I want to explain where I’m coming from, as I review the second of three books from Sky Gilbert about William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare Lied appeared in 2024, while Shakespeare Beyond Science came out in 2020. My response this time (over the past year) is an even more extreme form of what happened last time. Here’s what I said in 2020 (click here to see the full 2020 review):

I’ve been dancing around this one for quite awhile, hesitant about the review because I am in awe of the book. Nobody expects me to be brilliant even if the book has put me in touch with a desire to be immortal, to make an impact. Gilbert’s book deserves to be read, deserves to be influential. While Gilbert hasn’t been a professor for very long (he was still in grad school when I was there not so long ago), he’s doing great things.

As it has almost been a year since I began reading & re-reading Shakespeare Lied that effect applies even more. This has been a very introspective year for me, a caregiver and a son mourning the passing of his aged mom, pondering the meaning of life, pondering meaning itself.

Sometimes a book you read can totally colour your experience, changing the way you see and hear everything. That’s one of the reasons we read. A book may teach you how to unravel your puzzles, even if reading may also lead you into a deeper labyrinth than before. When the world goes to shit, whether you’re looking for a solution or you want to find a really good umbrella, a place to shelter, books do that better than almost any drug or altered reality I know. Music usually is my go – to, but first, I need to look at the single book that had the biggest impact on my 2024, that I continue to re-read as I try to do it justice.

And yes this may be a cautionary tale for those who want me to help promote their work, as I take it very seriously. I will read and re-read a book because I don’t want to just do a book report. I want to understand.

I normally don’t like spoilers, as the experience of the story or the unfolding of the argument are a kind of magic. I feel it’s sacrilege when a reviewer fills their review with the best lines of a comedy or tells you the outcome of a plot and so for example my recent review of Heratio tells you next to nothing because I aim to be spoiler free. But I don’t think I will be ruining anything if I give you the central conceit of Sky Gilbert’s latest book: Shakespeare Lied. Lately this book and its unique lens has become a kind of subtext for everything I see and by implication, everything I’m writing lately.

Sky’s book is a filter through which I’m seeing everything right now. He asks a question that I keep coming back to: “What, after all, is one to believe?“

I hear that in my head not so much as a mantra, but as a reminder. We’re lost in the forest with Hansel & Gretel, not knowing which way to turn.

In 2024 I watched JD Vance and Tim Walz debate through the lens of Sky’s question, impressed by the fluidity of Vance’s delivery even though he lies like a rug, if you take my meaning. But I am not going to go off on the tangent of asking “what is truth” as though I were Pontius Pilate interrogating Jesus. I’m less interested in what fact-checker Daniel Dale had to say than I am in performances, rhetoric, portrayals and (especially apt for politics) reception. What are we to believe, and what is the consensus? We’re as mistaken as Chuck Schumer and the Democrats in how we approach discourse, if we get hung up on questions of truth & procedure, missing the point. And indeed I think it’s worth noting that Daniel Dale was ultimately flummoxed by JD Vance’s running mate, a man who has taken questions of truth and hair to a whole new level. When we zero in too closely on the factoids we miss the forest for the hair.

Or the trees.

Sky’s book was very helpful when I wrote about Canadian Stage’s 1939, foregrounding the play’s colliding performance styles, layers of meaning on top of other meanings. I have a new appreciation for the meta-theatre I see all around us in media. I alluded to General Leslie (Dick) Rhodes, key player in the development of the American nuclear arsenal, a devout Presbyterian from the family of a Chaplain that I mentioned in my review of John Elford’s Our Hearts Were Strangely Lukewarm. Mere questions of truth miss the performative b.s. of genocidal Christians who have no trouble sleeping at night: because they’ve been blessed and absolved.

I could go on with more examples, such as Tafelmusik led by Rachel Podger and the Pictures concert of TSO all through the rose-coloured glasses of Gilbert’s ideas. The point is, Sky isn’t just talking about Shakespeare. Or maybe I should put it in context with his previous book on the subject, Shakespeare Beyond Science: When Poetry was the World (2020).

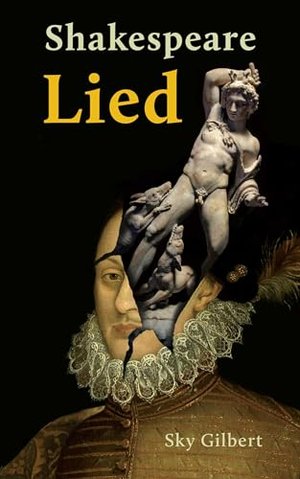

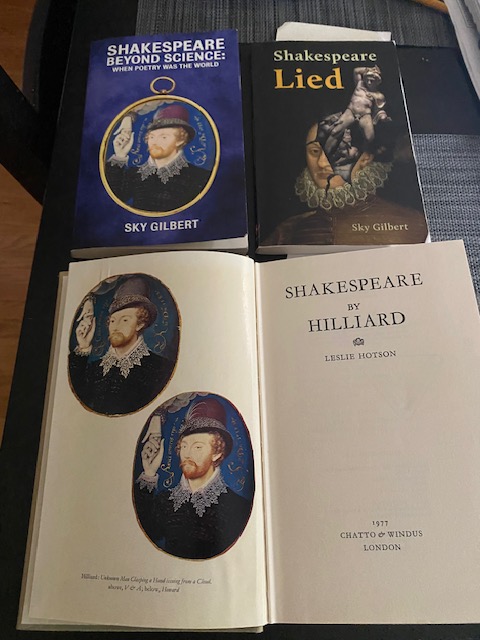

The first book is gentler and more even-handed, while the new book reads like a polemic. There’s an intensity to it beginning with the cover, showing us Acteon, attacked by his hounds, as he bursts through Shakespeare’s head.

I can’t help noticing that Sky used a big long title last time and this time a tiny one. Speaking of filters and influences, I can’t help thinking that — like Daniel Dale’s orange nemesis–Sky is trying to simplify things for those who didn’t get it the first time. But don’t get me wrong, the new book doesn’t dumb it down. Far from it. The first book was more Shakespearean in its flowery approach to scholarship. In fact I think he was very gentle and careful in his diction last time as though he were giving us the undergraduate version, while this one moves more quickly and passionately, like a grad school version.

We’re in the discursive realm of sequels, where the author presupposes a lot more, daring us to follow him as any good lecturer does. Graduate school assumes you saw the first film and so will know about the relationships, the politics, the objectives of each character. We get to the point faster which makes some sentences more electric and even acerbic.

The first book is great preparation for this new book. And they make a fascinating study as a pair. I can’t help looking at 2024’s foray as a continuation of the 2020 study.

But maybe the real difference is that this time it’s personal. I don’t know enough about the background to comment, except to frame this for you, using the words in Sky’s prologue.

During Buddies’ 40th anniversary season, I was delighted when Artistic Director Evalyn Parry announced a reading of my 1986 hit play Drag Queens in Outer Space. A week before the reading I wrote a controversial poem for my blog. I received an email from Evalyn Parry saying the ‘community’ was up in arms about my poem. I politely suggested Evalyn ignore the hysteria. In a return email she stated that due to the offensive nature of my poem, the reading of my play would be cancelled. I was thus forced to remove myself from any association with the company that I founded many years ago. (Shakespeare Lied p11)

We don’t get to read the poem in question so the controversy is a black box, something mysterious and unknown to the reader. I did some searching, looking for something from that time, a clue about the poem, but came up empty… Perhaps we can set that question aside for the moment.

The next thing Sky talks about in his book didn’t seem terribly important, namely his viewpoint about the way he was being read: a discussion of form & rhetoric, not unlike what we saw in the first Shakespeare book, but now pointed squarely at writing of the present century. I’m mentioning this in the interest of being comprehensive & complete, not because I think it’s important. I don’t think we usually need to know what was going on in an artist’s life when they made their creation. Yes Sky sounds a bit angrier in this book than he did last time, even if Shakespeare Beyond Science came out in 2020, long after the controversies I’m alluding to.

As I ponder the two books in August 2025, I’m struck by a contrast, that may be a reflection of where I am at rather than an accurate picture of the two books. But one book filled me with inspiration, one throws me back, hesitant and questioning what lies beneath. The first book suggests I can get closer, get to know something about Shakespeare. The second says not so fast, maybe he’s not knowable, maybe we don’t want to proceed because: our hearts are bruised and even broken. We’re told just a bit of that mystery I spoke of, about poetry & art, from a mysterious community of secrets, concealed identity, performative virtues, backstabbing, conspiracy, false loyalty. It may be dark but it has the ring of truth & authenticity because of its passionate delivery, something less than full out Shakespearean histrionics. Having just seen the latest meta-Shakespearean show (Heratio) I hesitate to try to distinguish between what’s imaginary and what is genuine. And yes I know, the way that second book seems to parallel a zeitgeist full of lies & fakery makes me wonder: is it the book or is it me? Am I watching CP24 or CNN too much? The books are both mirrors, and maybe I need to be careful not to write a book review that sounds like I am talking about myself and my own self-doubt, my own awareness of mortality.

As I pondered the two books and the many sources Sky acknowledges, I knew what lay ahead, because at the end of the second book Sky’s bio says that he’s working on another Shakespeare book tentatively titled “Shakespeare’s Effeminacy”, the concluding volume of a trilogy about the identity of Edward de Vere.

In my reflections, knowing another book was coming I wandered off into the sources, the alternative readings of Shakespeare and his life, competing theories about authorship. It’s a huge industry of course. Let me suggest further reading if you would like to discover more, as I confess my own conflicts & quandaries on the topic(s).

In his first book Sky pointed us towards the research from Canadian scholar Leslie Hotson, a writer from a previous generation, writing about the Hilliard miniature in his 1977 book Shakespeare by Hilliard.

When I consider the way Hotson writes, it’s a trip back in time, less to the era of Shakespeare as to a time of arcane & obscure criticism allegedly in the service of truth and clarity. The book is a labyrinth. While I may have complained at the density of the discourse Sky offers up in his second book, compared to the accessible language of the first, they are both worlds away from Hotson, whose prose suggests something secret & obscure as hieroglyphics or runes inside a musty tomb, as Hotson gives us a musty tome, and I have to give an example to justify such extreme language. In his first book on page 57 Sky says the following:

<<As Hotson tells us (quoting Littleton) , Apollo was associated with oracles and messages that were riddling or “oblique”. This means he was prone to “speaking ambiguously, so that he can be taken divers ways”>> (Shakespeare Beyond Science 57)

That’s Sky. Here’s a sample of Hotson, and it won’t matter where I start, because it’s all a miles-long thread running through that forest I spoke of:

Randolph’s wry-legged god is his translation of Ariostophanes’ term Loxias, which Henry Fielding’s version of the Plutus gives us that oblique deity. For the explanation we turn to Littleton: ‘Apollo was called Loxias; who in his replies was loxos, that is, oblique, and speaking ambiguously, so that we may be taken divers ways.’ (Shakespeare by Hilliard 96 )

So of course, in his book about oblique or riddling messages, Hotson is poking oh so slowly oh so carefully at the tiny relic Sky put on the cover of his first book, spending 200+ pages ultimately telling us a tiny bit about a tiny thing. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not complaining. But I feel a bit like an explorer in that forest, now peering into a deep dark well, afraid I will fall in.

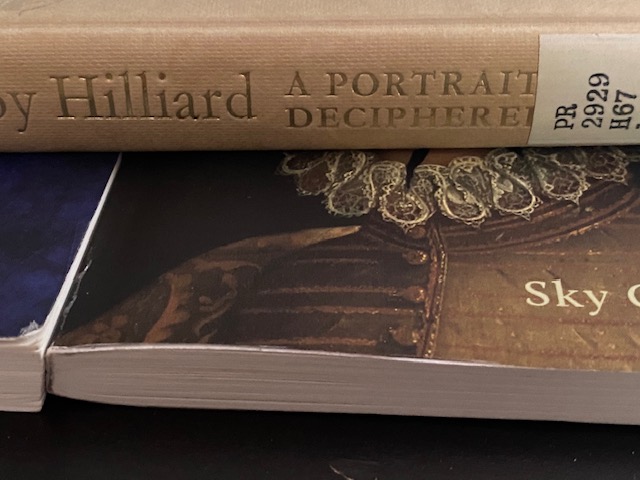

The book’s title as it appears on the spine:

“Shakespeare by Hilliard A PORTRAIT DECIPHERED”

While that sub-title is on the spine of the book I couldn’t find anywhere inside the book nor anywhere in the bibliographic record when I look on the UTL website. Hilliard and perhaps Apollo himself would approve of this oblique approach, presumably true to what Hotson wanted.

So as I wander about inside that well (yes I fell in), there are other books and theories that I am simultaneously pondering. Hotson also wrote about Mr WH, a person of some interest in the conversations about Shakespeare and the sonnets.

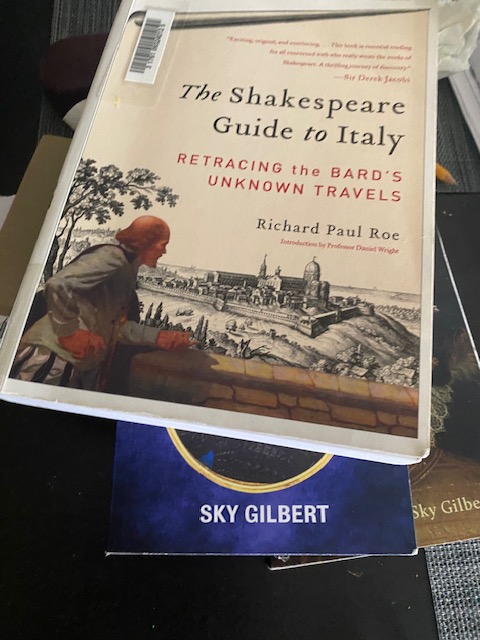

A more recent book complicates the conversation, namely Richard Paul Roe’s 2011 Shakespeare Guide to Italy: Retracing the Bard’s Unknown Travels. I was stunned reading so many explanations that correspond to lines in plays that previously made little or no sense. The book offers connections in many of Shakespeare’s plays, set in places with Italian or Mediterranean place names, drilling down on tiny details over and over again.

I will look in Sky’s third book for some mention of Roe’s analyses. Whatever version of Shakespeare’s life you want to write must reckon with Roe’s conclusions.

Feeling lost I searched and found even more confusion. Paul Streitz wrote Oxford: Son of Queen Elizabeth I, a book that I have to chase down, seemingly arguing many of the same things Sky’s books argue, again speaking of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford as the alias or perhaps the true identity of William Shakespeare. Perhaps this is old news? I had not heard this version before, with Elizabeth the Queen in a starring role.

Sky makes no mention of Streitz. I feel a bit perplexed to see that neither Streitz nor Hotson are cited in the back of Roe’s book, which is amazing in a bibliography that’s over 10 pages long. In the tiny Epilogue of his study, Roe calls attention to a disconnect between accepted scholarship & his observations, suggesting that his goal was to “revisit these orthodox beliefs and contrast them for their accuracy with the actual words of the English playwright” (Roe 297).

Maybe in the next generation someone will pull it all together, make sense of the different theories.

I’m reminded of Sky’s title and a year spent observing the lies all around us. Yes there are so many books about Shakespeare that I suppose you dear reader and I could miss a few books. But a scholar studying Shakespeare’s life? That seems hard to believe, even if he meant to ignore or dismiss their work.

Let me quote Sky again even as I admit I am lost. “What, after all, is one to believe?“

So I am waiting for Sky’s concluding book, as I plan to delve deeper into Hotson, Streitz, Roe and yes, Shakespeare.