’ faces, just like they do in tennis stadiums and the like.

But in my oh so humble opinion, and had I my druthers, no opera house would be bigger than the ones Verdi’s operas were premiered in. They were written for such halls, after all. Lincoln Center should have included a smaller music theater venue: the Vivian Beaumont doesn’t cut it, and of course NYCO’s house was for ballet. Did you know?: the New York State Theater stage and auditorium was designed specifically to DEADEN the sound coming from the stage, i.e. the dancers’ footfalls. Despite this, NYCO had many successful years there, dealing with those acoustics one way or another.

Barczablog: What was your favourite moment as a singer? What moment are you proudest of as an artist?

Adam Klein: What moment have I enjoyed most, and I’m saying “have enjoyed” because technically I’m not retired. That would have to be Mahler’s Eighth with Benjamin Zander and the Boston Phil (not Ozawa’s Boston Symphony), because that experience came the closest to completely fulfilling the composer’s wishes, and the ending is SO cathartic. At least there’s ONE Faust piece that doesn’t end tragically but ecstatically. I’m only sorry no recording was issued of it. But bootlegs were made, and because of one of them I got my first job singing Das Lied von der Erde, in Princeton: the conductor heard that recording somewhere and looked me up. Talk about an audition.

What moment am I most proud of: that would be my performance as Tristan with Seattle Opera: Clifton Forbis had spent the whole rehearsal period and first few performances nursing an allergy or illness of some sort, and he decided to take a day off, so he called me in the morning and said “Go make some money.” (in his Southern accent it sounds even better.) Proudest because the role of Tristan has a legendary quality and mystique about it since so many tenors have crashed and burned performing it. I heard tell of one performance somewhere where three different tenors tag-teamed it one night, as one then the other fell short. So there I was, the Cover, never done the role before, neither conductor nor stage director nor General Manager had heard me sing it, even though I’d been there every performance, singing along with Cliff in an unused dressing room, just to keep fresh. Right before the show, Speight came to my dressing room to tell me not to worry, because this was supposed to be the broadcast performance but he switched the date for that to later to spare me any extra pressure. If he’d asked me beforehand I’d have told him not to worry, but something tells me that would never have happened. I’m not a Name.

As it turns out, I got through it just fine, with flying colors one might say, as the recording of a few years ago in NYC at the Opera America recital hall should attest. I knew I’d have no problems, but knowing that beforehand and knowing it after you’ve done it are two very different things. With the extra money I made, I bought a full wetsuit and tested it off a jetty in a Seattle coastal park.

Oddly, this little triumph of mine led to absolutely no engagements either performing or covering Tristan. The performance I did with Julia Rolwing with Eccentric Theater Company was her idea, and she got my name from my agent. I did it on condition I got to film it and have rights to the film. (The YouTube algorithms threw a copyright claim on it for a video that included the Act 3 english horn solo! I challenged it and the claim was withdrawn.) I also made the conditions that every performer who wanted one got a copy.

Technically my wife Tami was the videographer; I edited it later.

Barczablog: Are there any roles you want to do that you haven’t yet undertaken.

Siegfried would be nice since I pretty much memorized it when I thought I might get to do it in Europe that time.

Peter Grimes again; I did it at IU but not professionally.

Lennie in Floyd’s OF MICE AND MEN but I’m too short.

Apollo on stage: I did it in concert once with piano.

Siegmund in a full production: I did it twice in concert but only Act 1.

Król Roger would be great, after studying the Polish language ten years straight and falling in love with the music of Szymanowski. Which I hope you can tell from the video of the song cycle. Why he’s not up there with Duparc and Chausson in Song Lit Class is, well, he hasn’t had many champions… till now…

I’d like to PERFORM Gandhi instead of cover it. In a production where I get to be pronunciation czar so I can correct all of Constance de Jong’s mistakes. Philip didn’t set the Sanskrit himself. He wrote the melodies senza parole and Ms de Jong picked verses from the Bhagavad-Gita and shoehorned them into place, ignoring prosody completely and getting many vowels wrong.

A word about my “94” Met credits. No one’s file lists the singer’s cover jobs. We have to memorize and rehearse these just like the Names do. A few of mine:

Mephistopheles (Busoni’s Doktor Faust),

Cousin Gilbert (Gatsby – I sang the final dress of this),

Tom Rakewell (I sang the Sitzprobe),

Menelas,

Oedipus,

Aron,

Gandhi,

Herod (while singing Third Jew),

Bezukhov (never even got a coaching for this one),

and Bacchus (coached this with Walter Tausig before he retired – and he uttered the prophetic words “A word we don’t use here: piano.” I. e., much of Bacchus is to be sung piano. Same is written all over Tannhäuser, and we know what happened there.) Long story short, Met covers make more money just covering than most singers make performing. But they get no credit; hence the term “golden handcuffs”.

Pelléas. That would be a good bookend. But they often give it to lyric baritones. Even the Met, featuring Barry McDaniel when I was Yniold. See, misunderstood voice type.

Barczablog: I’m a bit obsessed with the relationship between different types of culture, the way film is changing theatre and opera, the relationship between melodrama & opera, and film music, the ways business concerns change the artform, and the struggles singers face just surviving. Please continue with what you’ve been saying (as in our chats)…

Adam Klein: Mise en scene using puppets, CGI, video, circus, etc. elements. Yes, that stuff is very popular (and not just post-Volpe, and not just at the Met.) Before that era started, Baz Luhrman put Boheme on Broadway, using “age-appropriate” and other-appropriate performers. I didn’t see it, I didn’t audition for it. But I remember Linda Ronstadt’s comment after she performed Mimi: “Opera is hard!“

Now I’m no fan of the stereotype horn-helmeted obese woman image of opera that’s still in the mind of the general public. Before throwing tech at opera thinking to reinvent it, try to make it fulfil its intrinsic potential by raising the bar on the interpersonal front. Opera is a synthesis of many art forms simultaneously, and the only one that has traditionally been skated on is acting. That has added to the stereotype that opera singers are stupid – because they can’t act, supposedly. But for most of my gigs, indeed all of them except ones at places where Park and Bark refuses to die, I’ve had the privilege of working with many singers who give their all on the acting side as well as the singing side. E. g., Phillip Ens is my favourite bass — well he splits that title with Vladimir Ognovenko, but Phillip’s voice is prettier. He’s just a natural actor, nothing he does is contrived. And I’m not trying to single him out. Central City, Indianapolis, all my Prairie Provinces gigs, Memphis, Spoleto, Wilmington, Boston: everwhere there’s an opera company there are quite competent acting singers and singing actors. Now what does acting have to do with Julie Taymor’s deadly Spiderman production and the Bunraku Butterfly? And of course the amazingly distracting moving graphics projected onto the Machine in Lepage’s RING? To repeat, opera has to start with great singing. The tech matters nothing if we don’t deliver that. Second, even in stereotypically described “ridiculous” opera plots such as LUCIA, if the performers interact like actual human beings instead of statues, if their movement is organic instead of a slide show, then you get DRAMA irrespective of the singing, which COMPLEMENTS the singing, just like the sets, costumes, lighting, and musical arrangement are supposed to do.

Now I’d like to add something to what I’ve said about Le Cirque Des Nibelungen. Of course one can blame Lepage for not making sure enough time was spent developing the characters and their interchanges, because the buck does stop with him; but so much went on with the Machine constantly crashing (WINDOWS operating system??? “Really???” – we all thought) and the threatened strikes because of the non-union set builders, that I believe something still considered by many in the opera business to be as unimportant as performer interplay was just thrown to the curb. The show must go on, and there are only so many hours in the day, and instead of Lepage’s vision of a well-acted AND acrobatic RING cycle, we just got more of the same Met park-and-bark with lots of tech thrown in. Criticize Lepage all you like: it was NOT his fault that time simply ran out. Was it?

I gave the tech a chance. As the Froh cover I watched the opening scene between Alberich and the Rhinemaidens, from the house, during the first full tech rehearsal and subsequently. I couldn’t take my eyes off the stones falling from where the Rhinemaidens’ flippers were hitting them. There was no chance of my being able to even try to see if anyone was interacting, from that and being aware that those Rhinemaidens were also suspended on wires while singing. What that must have done for their ability to breathe, without getting at all technical vocally. No matter what vocal religion you follow, we all have to breathe in before we can breathe out to phonate. Later on, as Loge, my wire only held me from behind, it didn’t suspend me, so my breathing was not so affected. Not the case, I’m sure, for the Rhinemaidens. So right off the bat when I get there I’m seeing things that are subverting anyone’s desire for this production to be as realistic as possible. It had “Eurotrash” written all over it.

And my definition of Eurotrash is something like: Take a tried-and-true opera and do everything you can to make it not work as intended, and if you can manage it also make it as shocking as possible, because we’ve done Traviata a thousand times and no one, we believe, wants to simply show up and watch a period-correct Demimonde salon when we could set it in, say, a crack house. Unfortunate if this is what people think Lepage was after.

Barczablog: Another obsession? The Canadian singers’ plight (especially since the pandemic) seeking employment when artistic directors often will import rather than develop domestic talent. I’m curious about how it’s been for you, and whether you’ve found that the USA is more welcoming to your own domestic talent (meaning people like you).

Adam Klein: I very much like the way you approach these things. Okay, context. First, some of my Canadian history. Break-in gig: I replaced Claude-Robin Pelletier in Regina in 1995 or 6 for their RIGOLETTO; then Irving Gutmann brought me back for five more gigs: three in Edmonton, two in Winnipeg. Lucia, Butterfly and Boheme in Edmonton; Boheme and Butterfly in Winnipeg. When Irving retired, as you might expect, I didn’t get any more gigs at his former companies even though Michael Cavanaugh seemed to like my work. So my next and so far last CA gig was with COC, covering Mime in their (then) new RING cycle. Then Bradshaw died and I didn’t get asked back although the Higher Ups were giving good reports about my work. Mind you, I have no problems with Canadian companies giving the jobs to Canadians; I wish that would happen more in the States as well — at the big companies.

Barczablog: I wish I could report that Canadians got the work. With the COC here in Toronto Ben Heppner sang Tristan but otherwise we’ve been importing, especially in your fach. Perhaps we’ll see an improvement with Perryn Leech (as I mentioned above), but so far it’s status quo, as in mostly imports. I was frustrated by the recent Fidelio in Toronto, where the two import leads couldn’t sing on pitch. As I’ve said before, better to have incompetents who are Canadian.

Speaking of Canada as a whole, though, it’s far more nationalistic possibly because Canadian artists aren’t as expensive as the imports. I’m an idealist but it’s business pure and simple. That’s what Gelb would tell you, and what our Canadian general directors would say as well. In Quebec there’s a genuine nationalism where francophone artists build careers (indeed that’s where you friend Lepage got his start after all. Yannick too. I saw his Pelleas in Montreal when he was very young). Across the country you find Canadian artists, although come to think of it, the comparison between those two Alberta Rheingold productions I spoke of recently (upcoming this spring, in Calgary and Edmonton) are contrasted both in size and in the casting philosophy. Edmonton’s seems to be 100% Canadian, where Calgary’s resembles Toronto’s approach, almost entirely imported talent. I guess this corresponds to the USA, where you have bigger cities with big companies using the imported stars and also regional companies who give work to American singers.

Adam Klein: The regional companies simply can’t afford the money or hassle bringing in foreigners (or STARS) most of the time. But despite the hordes of American opera singers out there, a place like the Met deals with foreign agencies for most of their singers, on the assumption that American opera fans think that opera stars have to be exotic and not homegrown, Richard Tucker and Leontyne Price notwithstanding; and this practice now includes the cover tier more than previously, even with that “fill positions with Americans wherever possible” edict in place, and American singers are at least as well trained as Europeans and sing at least as well, too; there’s no excuse for how many Americans are NOT at least given cover work at the Big Houses.

Speaking of which, I haven’t sung at the Met since the 2015 season when Botha did his last Tannhäuser there; I was Heinrich der Schreiber. I wrote to Someone In Charge There early the next season, simply asking for advice about my career; but her answer was “The reason we didn’t have you back this season was that we simply couldn’t hear you in Tannhäuser.”