Book titles can be funny. I didn’t really understand what John Elford’s book was doing when I saw the cover. But then again I suppose that’s why we read books, to answer the questions they pose.

Sometimes art functions as a security blanket, as an escape, as a way to cope, as a pain reliever. I say that as I ponder a year that felt like purgatory.

And I kept starting books that I was unable to finish.

Last winter I had two books before me:

1) John Elford’s Our Hearts Were Strangely Lukewarm, a history of White Supremacy in the Methodist Church

-and-

2) American Prometheus, the biography of Robert Oppenheimer that is behind last summer’s blockbuster film.

Excuse me as I interrupt my own chain of thought, as I suddenly remember the origins of that metaphor “blockbuster”, a name for an explosive device that used to be understood as something nasty before the later bigger benchmarks for nasty devices were invented, dwarfing blockbusters. Some readers may decide I’ve taken leave of my senses in choosing to focus on such things. But that’s very much where I’m headed in this discussion, for better or worse. It is no wonder that we’ve lost our sense of proportion, our sense of what these words mean: given the context.

At first glance one might think the two books are so far apart in subject matter that my choice to connect them is a kind of non sequitur. Let’s see.

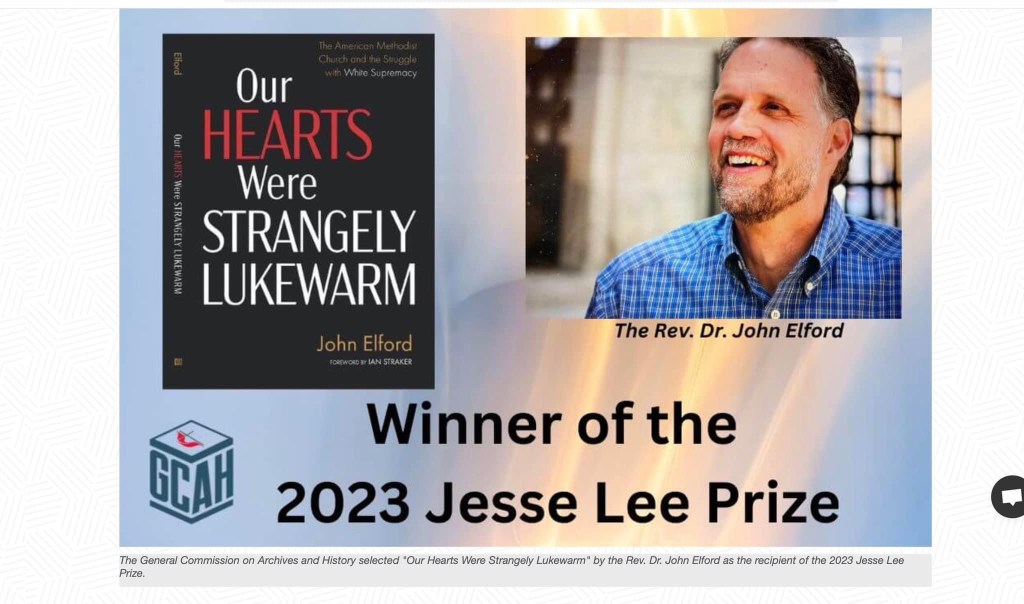

I stumbled upon this book by accident. I went to school with John Elford long before he became the Reverend John in the Methodist Church in the USA.

I try to be a loyal supporter of friends, buying their art, seeing their concerts and plays and operas. And I’ve reviewed a few books by friends, hoping that the somewhat guileless persona I wear on the blog conceals my shortcomings.

I don’t want to pretend to bring any sort of authority to a conversation about a religion (the Methodist Church) that I don’t pretend to understand, or a profession (ministry) that’s far beyond me. While I’ve stepped into the pulpit a couple of times to talk about music, while I think of the music we make in church is a type of ministry: yet it’s not to be mistaken for the work of a preacher.

When I got the book last year, first I thought I’d write something for February / black history month, but wasn’t done reading it yet.

Or maybe for Juneteenth. Nope again.

Now having finished re-reading it I found it felt more timely alongside the Republican Convention, maybe because John is writing about white methodists most of all, even as it does also concern persons of colour within the church.

The title is brilliant because it belies the intensity of the book and its subject. Rev John titled it “Our Hearts were Strangely Lukewarm” but I had a strong response, a study of the history of the methodist church and its complacent participation in white supremacy. I didn’t expect it to be so powerful.

Ever wonder how we got here? That seems like a valid question especially in a year when people seem intent on turning back the clock to another century. My idea of “here” may surprise you, as I am feeling much better about America than I did the week after the Presidential Election. The other books provide the context for that conclusion, but alongside Rev John’s book.

American Prometheus led me to a pair of books that frame America for me as we go into 2025.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog you may recall my quibble with Oppenheimer, a film that rubbed me the wrong way, as I lauded Fat Man and Little Boy while lamenting the shortcomings of the recent bio. I couldn’t put my finger on it until this very moment as I write this now months later. I wrote that I was disturbed by how clinical and cold Oppenheimer felt, compared to the earlier film, that Roland Joffé (director) and Ennio Morricone (composer) gave us something far more powerful even if the recent film may be more accurate. I now realize why that presumed accuracy is bothering me so much, in context with the November 5th election, and the other two books.

Joffé’s instinct –that it was Leslie Groves not Oppenheimer who really led the Manhattan Project– is shown in a film that put the general’s picture (Paul Newman) not the scientist’s picture on the poster for the film. Yes, Paul Newman was a bigger star than anyone else in the film. And the story made it clear who was really the driving force, and why the director chose to centre the story upon the general rather than the physicist.

That’s what led me to a disturbing book, namely Racing For the Bomb (2002), a biography of General Leslie (Dick) Groves by Robert S Norris.

I was intrigued to discover that in addition to being the project manager for the Pentagon, that Groves was in charge of the camps for the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans. Groves was in charge of the procurement of fuel, the development of the bomb, its delivery and its targets. You could say that Dick Groves was the architect and builder of the Military Industrial Complex.

The affable portrayal from Matt Damon as teh General in the recent film is far off the mark of what you read in this book. Here’s one tiny example.

General Groves is the biggest SOB I have ever worked for. He is most demanding. He is most critical. He is always a diver, never a praiser. He is abrasive and sarcastic. He disregards all normal organizational channels. He is extremely intelligent. He has the guts to make timely difficult decisions. He is the most egotistical man I know. He knows he is right and so sticks to his decision.

(p 210 Norris)

Then I stumbled upon a book that disturbed my sleep for much of the year. Nuclear War: A Scenario is a huge best-seller that came out this year. It was triggering for me, as a kid who grew up watching Dr Strangelove, On the Beach, and saw The War Game (!966) in school, when shown to us by an enlightened teacher at UTS. When Goldwater lost to LBJ in the election of 1964 (when I was nine years old) I slept somewhat better, yet fears of atomic war lurked in my psyche, ready to be brought back by a book such as this new one. Let me set aside the actual content of the book, as it should scare the pants off you, if you read it. Annie Jacobsen includes a series of parenthetical history lessons, such as ICBMs and the doctrine of “Launch on Warning.”

The most impressive thing I read in this book–and the thing that links me back to Dick Rhodes and yes Rev Elford’s book– is not its careful descriptions of the intricacies of war (that my younger nerdier self would have obsessed over), but the thinking behind all of this, when Jacobsen observed the similarities between the planning of the Wannsee conference when the Final Solution was laid out in the 1930s by Nazi thinkers, and the more recent planning for nuclear war: a mind-boggling event leading to the extermination of hundreds of millions of people, and perhaps the end of all human life. Committees can be terrifying even as they ignore the implications of their decisions. I am grateful to Jacobsen for daring to say this, to the apes on a treadmill.

The one strange consolation for me is in seeing the way that genocide was somehow neatly compartmentalized in the minds of planners. I see a pattern going back decades. Now I see the reason Christopher Nolan’s film was so sterile, the same sad symptom: that we are not really looking at reality–the way Joffé bravely and painfully does in his film– but hiding away in a realm of abstractions. It has me feeling better about the things I see from the recent election, suggesting to me that the F word really is not a new phenomenon, not when we recall Leslie Rhodes’s work on internment camps, and so many other things going back to the innocent events in the history of the Methodist Church, the topic I began to address. I hope Rev John will forgive me for suggesting the link.

The title is perfect. And the puzzle as you wonder what it means is immediately solved by an explanatory subtitle to explain. John Elford’s award winning history Our Hearts Were Strangely Lukewarm is subtitled The American Methodist Church and the Struggle with White Supremacy.

In the review I published a few months ago of the Metropolitan Opera production of the Davises biography of Malcolm X, I repeated the observation that Christianity is hard. No I don’t pretend I’m original in saying this, but to be a Christian is to contemplate ideals that are daunting when one reads what Jesus told us to do. In fact one of the best demonstrations of being a Christian might be seen in Rev John’s book, not just in recounting the many times different factions within the Methodist movement came into conflict with the leadership of the church.

I did not expect to feel so good when I came to the last parts of the book, telling us of people trying to make amends, and even reparations. I never knew anyone had actually tried that, although indirectly, as in financing black students or micro-loans to help people start businesses. It’s inspiring. I mention it at least in the spirit of wanting to offer something positive after all the negativity you see in this review. I long to bring joy rather than sadness.

If you are looking for a positive and inspiring gift at Christmas time, look no further than Rev. John’s book, that I would call at least part of the answer to the question “how did we get here”. The committees dividing the Methodist Church remind me of the discussions Annie Jacobsen speaks of in the planning for war. I don’t know if the apes will ever get off the treadmill, whereby we avoid the outcome (who does after all), but a first step is in taking a good hard look in the mirror, as Rev John and Annie Jacobsen both do.

Pingback: Falling for Sky Gilbert’s Shakespeare Lied and other bardish books | barczablog