When I started reading John Holland’s new book, I didn’t expect it to be more than a study of a composer and his operas.

That modest goal would already be significant, considering the cognitive dissonance I feel whenever the plural phrase “Dvořák’s operas” reaches my ear or eye. I glibly think I know Antonín Dvořák, one of the most important composers of his time, composer of wonderful symphonies and amazing piano music. I admit that I know his life only superficially, his travels in America resulting in remarkable music, his connection to Brahms, which I only know in the most superficial terms. Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances are among my favorite pieces of music, as they got me through the worst of the pandemic, meaning a two-handed arrangement of his Op 46 and 72. I’m smitten with the first set of eight, still figuring out the second set. I am sometimes puzzled that he isn’t better known, but that’s just one of the mysteries that begins to be answered by John’s study.

I was frankly gob-smacked reading John’s book, not just with the discovery that Dvořák composed ten operas, but that except for Rusalka all of them are out of print. How could that be? When I go to the Edward Johnson Building Music Library at the University of Toronto, admittedly one of the greatest collections anywhere in North America, I am repeatedly spoiled by the excellence of their comprehensive collection, whether among popular composers (Philip Glass’s Akhnaten or Songs of Liquid Days) or more obscure treasures such as the piano vocal score of Camille Erlanger’s Aphrodite, autographed by the composer himself.

So while I can find all of Mozart’s or Verdi’s scores, multiple copies of Puccini or Wagner operatic scores, can find a piano version of Mahler’s 5th Symphony or Liszt’s transcriptions of Beethoven and Wagner, my mind boggles to think that John Holland himself has a better collection than my beloved music library. I don’t mean to single out the EJB, as John’s research has enabled him to assemble a considerable library of the scores that, if not the most comprehensive in the world, is certainly the biggest in North America. You want proof that Holland is an expert? Let’s start there! Sigh, I was looking forward to grabbing the score of Jacobin to play through it at my piano and maybe sing some parts, in preparation for the upcoming production: but it’s out of print. Or to explore his other scores, the way I’ve been able to do with the early operas of Mozart or Wagner or Verdi.

But I can’t do that obviously.

It’s not just puzzling that the works of a great composer can’t be found. I find this quite upsetting, especially with the help of Holland’s book. I don’t know if he meant to light a fire under me, but the book is quite disturbing in the best way, exploring the context in order to raise questions and inspire curiosity.

How could this be, and how did this happen? That’s what Holland’s book addresses.

I was trying to put Holland’s work into context. I’ve barely begun that, really. Let’s talk about history for a moment. When I started reading The Lost Tradition of Dvořák’s operas I was surprised at how much history is included, how much background we’re given before Dvořák even appears in Chapter Four. Chapter One is really about John Holland and his experience of the phenomenon that I’ve been obsessing over, his encounter with that bizarre absence of Dvořák’s operas from the world. Please note we’re not talking about a composer who tried and failed at opera. Liszt and Mahler for instance avoided opera except as producers and conductors. Dvořák composed ten operas. And considering that opera would be the composer’s preoccupation for much of the last decade of his life (as Holland explains), it’s especially perplexing that but for Rusalka, none of them can be found in print. Maddening.

That’s why I’ve put the headline on this book review. Holland is taking a position as a scholar that is pointed and energetic. The fact I couldn’t put the book down but read its 180 or so pages in a little over 24 hours is a tip-off. I’ve been re-reading the first chapter, which reads differently after you’ve finished the book. I suggest you do the same thing, as it reads differently, retrospectively.

As a Hungarian I want to pose parallel questions, having spotted a word that grabbed me. To “Germanize” is something that may sound odd to your ear. Yet I’ve noticed this among other Europeans. It’s Georg Solti, not György Solti, nor Solti György, given that the Magyar way is to put the surname first. Franz Liszt, not Liszt Ferenc. See a pattern here? Whether we’re speaking of the great 19th century virtuoso or one of the greatest 20th century conductors, Hungarians have often used a Germanic form of their name. Indeed it prickles me a bit to think that the word “Hungarian” is itself of foreign derivation, as we call ourselves Magyar not Hungarian. The misnomer via a Latin root reminds me of other comparable names applied from abroad such as Eskimo (rather than Inuit) or Gypsy (rather than Roma), although the experience of the Magyars was far more successful, via this Germanizing tactic, than what we see from Dvořák. No wonder then that Holland embarks upon a project of cultural rebirth, seeking to breathe life into a moribund tradition. But it wasn’t just a matter of popularity.

I almost feel like I’ve seen a political thriller or a documentary history, rather than a book of musicology, disliking “spoilers” that give away plot-twists. But this is history and indeed the fiction part might be the version of the truth that we were given before. At times Holland’s book reads like activism, in its efforts to rescue Dvořák’s operas from their undeserved purgatory, where they sit waiting to be remembered and revived. Perhaps an organization such as the Canadian Institute for Czech Music can help, as CICM could promote interest in Dvořák’s operas, by helping find & publish the scores.

It can’t be a surprise to think that political questions rear their problematic heads, both from Dvořák’s time and since. I wouldn’t presume to paraphrase complex questions in this space. Operas become popular for a multitude of reasons, as most go in and out of the standard repertoire. We hear of politics in the opera world (competing visions of what opera should be) and the cultures presenting opera. In the case of Dvořák’s operas it’s not enough to speak of a loss of interest, when the operas are literally gone, out of print. Holland doesn’t go as far as to suggest a conspiracy but does show mechanisms whereby Dvořák’s operas have been discouraged, in effect suppressed when one looks at the outcome as of 2024, when only one opera can be found in print. I completely accept the validity of Holland’s historical essay, describing the contending factions and their motivations.

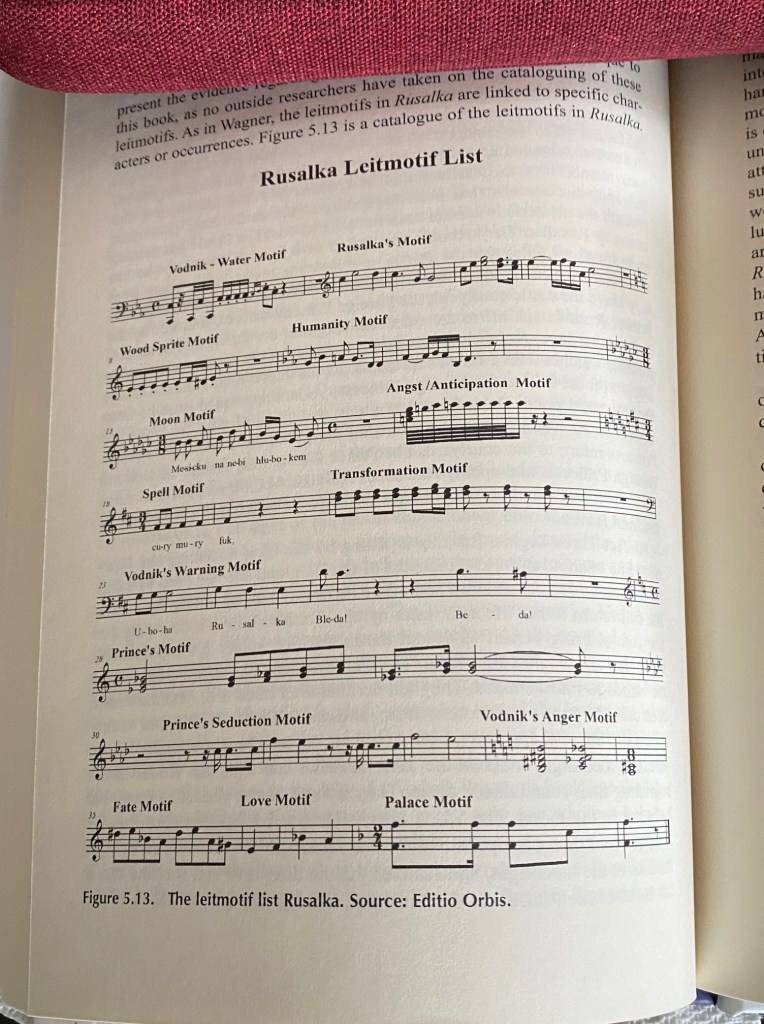

Along the way we get musicological analyses with splendid illustrations from the missing scores. There’s a chapter looking at Jacobin and Rusalka as a pair of operas that show how Dvořák reconciled himself to the two poles of operatic dramaturgy, namely the Wagnerian model and the number opera associated with Verdi. Holland even gives us a leitmotif list for Rusalka! How cool is that? As far as John knows nobody has done this before.

When I was first getting to know the Ring Cycle, it was a special thrill that the Solti recording of Das Rheingold that I got in my teens directed us to notice the leitmotifs as they appeared. And then I encountered books with different ways of understanding the themes, eventually coming to Robert Donington’s Ring and its symbols. I invoke Donington to suggest that there are higher levels of engagement with a score, that can only begin with the kind of work John is doing with Rusalka, let alone the invisible scores. At the very least John is laying groundwork for future studies, including those he may do in the years to come.

One of the issues John brings up can sometimes be a lightning rod for discussions about operatic production, namely Regietheater aka “Director’s theatre”. Our different academic pathways may be showing in the way I react to what John is saying (my graduate work was in drama, not music), although I am sympathetic. John is absolutely right to observe that in opera productions the 21st century is so far a century that belongs to the director. Indeed I must mention that in many respects John writes a history of opera, inserting Dvořák into that study, a broadly based analysis, at least until he gets to the part where he observes the challenge of Regietheater. I was amused hearing what John has to say, and confess I’ve had similar conversations including a big argument I had with a member of my committee who was outraged by the COC’s production of Semele.

In the best of these, one can still see the original through the layers. I’m again invoking Linda Hutcheon’s metaphor of the palimpsest to describe adaptation, where we see through the new surface to the older text seen beneath: or at least one would hope so. When Patrice Chereau set his opening scene of Das Rheingold in a modern river where we see a power dam rather than a pristine riverbed, we were still within shouting distance of the original, that was distorted but not harmed by the imposition of new contexts onto the old.

But it’s problematic when the text being presented is unknown. We won’t see through layers if we don’t know the original opera. John complains about a London production of Rusalka that for many was their first experience with the work, and therefore (in his view) destructive as far as the popularization of the works of Dvořák. I’m a bit more of a Darwinian, believing that popularity is a de facto phenomenon, not so very different from the phases of the moon or the weather, being largely beyond our control.

Difficult, too, is the question of opera that presents folklore and ethnic culture, in a theatre environment that seeks to be edgy or controversial. John rightly observes that maybe this is bad timing for Dvořák. I have more faith. I have seen how a Regietheater approach can sit on the fence, working with something traditional, as in Dmitri Tcherniakov’s Prince Igor at the Met, or his Bolshoi Ruslan und Ludmila. In both cases the traditional surface of the first part of the production sets up electrifying drama in the latter part of the production. I wish I knew Dvořák’s works better, to be able to speak more authoritatively but haha, nope. I am confident, though, that publishing scores and getting the chance to hear the music will work its usual magic, especially as an admirer of Dvořák and his gift for melody. Once they’ve heard it, film-makers will start inserting the music into their movies, singers will program arias or scenes into concerts, and as curiosity will grow about the operas, there will be a need to produce the works.

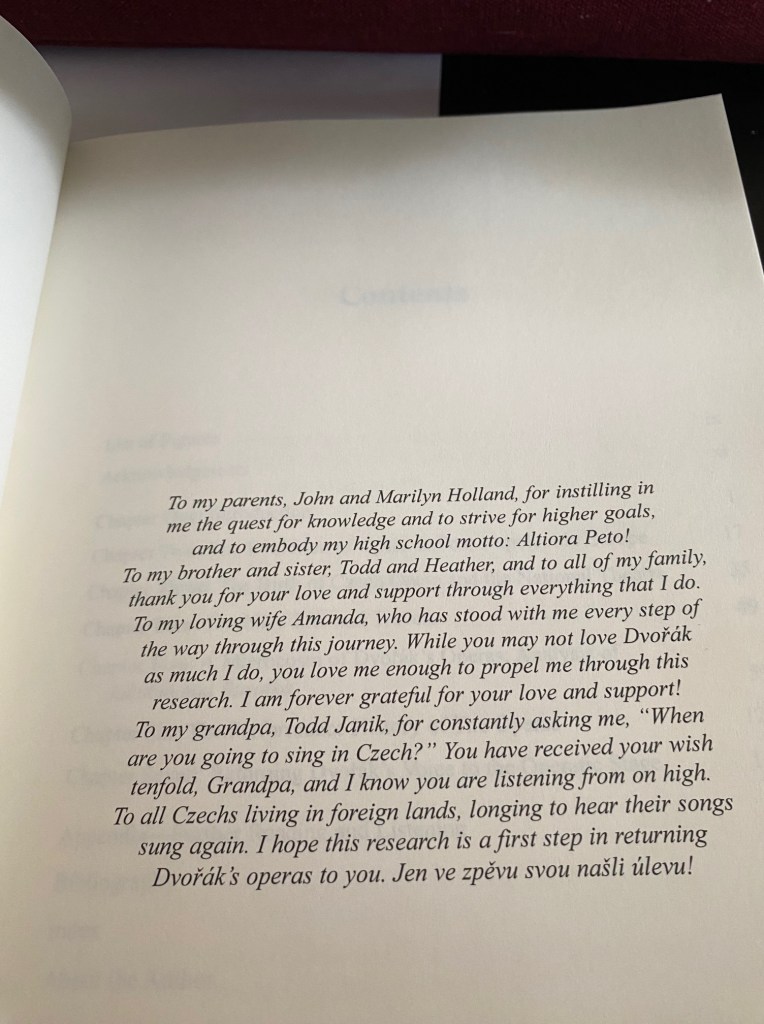

No it won’t happen overnight. But my goodness, John Holland is performing important work to make this possible. I was moved to the brink of tears reading the dedication of the book.

Pingback: Year(s) of Czech Music at the piano | barczablog