The Metropolitan Opera’s 2023 production of X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, the 1985 opera with libretto by Thulani Davis and music be her cousin Anthony Davis, was shown on PBS over the past week, likely as a nod to Black History Month. Although I’ve seen Davis’ music described as jazzy or jazz-inflected, except for the scene in Boston with the street, I think that description is unhelpful and misleading, possibly meant to encourage listeners to take a chance on the work. The score reminds me of Stravinsky or Zappa in its willingness to build melody from jagged shapes, and to make meaning through repetition. The frequent repeated cells do not in any way make the score minimalist even if at times –especially in the most spiritual moments such as the hajj undertaken by Malcolm– we are hearing chants and repeated phrases.

The libretto is an impressive creation, entirely intelligible to my ear. The ability to write phrases that can be understood seems to be an elusive goal, given libretti that lose track of the need for simplicity, of the fundamental transactions in drama seeking to communicate meaning to an audience. Thulani Davis makes poetry out of long thoughtful aphorisms that when repeated have the power of the spiritual, even if the opera didn’t already have the religious context hanging over the piece. I may have lost my objectivity, listening to this work at this particular time.

My headline may seem absurd when one recalls that Malcolm had a conversion experience in prison, discovering Islam through Elijah Mohammed. But I’m talking about my encounter with the opera via my own path & my own spiritual journey while watching the Met on PBS. I’m looking through so many lenses I may seem to be like a kid holding his binoculars backwards, peering in at the wrong end. Yet maybe that’s the right way to address fundamental questions of faith.

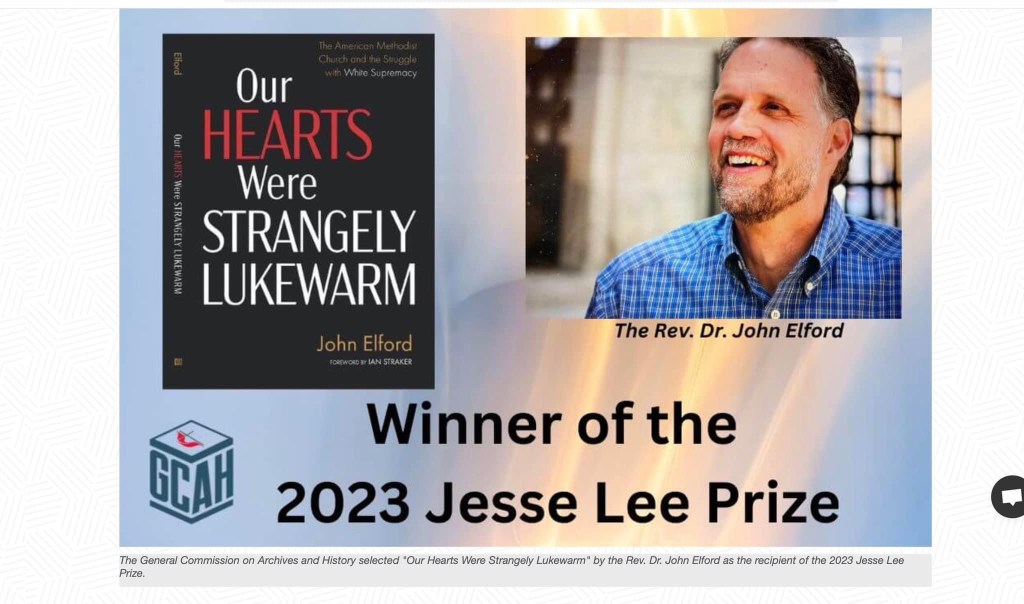

I’ve been reading John Elford’s award winning book Our Hearts Were Strangely Lukewarm, subtitled The American Methodist Church and the Struggle with White Supremacy.

I came to the book through social media, where I’ve followed John, a classmate of mine from over half a century ago. John’s book is a careful history that is easily readable regardless of whether you’re a scholar or not, written in very direct language that doesn’t mince words.

His title might be the best signal, a poetic snapshot of the cognitive dissonance suffered by those perplexed by a church that fails to live up to what Jesus preached or what the founder John Wesley laid down as guiding principles. “Strangely Lukewarm” as the church sometimes seemed not just quiet about slavery but even speaking to endorse slavers. Or at least the church wasn’t as zealous in opposition as it might have been. Yet John is not judgmental or simplistic in his exploration of the different branches of the church.

Let me just say that Christianity is hard. You think about it on Ash Wednesday or Easter, when the teachings of the Gospel challenge us. I try to remember not to judge, not to presume to speak of what others are going through when I haven’t walked their walk, when their journey is so different from mine.

Reading John’s book recently I was mindful of the whole question of communities of faith and how we choose to belong or resist being in such a community. My own path, as a child of a single working mother, left me with a memory of church and Sunday school, but into adulthood without any connection to a congregation. How happy are those brought up in the bosom of a church family. I noticed this especially at funerals for church members, surrounded by members who may treat the departed as a saint of the church.

I was startled by how much I identified with Malcolm X in his journey. He loses his father early, and his mother is so distraught that the children are taken from her and placed in care. I remember that when my father was dying my siblings and I were taken into the home of our Pastor and his family for a time, while my mom lived beside my father in his hospital room. (or so it seemed) Even then when I was only 5 years old, I knew my mom was distraught by what had happened.

Malcolm’s youth is presented with the jazziest music in any part of the opera. The seedy community life in Boston living with his sister is dominated by Street, a charismatic tenor character so reminiscent of Sporting Life from Porgy and Bess that I have to think the similarities are deliberately built into the opera. Sporting Life is the agent of corruption, tempting Bess with happy dust (cocaine).

We see Malcolm (sung by Will Liverman) end up in prison perplexed by the futility of his life so far, listening to his brother recommend another pathway that he himself found, via Elijah Mohammed.and the Nation of Islam. As this idea revives a despondent Malcolm we will meet Elijah, another charismatic tenor character played by the same singer as Street (Victor Ryan Robertson) even as he inspires him in the opposite direction.

Malcolm X begins his own ministry throughout the USA, an electrifying speaker who helps the Nation of Islam grow in the decade from 1954-1963. But Malcolm’s words after JFK’s death bring him into conflict with Elijah, who commands Malcolm to be silent for a time.

We come to the most spiritual portion of the opera, as Malcolm decides to trust in Allah to help him, going to Mecca on a pilgrimage. The chorus are chanting behind many of Malcolm’s lines. I felt solidarity with him as a stranger in a strange land listening to chants in another language, as he sought meaning and clarity. I found his demonstration of humility touching, his conclusions about unity moving.

As for the rest of the work leading us back to USA and Malcolm’s assassination in 1965, the opera does its job with remarkable economy of means. When I think of the time put into the deaths of most opera characters, whole arias devoted to their last moments, this is so brief as to take your breath away. You barely have time to register that yes, the onstage banner tells us it’s the Audobon Ballroom where we may remember that Malcolm was shot, and we see that Malcolm is on stage with the child version of himself, Young Malcolm who we saw earlier in the opera. I was grateful for this merciful choice considering the brutality of the event.

The Met production features dancers choreographed by Ricky Tripp working in a variety of styles, sometimes African sometimes American, sometimes suggesting other cultures. They underline many scenes like a non-vocal greek chorus, married to the story-telling, and underlining the energies of the music. They expand our sense of a community in each scene where they appear.

Directed by Robert O’Hara with projections designed by Yee Eun Nam, the story unfolds before us on multiple levels, something like what we see in the current Toronto production of Cunning Little Vixen, where details and motivic elements are projected before they’re enacted. The stage space is rarely employed in a way that I’d consider representational or realistic, but rather in a series of scenes suggesting something static like oratorio, the singers at times standing and delivering as though preaching, and I don’t limit that to the two actual preacher characters (Elijah and Malcolm). Everyone including Malcolm’s brother Reginald (Michael Sumuel), his sister Ella (Raehann Bryce-Davis) and the dual roles of Malcolm’s mother Louise & his wife Betty (both played by Leah Hawkins) are given moments of declamatory singing that wouldn’t seem out of place in a Bach oratorio.

It’s wonderful singing, beautiful music, some superb dance in an opera I wish someone would present here in Toronto. I know we have the talented singers who could undertake the main roles if someone would produce this fascinating work.

I’ve saved the opera on the DVR where I will listen again.