My interest in Ronald Royer is complex.

Ron was a teacher at my school, although I was only dimly aware of that because Ron arrived at the school long after I left.

I encountered Ron as Artistic Director of the Scarborough Philharmonic Orchestra, an ensemble I have heard because I live in Scarborough and seek to support them.

I listened to music he composed. I went to concerts he curated and conducted.

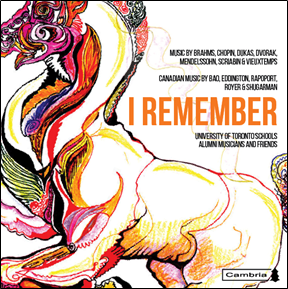

I also watched him bring people together on projects that impressed me, such as the CD in 2018 from University of Toronto Schools titled “I Remember. Yes I’m an alumnus of UTS.

The closer I looked, the more I admired the work Ron was doing in my community. Yet Ron is so modest about the life he had before arriving here, his amazing experiences. No wonder he is leading a meaningful life of creativity building something wonderful in my community, a composer, a musician and an excellent teacher who cares about people.

Very soon he will lead a SPO concert titled “Joy” coming up on March 22nd.

They’re playing the Bruckner Te Deum and Beethoven‘s Symphony No. 9. If you saw the interview I did recently with Holly Chaplin you may recall that she mentioned this concert, which features her as soprano soloist.

Joy indeed!

I’ve been listening to and admiring Ron for literally years. I’m overdue to interview him.

*******

Barczablog: Are you more like your father or mother?

I am closer to my mother, especially in appearance and personality. Virginia DiTullio Royer had a friendly personality, loved the arts, loved Italian food, was a night owl, and had a passion for music. She was an excellent pianist who focused on chamber music and accompanying. She was part of a successful family of professional musicians in Los Angeles, including her sister, flutist Louise DiTullio and her father, cellist Joseph DiTullio. There was a time in the 1950s when 5 members of my family played in the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the same time. On my grandmother’s side, there were musicians going back generations. I heard a lot of live music in my house and at my grandparent’s. It is hard to know how much of my love of music is from the genetics on my mother’s side or having so much music in my life.

While I am less like my father, Richard, he also influenced me in many ways, including the love of learning.

BB: Who do you like to listen to or watch?

I love listening to all types of classical music, from early music through today’s new music. I also enjoy listening to film music, jazz, musicals and world music. I enjoy watching movies, from older classics to new movies. I am not a fan of horror or violent/gory movies, but like most other genres. I have a particular passion for watching movies with great film scores. Pretty much any film with a John Williams or a Jerry Goldsmith score will get my attention. As well, there are many other terrific film composers I am a fan of. I enjoy some TV shows and recently watched the Young Sheldon series and thought it was quite funny.

BB: What is the best or worst thing about what you do?

Being involved with music is the best. Making music with other musicians is a joy, and teaching is rewarding. Composing is an engaging and enriching process. Each of these activities have different benefits. I really enjoy working with people, whether adults or students.

However, it is also valuable to have personal time where I can compose, study scores to conduct, or practice the cello.

Doing administrative work is less enjoyable but needed. Whether it is marking papers, attending staff meetings, or doing admin work (e.g. as part of my music director position with the SPO), it needs to get done. Keeping a positive mindset helps make the admin work less of a chore.

BB: What ability or skill do you wish you had, that you don’t have?

I wish I could have had skill as a visual artist. I had a great uncle who was an excellent pro violinist, who when he retired took up painting water colours and was quite good. I also wish I could be a good cook. My wife can make up recipes and tell when food is cooked by the smell.

BB: When you’re just relaxing and not working, what is your favourite things to do?

My wife and I love to travel, especially to places that have a concentration of culture and history. We are not into camping but like to stay in hotels when vacationing. We enjoy going to museums, plays, musicals, and restaurants.

Five years ago, I started the sport of Curling. Besides being an interesting and challenging sport, it has the tradition of being a social activity too. After the game, the winning team buys the losing team a drink, and everyone sits around and chats. I have been taking some private lessons and working to throw the granite rocks with some accuracy. I am enjoying the curling and the company.

Bb: What was your first experience of music?

When I was a baby, my parents would play classical music records for me. They would regularly play the Beethoven violin concerto and the triple concerto, and the Brahms violin concerto and the double concerto. I can still remember listening to this music in my crib and loving it. When the record would end, I would cry for more.

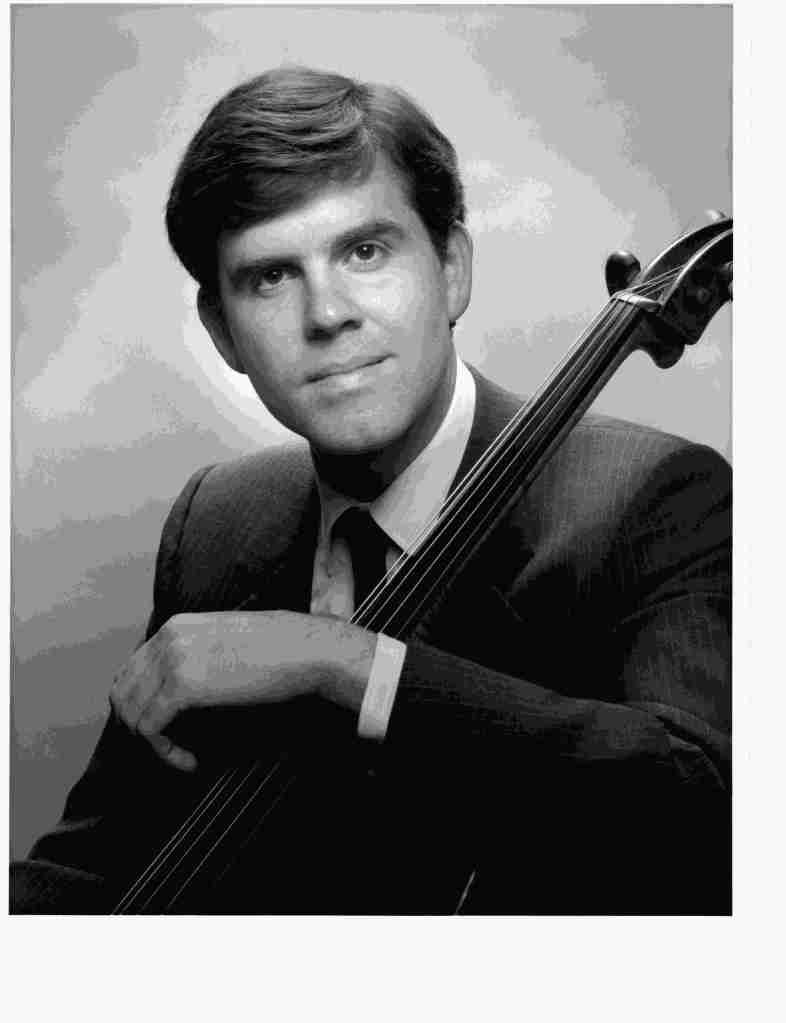

BB: Tell us how you became a cellist.

As a toddler, on Saturdays, I played in my grandfather’s music room while he taught cello. Throughout my childhood, my mother would regularly rehearse with my grandfather and aunt at our house. My mother was also regularly rehearsing with my grandfather’s cello students. I heard a lot of cello, piano and flute. My mother started teaching me piano when I was 6. I don’t think I was ready yet to get serious about music, plus I didn’t bond with the piano. At age 10, my mother asked if I would like to play another instrument, like the cello, flute, violin, horn, or oboe. These were instruments family members played professionally. The sound of the cello had always been appealing, so it was an easy decision. At this age, I was much more receptive to studying music and I made quick progress. By the time I was 16, I decided I would follow in my family’s footsteps and become a professional cellist. Little did I know that my music career would include much more than playing the cello!

BB: I heard your first concert with a major professional orchestra didn’t go as expected.

While in university, I spent three summers playing in the orchestra and studying cello at a music festival in Snowbird, Utah. During the 3rd summer (in 1980), a cellist in the Utah Symphony broke their arm, and the regular subs were out of town or not available. The symphony decided to have auditions for the cellists attending the music festival. I auditioned and won the opportunity to play the summer season with the Utah Symphony.

My first concert was a runout to a park in Ogden, Utah. The concert venue had a makeshift stage with no roof. We were rehearsing and it started to rain, so we stopped. The decision was made to sight read the rest of the music during the concert. This day was not going to expectations! We started the concert, but after a while it started to rain. We took a break. After we started again, it started to rain again. Our conductor had an idea. He asked for volunteers from the audience to come to the stage with their umbrellas and hold it over a musician, so that our crew could set off the fireworks and the orchestra could play one more piece. The orchestra was quickly covered by a sea of umbrellas. However, we couldn’t see the conductor, which was a problem. Our performance was not perfect, but the fireworks were making plenty of noise to cover up our imperfections. I was doing my best to play, but then something hit my right arm, bumping my bow off the cello string. I looked over and saw dogs running through the cello section! At the end of the concert, the principal cellist said to me, “I bet you will never forget this concert!”. He was right.

While this was the only time in my career where dogs ran through the orchestra, many years later I performed in what was billed as the first orchestra concert specifically for dogs. The IAMS dog and cat food company sponsored conductor Kerry Stratton and his Toronto Concert Orchestra to perform on the CNE grounds for a free concert. There was a lot of publicity surrounding this event!

Dogs brought their masters to a lawned area so they could comfortably listen to a concert programmed to be appealing to dogs. We did a medley of famous dog themed pop songs (e.g. Who Let the Dogs Out), among with classical and movie favourites. The dogs were quite well behaved.

BB: Ron, tell us about your Los Angeles career as a gigging cellist.

I started my career as a free-lance musician in Los Angeles in 1980. I had the opportunity to play various types of music, from classical to film scores, musicals, pop, and jazz. When I was starting, I got a fortuitous break and was accepted into the New American Orchestra, led by a prominent film composer, Jack Elliot. Jack believed that the true American artform was jazz, so we did a lot of symphonic (third-stream) jazz. When I started, the principal bass was Ray Brown, who was Oscar Peterson’s bass player for many years. Sitting in front of Ray, I received quite an education on how to play a walking bassline!

Some of the artists who performed with us were Frank Sinatra, Dionne Warwick, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Eckstine, Gerry Mulligan, and the Modern Jazz Quartet. As well as performing jazz, Jack would bring in prominent film composers to conduct music from their scores. Being able to play music from Star Wars and E.T. with John Williams conducting was a treat. Most of the music the New American Orchestra played was commissioned, with prominent jazz and film composers making up a big part of the list.

Henry Mancini (we called him Hank) used to regularly perform with us. Performing the Pink Panther theme with him conducting was a blast! His body language told us how to get into the right grove and make the music fun! He composed Piece for Jazz Bassoon and Orchestra for our orchestra. We had a terrific musician in the orchestra, Ray Pizzi, who could play multiple instruments, including sax, flute and bassoon (called in the business a doubler). Ray made the bassoon sound hip and cool, and like Hank, made the music fun. We performed this work several times, with the audience always loving it. Besides being a great musician, Hank was a friendly, kind, and generous person, who had an impressive ability to remember everyone’s names (including mine).

Another standout experience was playing in the pit for a touring production of the King and I starring Yul Brynner, in 1983. During this run, we celebrated Yul’s 4,000 performance of this classic musical.

Yul was in bad shape with inoperable lung cancer. His prognosis was not good, but Yul was determined to keep performing anyway. For some shows, he could hardly talk, much less sing. That said, Yul had great onstage presence, and he found a way to give terrific performances. In each show, he would make some changes to his dialogue, finding a way to make the show unique and special. He often found a way to make the musicians in the pit laugh with an inside comment. I am sure the audience would wonder why we were laughing. Each show, he received a standing ovation. The tour did have to shut down for a few months while he received painful radiation therapy to shrink the tumor, but Yul went on to live until 1985 giving a total of 4,625 performances of the King and I. In both acting and fighting cancer, Yul was an inspiration.

BB: Tell us about some of your Hollywood Film and TV experiences.

Working in the Hollywood studios was quite an experience, with a number of highs, but also some lows. Having the opportunity to work with major film composers like Jerry Goldsmith, James Horner, Maurice Jarre, Henry Mancini, Lalo Schifrin, and many others, was inspiring and eventually led me to start composing. As for the work, I would be called to go to a studio on a particular day and was expected to sight read music I had never seen before, accurately and musically, no matter the style or difficulty level. We would run it once and then record it. You had to figure out and learn the music fast! Some recording sessions were not too hard, but others could be quite challenging. Because you were hired by the gig and had no job security, everyone had to develop a can-do mindset, with failure not being an option. Again, it was inspiring to be in such an environment, where everyone was determined to make the newly composed music sound great.

Some of my favourite projects that I worked on were the movies Children of a Lesser God, Footloose, Gremlins, Lethal Weapon, Star Trek 3 and 4, The Last Starfighter, The Outsiders, Young Doctors in Love, and TV shows such as Dallas, Little House on the Prairie and Fantasy Island. As a teenager, I had enjoyed the original Star Trek TV show. Being able to play for two of the Star Trek movies was a fun experience. One memorable moment during a Star Trek III: The Search for Spock session was when the director Leonard Nimoy, and the composer James Horner, stood in front of where I was sitting in the orchestra and had a conversation about the music we just played through. Leonard Nimoy, who was professional and friendly, suggested that James’ music involving two Vulcans (including an adolescent Dr. Spock) had too much emotion, because Vulcans don’t have emotions. I thought, how can James have any less emotion in the music he composed? At the end of an impressively unexpected but ultimately diplomatic argument, Leonard Nimoy decided to accept the music and not require changes. Not all interactions I saw between a director and a composer were this creative, subtle or polite.

Sometimes there were challenges. For example, Jack Elliot was able to convince NBC executives to hire the New American Orchestra for a live 2-hour primetime TV show in 1981 called LIVE FROM STUDIO 8H: 100 YEARS OF AMERICA’S POPULAR MUSIC, featuring Paul Simon, Sarah Vaughan, George Burns, Henry Mancini, Gregory Hines, Steve Lawrence, and Eydie Gorme. Studio 8H was where Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra had performed, and during the last 50 years, has been the home of Saturday Night Live.

The show was mostly singing and dancing, along with some jokes by the elderly and funny George Burns. I was really excited to have this kind of opportunity to see New York City for the first time! Once in New York, I realized there was a problem: NBC had hired a director who didn’t really care about the music. We were in the city for a week of rehearsals, and most of the time the orchestra was not allowed to play, so the director could work on lighting, camera angles, etc, On the day of the show, our conductor had to argue with the director to give us some time to play through the music, most of which we hadn’t played yet at all. We started rehearsal at 9am and with minimal breaks, it went to 8:30pm. It was a wild day of trying to learn the music and figuring out how the show would run. At 9pm, we started the live show, but the crew didn’t turn up the lights for the orchestra, so we couldn’t see the music to start playing. Our conductor yelled, “improv in D“, and the orchestra started playing. For me, it was a bit scary making it up on national TV. The show had its challenges, I think most (if not all) of the performers felt stress, but we managed to get through it.

One of my most memorable performances was playing for the Grammy Awards in 1990. Sir Paul McCartney and Miles Davis received Grammy Lifetime Achievement awards. Despite the producers spending a year carefully organizing every detail, it was amazing how many things went wrong behind the scenes. Right before the show started, I was talking to the conductor, Jack Elliot.

He mentioned some of the problems:

Stevie Wonder was stuck in rush hour traffic coming to the theater.

And Paul McCartney was off schedule. Nobody knew if his flight from England would arrive on time for him to perform and receive his award.

There was other drama as well. Miles Davis appeared to be high on drugs.

And supermodel Christy Brinkley showed up wearing a red silk dress despite there being a formal black dress code.

The producers looked a little stressed to me, but they and their team dealt with the situations and did everything they could to make the show a success. Stevie made it to the theater in time to perform, Miles was able to play (remarkably well!) but struggled to speak while receiving his award, and Christie was allowed to attend wearing her red dress (she is a supermodel, she definitely stood out and looked fabulous).

As for Paul McCartney, some serious help was needed to get him to the theater, including speeding him through the airport, hiring a helicopter, and flying him from the airport to the roof of the theater (which didn’t have a proper landing area). I was told the Governor of California had to be involved to speed the airport situation. Paul ran on stage just as Meryl Streep finished the tribute to him and gave the introduction. He was able to accept the award and give an excellent acceptance speech (which you can see on YouTube) but decided to pass on singing the scheduled “Hey Jude”. I was disappointed to miss my chance to perform with Paul McCartney, but he did appear to be a nice and down to earth person. On the plus side, I was able to perform with some amazing musicians that night, including Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder!

BB: You performed as a substitute cellist with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra during the 1987-1988 season. Tell us about this.

I really enjoyed the opportunity to play cello with the Toronto Symphony. They were (and continue to be) a terrific orchestra. I got to play a lot of great repertoire and work with amazing conductors and soloists.

I will share a few stand out experiences. I was really blown away by pianist Shura Cherkassky. He was 78, short and non-assuming. He played Tchaikovsky’s 2nd Piano Concerto and he made it look effortless. There were times when the piano had to play over the full orchestra playing full tilt. Shura had no problem blasting through the orchestra. There were other times when he played so softly, you could barely hear it, but there was still an incredible beauty of sound. Besides the impressive technical skills, the musicality of the playing was truly moving.

I was very excited to be able to play for Michael Tilson Thomas, who had recently started his position as principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra (UK). Michael was conducting Mahler’s 7th Symphony for the first time. This is a tough symphony to conduct and play. Michael was wonderful to work for, but during the first performance, he got lost and gave a giant cutoff one bar before it was supposed to happen. The orchestra kept playing for the bar and then stopped. Michael’s expression showed something like “Oops”. He quickly recovered and the rest of the performance was brilliant. The subsequent performances were perfect. At the time, I was surprised. After thinking about it, my bet was Michael was so focused on giving an expressive performance, it allowed him to lose track of a technical element of conducting. As a conductor myself, I know it is easy to get wrapped up in the music. Classical musicians regularly have to balance the expressive/emotional side of music with the technical demands of the artform.

I played several concerts with Sir Andrew Davis, who was in his final year as music director of the TSO. Besides being a wonderful musician, he knew how to affectively lead and inspire his players.

He showed his enthusiasm for the music and had a friendly disposition; I was a big fan. As well as performing concerts, I had the opportunity to record the album “Chaconne” with Sir Andrew. This featured violist Rivka Golani and included Canadian composer Michael Colgrass’ Chaconne for viola and orchestra (a wonderful composition!). Rivka’s enthusiasm and passion for this project was impressive.

BB: What made you change your career, from cellist to teacher, composer, conductor and music producer?

I met my wife in a summer music festival in Siena, Italy in 1982. Kaye, a clarinetist, lived in southern Ontario. We fell in love, had a long-distance relationship, decided to get married and decided to be based in Canada. I had enjoyed my Hollywood years, but I didn’t want to make working there my life’s work. In 1985, we married, and I emigrated to Canada. Between 1985 and 1990, I split my time between Burlington and Los Angeles. I wasn’t getting full time work as a cellist in Canada and I was still being offered work in LA. There were musical highlights during this period, but also some challenges and disappointments. I auditioned for a full-time position with the TSO twice, got into the finals, but didn’t get the job. In 1989, I began to experience some hand, arm and shoulder problems, as many musicians do. I applied for treatment at the first Musician’s Clinic, in Hamilton, but there was a 6-month waiting period. This was a time of self-reflection for my music career. I felt I should have a backup plan and applied to Teacher’s College and was accepted into the program at the University of Toronto. I wasn’t planning on becoming a teacher, but I ended up getting hooked. I started teaching for the Toronto District School Board and then was hired to teach at the University of Toronto Schools. I am now retired from teaching, but I loved my teaching career. The opportunity to teach students through music and share my love of music proved to be a meaningful career opportunity for me.

For my first teaching position, I was hired at Oakwood C.I, which had a strong music program, and had an excellent advanced orchestra. I was asked to be the conductor. As such, I had to learn how to conduct, which was a welcome challenge. I had the opportunity to conduct works like Beethoven’s 5th Symphony and Elgar’s Enigma Variations for the first time.

I thought about composing as a teenager, but with balancing school and playing the cello, there wasn’t much time. I also thought I didn’t have the talent for it. With teaching came summer vacations. I started to compose at this point in my life, with no expectation of going anywhere with it. After 2 years of full-time teaching, I decided to go half time and pursue composition studies at the University of Toronto, which had and continues to have, an exceptional program. I also took private composition lessons with Alexander (Sasha) Rapoport, at the Royal Conservatory of Music. I am thankful to my wife for supporting my decision to go back to school to study. I am also thankful for my education, including my professors at UofT and Sasha at the RCM, which provided the skills I needed to be a composer. Upon graduation, I started getting opportunities as a professional composer. I was thrilled! A couple of years later, I started to be invited to conduct my music with orchestras. Because of all my recording experience and connections to people in the industry, I was also asked to serve as a producer on some classical music albums. I was and continue to be thankful for all these experiences to teach, compose, conduct and produce. Presently, I am enjoying being a full-time musician again.

BB: As a former music teacher, do you know how to play all the instruments in a string or wind ensemble? Which ones do you still know how to play, and which ones are your favourite? I saw an example of you playing cello on youtube.

The cello is the only instrument that I can play at a professional level. That said, I have been able to use those skills to learn the fundamental techniques of the violin, viola and bass. There are differences, but there is a fair amount of crossover too. In middle school, I played some trombone in my school band, and in high school I studied some French horn with a friend for fun. When I decided to become a high school music teacher, I took lessons from family members and friends on the various wind instruments, so I would have the skills needed to effectively teach wind classes. Three years into my teaching career, I was transferred to Monarch Park C.I., where I was assigned to teach vocal music. I studied how to sing, and how to teach it.

I was unusual in that I never taught a non-music class during my career, though I was qualified to teach history (and I love history). Whatever type of music class, or whoever I taught, I worked hard to be the best teacher I could be. I really cared for and respected my students, so it was important to me to have the skills to properly do my job.

BB: How did you become the music director of the Scarborough Philharmonic Orchestra?

I first attended a SPO concert when my wife, clarinetist Kaye Royer, was hired to be an extra player. After a few years, she auditioned and became the principal clarinet. A few years later, the SPO had a composition contest, and I entered. I didn’t win, but a member of the committee told me my music was viewed quite positively.

A couple of years later, I was invited to become the composer-in-residence, a post I held for 3 years. A couple more years passed, and the orchestra was struggling through some hard times. They were in debt, their conductor resigned, and they had to let go of their general manager. They were close to calling it quits. I saw the president of the board at a concert and asked how it was going. I knew the SPO’s Toronto Arts Council application was coming due and I was wondering what was going to happen with their planning for the next season. Since nothing was being done, I offered to help write the grant. This led me to help with organizing the following season, including finding guest conductors. The board suggested I conduct one of the concerts. After this season was completed, the leading contenders found jobs outside of the GTA. I was asked to become the new music director. At the time I wasn’t pushing for the position because I had a very busy schedule, due to teaching and composing. I thought about it and decided I would try it for a couple of years. I am presently in my 16th year as music director.

BB: You were a music teacher at UTS. Working with a community orchestra, you are often a teacher or mentor to your ensemble. You have also conducted professional orchestras. Please reflect on your vision of how to be a conductor.

I think a conductor should work to respect, to encourage, to collaborate with, and to inspire their orchestra. This is easier said than done. As the leader, your emotional state can affect your orchestra. If you are feeling stressed or frustrated, you will probably make your players feel the same. If you can show enthusiasm, stay relaxed, provide positive feedback, create a collaborative relationship with your players, and take other proactive steps, this can go a long way in creating a fruitful and positive work environment.

If the orchestra players are feeling good, then the conductor can productively work on making music. There are two parts, one is technical and the other is musical. As for the technical, the conductor needs to be able to evaluate what the players can and cannot do. In any ensemble, youth, community or even pro, there is going to be a range of skill levels. The conductor needs to figure out what will be the most fruitful and productive use of rehearsal time. What items are essential for getting to the best possible performance?

There is a difference between working with pros vs. students and non-pro community players. Because pros have the training and experience, they know what is needed to play successfully in an orchestra. With students and non-pros, they need help for them to play their best. As such, the conductor needs to work on certain technical issues, that wouldn’t be an issue for a pro-orchestra.

As for the musical/interpretative element of conducting, there is also going to be a range of opinions on how the music should be interpreted. With student groups, differing opinions will usually be less of an issue. With pro players, who have a lot of experience and expertise, this becomes a bigger issue. However, if a conductor can get the respect of the orchestra, the players will usually support a conductor’s point of view, even if they don’t totally agree with it.

BB: During the pandemic, the SPO worked on musical projects that ended up bringing change and recognition to your organization. What did you do?

During the pandemic, it was difficult for orchestras to rehearse and perform. A lot of orchestras moved to online activities or just took a break. The SPO realized that we had the opportunity to improve our organization. Our online presence wasn’t very good, so we worked to reach as many people as possible. We decided to create the SPO Great Music Podcast, create music videos for YouTube and produce commercial albums. Most of the music would feature Canadian composers. Luckily for our organization, we had people in our community with experience in the recording and film industry.

The podcast series had interesting episodes with distinguished guest professors and musicians. We had top experts on Hollywood cartoon music, the history of pandemics and music, and the music that Shakespeare himself used for his plays. While we put a lot of effort into the series, it didn’t attract the audience we hoped for. On the other hand, our YouTube videos did quite well, with the number of views going from around 150 per year, to over 100,000 in one year. As for commercial recording, the SPO was able to develop a relationship with the Toronto based record label, Akashic Rekords, with worldwide distribution by the Universal Music Group. Our first album, Journey Through Night, featured the SPO’s ensemble-in-residence, the Odin Quartet.

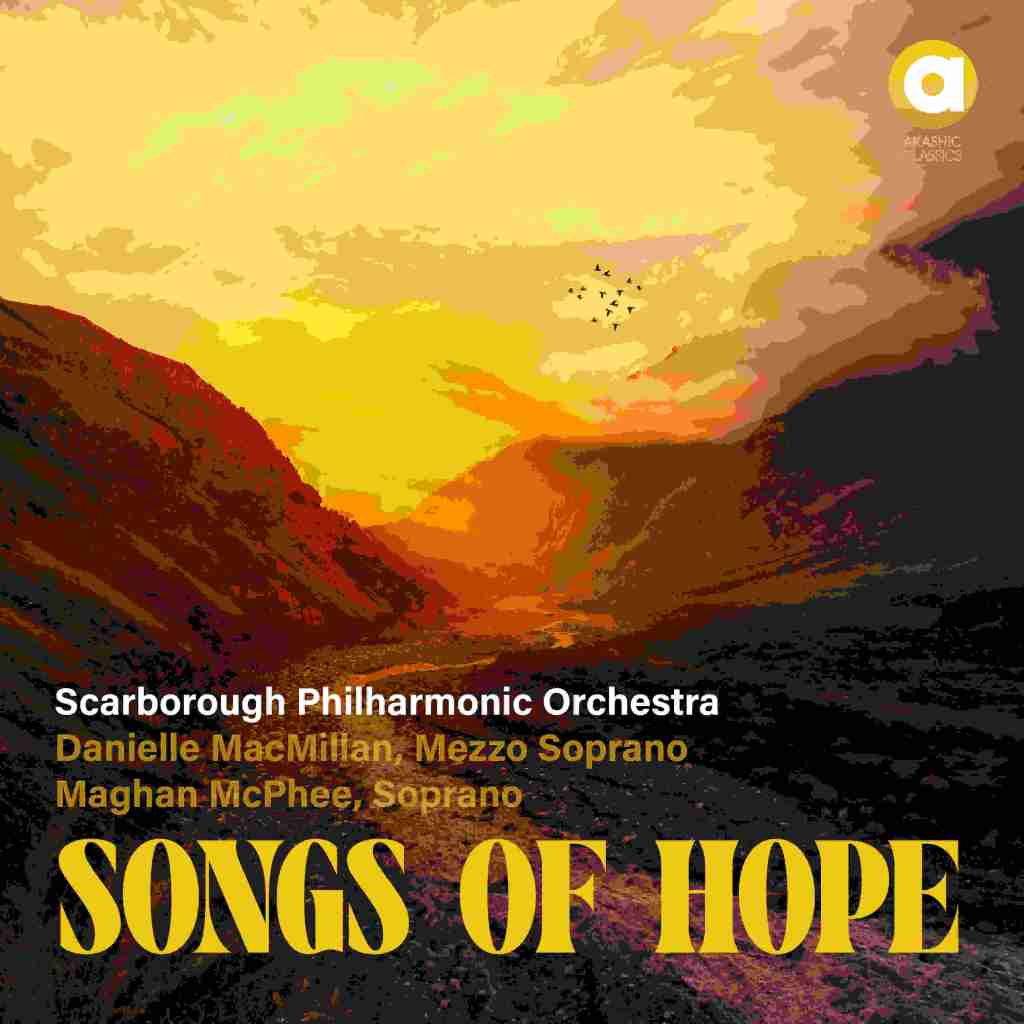

Our most recent, Songs of Hope, features mezzo soprano Danielle MacMillan, soprano Maghan McPhee, and an ensemble of 8 musicians. To date, the SPO has released 10 albums, 8 of which have 100% music by Canadian composers. The response to our albums has resulted in a significant number of people from around the world listening to Canadian performers and composers. As well, the SPO produced Musical Angels, a short film by filmmaker Saul Pincus, with music by me, performed by the Odin Quartet. To date, Musical Angels has been selected by 17 film festivals in 8 countries, and has won awards in Rome, Florence, Mannheim, and Buenos Aires.

Due to our online work, the SPO was awarded the Canadian Music Centre’s John Beckwith Award (for work to promote Canadian music), was selected to be one of four orchestras featured in Orchestra Canada’s resource, Online Audiences Toolkit, and helped us, for the first time, to receive grants from the Canada Council. All of this has raised our presence in the musical community and is helping our organization grow and develop. The SPO is continuing to post videos to YouTube and to produce commercial albums (we have four in production).

BB: I am a big fan of film music, indeed I used to teach a course in it, because the demand and interest is steadily growing. Tell us about the value of programming film music.

Due to widespread interest in movies, I think film music is a valuable tool for keeping orchestras relevant to contemporary audiences. As well, classical music needs new repertoire to continue as a living and thriving artform. Fim music, along with new classically composed symphonic music (and other types of music), helps orchestras bring in audiences and keep the artform alive.

I would like to share a little history here. When I started my career in the 1980s, film music was rarely performed by orchestras. I regularly heard symphony players and university professors dismiss film music. I think the criticism came from the point of view that film music had a different primary purpose, that of serving visual images. Symphonic music is geared to having the audience just focus on the music itself. Film music has come to be seen as a valid form of music for the concert hall. It is composed to touch the audience emotionally, and to help with this, the music often makes great use of the orchestra (e.g. the music of John Williams and others).

It has been interesting to see the situation change over the decades, to the point where film music is now an important part of standard symphonic repertoire.

BB: I know you as a champion of Canadian composers, which seems especially precious at a time when people are being urged to “shop Canadian”. Tell us more.

The arts are a valuable way a country can define itself. Artists help us understand who we are as people, a society, and a country. I think it is great that in Canada that we have arts councils who promote and fund the work of Canadian composers as part of this bigger cultural initiative. Because of this, it has helped our country develop quite a strong, large and diverse group of composers. So to speak, we punch above our weight as a country.

The SPO has a long history of supporting Canadian composers and having a composer-in-residence program. At present, there are a number of people in the SPO community that believe that supporting Canadian composers is important, and this includes my passion for it as well. As such, the SPO makes it a priority to program Canadian music.

As for SPO recordings, it just makes sense. Does the musical world need another recording of Beethoven or Brahms by the SPO? The SPO decided that we can and should support Canadian composers (who deserve to be heard by a worldwide audience) and do something of value for Scarborough and the greater Canadian musical community. At a time when Canadians are rallying around our country, listening to Canadian music is something we can all do and feel proud of.

Note: all the SPO albums can be found online and listened to for free!

BB: do you have any ideas about reforming / modernizing classical music culture to better align with modern audiences

This is a tricky question. I don’t think there is a one solution that fits all, but there are a number of solutions for different orchestras and situations.

To me, classical musicians have to stay connected to the society around them. The key is to be sensitive to your audience, be willing to try new things, and then make changes. Organizations who evolve and change, generally do well. Those who refuse to change, generally struggle and have more problems.

BB: Do you have any upcoming projects / shows / workshops you might want to mention / promote?

I always enjoy conducting the Scarborough Philharmonic. We have wonderful players who perform with a high level of skill, musicality and enthusiasm. Audiences are also enthusiastic and usually give us a standing ovation.

On March 22, the SPO is celebrating our 45th anniversary by performing Beethoven’s 9th Symphony (Ode to Joy) and Bruckner’s Te Deum with the Toronto Choral Society. On May 3, we are performing Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer (featuring mezzo soprano Danielle MacMillan) and Borodin’s 2nd Symphony. Also included are short works by Ravel, and two pieces by the wonderful new generation Canadian composers, Rachel McFarlane and Shreya Jha.

I would like to mention a SPO album featuring my music, Night Star, Chamber Music by Ronald Royer. I am thankful for this opportunity to have had my music recorded.

BB: Of your own compositions what is your favourite?

I don’t have a favourite composition. Every piece I have composed has meaning to me. I would like to talk about two works composed recently that have special meaning for me. The Rhapsody Concerto, for Viola and Orchestra (2023), was composed for Máté Szücs, Hungarian soloist and former principal violist for the Berlin Philharmonic. Máté first performed two of my compositions when he was concertizing in Southern Ontario during the fall of 2019.

He also recorded my Mirage quintet during his visit, and then recorded my Sarabande, from In Memory J.S. Bach, for Viola and Piano in Budapest in 2020. After this, he asked if I would write a concerto for him, wanting a showpiece for the viola. To date, the concerto has been performed by the SPO, the Peterborough Symphony and the PRIMA Festival Orchestra in Powell River, BC. At the end of each performance, the audience immediately stood and cheered. As a composer, it was gratifying to have such an amazing soloist perform my music and to see audiences react in such a positive way.

When I started college in the late 1970’s, I took a world literature class, which included reading Dante’s Divine Comedy. I hadn’t started composing yet, but after reading the book, I decided that I would like the challenge of composing music inspired by this epic poem. In 2024, I finally composed Women of Dante’s Divine Comedy for mezzo soprano Danielle MacMillan, and an ensemble of 8 players from the SPO. This was for the Songs of Hope project. The challenge of composing music for a work that went from hell to purgatory to heaven was intriguing. I have thought about this project for decades and finally the right opportunity came to compose it. This was one of those “bucket list” projects for me.

BB: Do you have any closing thoughts?

As a teenager, I thought I would spend my career as a professional cellist. My family of musicians was in agreement. However, I had one uncle, Mario DiTullio, who disagreed. He said “Ron will need more than the cello to satisfy him”. When I started to have hand and arm problems in 1989, it caused me to reflect on my music career. I realized that I needed more than the cello to feel satisfied as a musician. I went to Teacher’s College, studied composition and conducting and transformed my career. A few years down the road, I produced my first album, for the Toronto Sinfonietta. I feel fortunate that I have been able to experience music from all different perspectives. It is interesting to note that most players, conductors, composers, administrators, and producers all view music and the music business a little differently.

My music and teaching careers have brought me many amazing experiences, but it has also brought a number of challenges. I have focused on the positives in this interview. I think the point of my interview is to stay positive, keep a sense of humour, work hard, get along with people, be open to opportunities, and be willing to make changes. We don’t know what life will bring, and it will bring challenges, but keeping a positive can-do mindset helps.

I want to thank you Leslie, for inviting me to do this interview.

Upcoming with the Scarborough Philharmonic:

March 18, 2:00 pm – 5:00 pm: US-CAN Film-scoring Challenge

A showcase and workshop (click for info)

Saturday March 22:

JOY! (click for info)

Saturday May 3rd: Journeys (click for info)

Great interview Ron!

What a great interview. I had to pleasure to meet Ron recently and was impressed by his sincerity, thoughtfulness, kindness, and positive outlook on life and music. That all shines through in this interview. I am so impressed by the way he managed to turn the fate of the SPO around, and the work that he and the orchestra are doing now. Keep up the great work, Ron; what you are doing is so important for the musical culture of the GTA.

Ron is quintessentially Canadian, so humble. It was a challenge getting him to talk about himself. I think his life story would make a great book if we could encourage him to tell more stories. Thanks for the kind words.