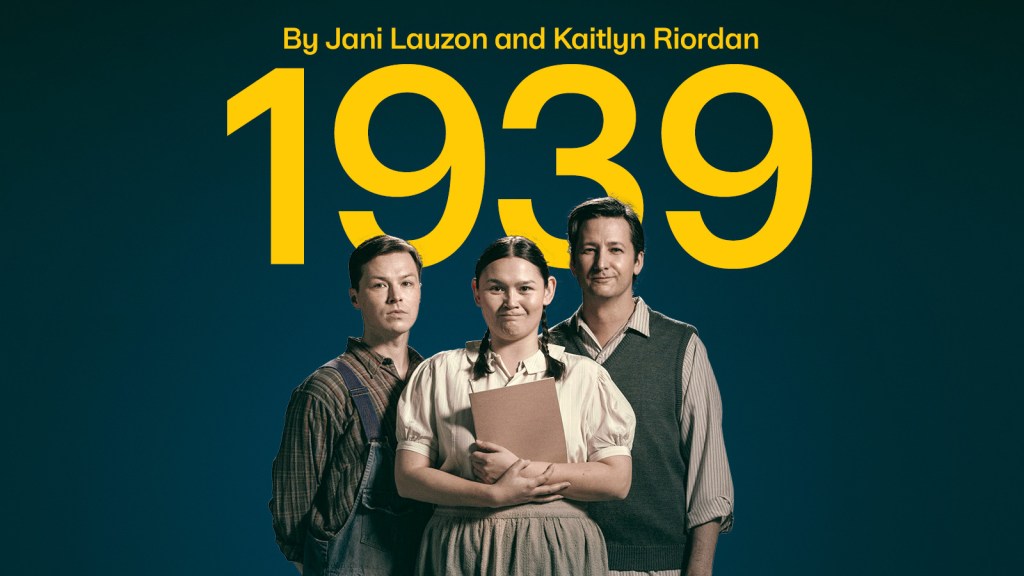

Last night I watched 1939, a recent play by Jani Lauzon and Kaitlyn Riordan at Berkeley St Theatre, a brilliant snapshot of the madness of residential schools and resilience in response. It’s a Canadian Stage and Belfry theatre joint production in association with the Stratford Festival, where 1939 had its 2022 premiere.

Imagine the presentation of a Shakespeare play by residential school students for a royal visit by the King & Queen of England in 1939. Their normal lives in school were already a performance, the lies they are forced to tell while suppressing the truths inside them. The bizarre Shakespeare project underlines the absurdity of students separated from families & culture while being imprinted with new unfamiliar Christian ideas by their teachers.

As in any first encounter with a text I’m balancing the creation of words and the performers’ creation, this time directed by Jani Lauzon, who is one of the authors. I missed seeing the piece in 2022 at Stratford, but wonder if in this incarnation it has become something new or different, deeper or perhaps lighter. I don’t know. At times we’re watching a frenetic stage full of fast moving bodies. At other times we observe a person alone in quiet reflection. At times they may struggle with language, although at times words are used playfully even if we don’t understand the words that are in an Indigenous dialect. There is so much going on, layers of meaning and action. Frequently we see words written on a blackboard, that will then be erased by Father Callum, a reminder that truthful expression is not always permitted. There is a persuasive self-assurance to this production and its cast that is irresistible, perhaps also because so many in the show are themselves Indigenous.

It was much funnier than I expected. For some such a topic may trigger overpowering emotions, and in response Canadian Stage included a gentle talk-back session for sensitive reflection afterwards, facilitated by Angel Brant, Shak Gobert and Manuel Chaves. I found that the deeper we penetrated into the story, the less I was able to laugh, although Lauzon/ Riordan did offer cheap laughs via silly costumes and fart jokes, perhaps hoping to dissipate powerful emotions. It’s barely conceivable that this be comedy, when we recall Kent Monkman’s paintings or the Truth & Reconciliation Commission, the cultural genocide to eliminate Indigenous languages & cultural practices through schools forcing children to become something they weren’t. The idea of finding comedy in residential schools is not only unexpected but a beautiful objective, perhaps a step on the pathway of reconciliation. I’m grateful for the encounter, amazed at the generosity of the performers.

It’s fascinating to watch the poignant variety of responses to Shakespeare, who at first is as completely alien as he must be to anyone reading gibberish, words they can’t understand.

While Shakespeare’s language, especially as understood through their teacher, is at first foreign and rigid, the attempts to perform Alls Well that Ends Well become a redemptive escape into something more authentic than the Christian platitudes they’ve been force-fed.

Father Callum (Nathan Howe) hopes that donors seeing the student play performance will help pay for needed repairs to the roof of their building. When a newspaper reporter (Amanda Lisman) comes to see their preparations for the royal visit, leading to a feature article publicizing their production, the project is pushed in a new direction.

Suddenly instead of the usual effort to deny their culture and to assimilate the students as Christians, Sian the teacher and director of the student production (Catherine Fitch) seeks to emphasize Indian culture, getting costumes and sets for the production. Of course these are inauthentic and cliche. At one point in rehearsal, perplexed when she discovers that no they are not all the same culture, as one is partly Cree, another Ojibwe, another Mohawk, Sian asks if there is a generic Indian that they can play. The ineffectual teachers are more sympathetic than expected.

Evelyn (Merewyn Comeau) surprises her teachers by the strength of her acting, because she channels the wisdom of her elders. Susan (Brefny Caribou) follows suit, letting the memory of a quirky uncle inspire her as the clown. In contrast, Beth (Grace Lamarche) has loyally subscribed to the instructions of her teachers, believing in the residential school promise of a better life if she learns her lessons and rejects her native heritage. When Sian encourages them to play as Indian rather than as an assimilated English Canadian, Beth is perplexed, caught in the contradictions of the school and its lies, but also aware that in her acceptance of the school’s implicit bargain, she has cut herself off from a native past to which she no longer connects.

Joseph (Richard Comeau) is Beth’s brother, a fact the teachers didn’t realize until it’s disclosed during rehearsal. Jean (John Wamsley) and Joseph, who also have parts in the play will also tell us about a hockey game with a local private school that figures prominently in the unfolding of the plot. In due course we will see the presentation of their play within a play unfold, and their decisions as to how to enact their Indian portrayals, reconciling themselves.

1939 continues at the Berkeley St Theatre until at least October 12th. I recommend that you attend, and if possible stay for the experience of the reflection space after the play.