2024 is the year of Czech Music, a celebration that’s held every decade in the year ending in 4. Speaking of ending, this year’s instalment is swiftly coming to a close, a year that saw the Canadian Opera Company present Cunning Little Vixen early in the year, and the Canadian Institute of Czech Music offer a series of concerts and operas.

I had my own little version at the piano.

But the reason I put that s in brackets–suggesting a plural rather than singular– is in recognition of how Czech music has been a staple for me, especially since COVID. When you can’t go to concerts or theatre, both because of the pandemic and as a careful caregiver avoiding infection, the solitary pursuit of music at home takes on a new significance.

When people mention Czech music they are usually thinking of Antonin Dvořák, the great symphonic and operatic composer who was a focus for a book review as well as an interview with John Holland earlier this year. Dvořák is not the only Czech composer I’m looking at in this piece but he must get the lion’s share of attention to properly reflect his importance to me, the composer who for me is most synonymous with Czech culture.

Of course Dvořák also wrote lots of piano music. Years ago I found a Dover edition collecting shorter works at the Edward Johnson Music Library (my usual resource for new discoveries) including the marvellous Humoresques and the charming Silhouettes, lots of fun.

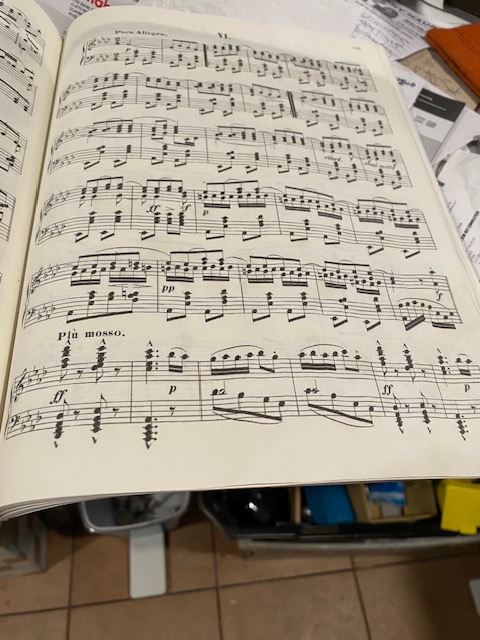

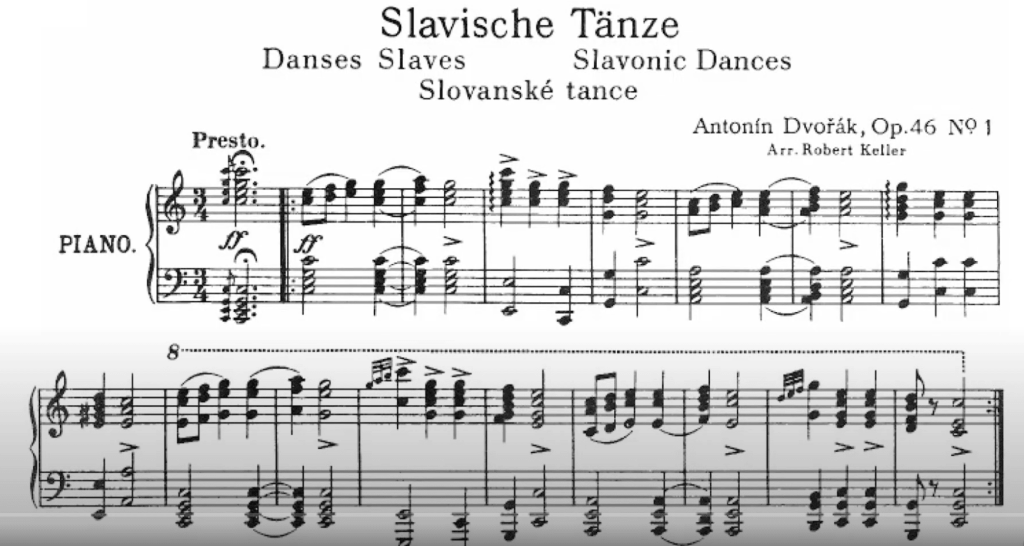

The big thrill in this edition were Robert Keller’s two handed arrangements of the first four Slavonic Dances that Dvořák originally composed for piano four-hands, and better known when we encounter them in Dvořák’s own arrangements for orchestra.

The orchestral versions are full of intricate voices and vivid rhythms: because they’re dances, right?

Now here’s the four-handed piano version, the original that is the first in the eight dances from Dvořák’s Op 46.

The dynamics on piano are so deliciously subtle, they’re a fabulous complement to the orchestral versions. I submit that they’re truly the originals, even if the version most people know and have encountered in concerts or on radio is the version for orchestra. This is true of many of the great compositions we hear from orchestras, that the composer only orchestrated them later.

I stumbled by accident upon the two-handed versions in this Dover collection: but only the first four of the Op 46. Robert Keller is my hero, the man who reduced these towering creations into something for one person. Sometimes the two hands are struggling to fit all the notes onto the page, under the hand.

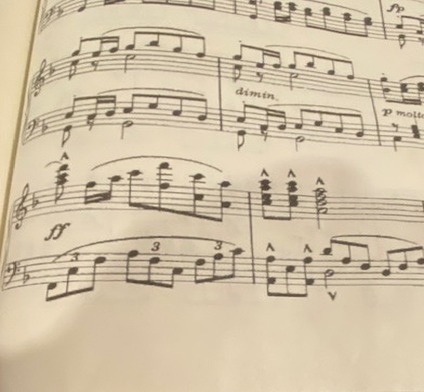

I have been playing this piece for years now, trying to get every note, trying to articulate every voice, trying to properly shade the dynamics. It’s tempting to go really fast: which is a sure way to mess up, if the adrenaline of the furiant gets the better of you. One ends up like Icarus, crashing and burning because one was too ambitious.

The “furiant” is a “rapid and fiery Bohemian dance in alternating 2/4 and 3/4 time“. We see that in the ambiguities Dvořák built into the piece, right on the first line, where one can see phrases that accent as though the count were in 2, while the bars are in 3.

I found another collection of music that includes not just the eight Op 46 Slavonic Dances, but also the later set of eight more, opus 72, all in the two-handed reductions by Robert Keller. That was my big thrill during the pandemic and since. I wish I could promote the book, but as I peruse the Dover website, I couldn’t find the title. Perhaps it’s no longer available. If you see it, I suggest you grab it.

So for example, picture this exquisite four-handed piece, the eighth of the Op 46, which is one of my favourites. Imagine that of all people Jan Lisiecki & James Ehnes play it..! Here they are at a Toronto Symphony concert, with the TSO’s music director of the time (it was recorded in 2018): Peter Oundjian as page-turner.

Notice how delicate the soft melody sounds when Jan picks it up in the middle of the piece. In Keller’s two-handed version it’s not nearly so simple, of course, as the reduction attempts to get all those notes usually played by two people –into an arrangement (i almost said “derangement” which might feel closer to the truth, at times) as played by the soloist.

Now this performance is gentler and more sedate than what one is tempted to do, in surrendering to the passions of the furiant, again with occasional ambiguities between phrasing in 2 or 3. I want to play it at least as fast as James and Jan, indeed, my touchstone for this is the orchestral version i saw done by Zubin Mehta in his last visit to Toronto leading the Israel Philharmonic in 2017. Here he is, conducting a different ensemble in the same piece.

The energies of an orchestra changing tempo furious with the furiant from slow to break-neck fast, are possible when you’re a soloist. That is the magic and madness of playing it solo. Indeed, when a pianist is emulating and imitating a full orchestra one may imagine in one’s fantasy that the piano is an orchestra.

So for the Op 46, there are eight different dances, and only #1 and #8 is a furiant. Here is a list of the dance types of Op 46.

No. 1 – Presto, C major (furiant)

No. 2 – Allegretto grazioso, E minor (dumka)

No. 3 – Allegretto scherzando, D major (sousedská)

No. 4 – Tempo di menuetto, F major (sousedská)

No. 5 – Allegro vivace, A major (skočná)

No. 6 – Poco allegro, A flat major (polka)

No. 7 – Allegro assai, C minor (skočná)

No. 8 – Presto, G minor (furiant)

I retrieved that from the Dvořák website, where I also found lots of fascinating information and images. The numbering on this site corresponds to a different ordering than what I have in my book of the Keller arrangements/reductions. I have adjusted the list to reflect the Keller ordering and the keys as they appear in my book.

I already defined a furiant as a “rapid and fiery Bohemian dance in alternating 2/4 and 3/4 time“, as you find in #1 and #8.

The dumka, as you find in #2 is “a type of instrumental music involving sudden changes from melancholy to exuberance“. That’s a perfect description of the second Op 46 Dance, which starts slowly in a minor key then bursts into a fast melody in major. It’s a split personality of a dance, going from one extreme to the other.

At the piano a soloist may be tempted to make even more extreme and abrupt alterations of pace & mood. I know I’ve tried and I cannot deny that it’s daunting because when one surrenders to the impulse one may suddenly discover that one can’t play all the notes accurately. Argh…

The sousedská as in #3 and #4 is a slow Bohemian dance in three quarter time. It has a calm, swaying character and it is usually danced in a pair. I found that parts of #3 when played at the piano, functioned as extreme ear-worms. When I speak of something as an ear-worm I see that as a compliment to the composer, that they made something that becomes an obsession, refusing to leave my head. #3 is delightful.

Then there’s #4, which is something else. I found that this piece haunted my memory (another sort of ear-worm I suppose?) for years before I found the piano piece, because the melody moves me so much. I remember the first times playing through this piece it made me cry: which can be really awkward when you’re trying to read the page. I say this giggling at the memory but still, fully captive of this piece.

Its first utterance is gentle and builds to a fortissimo climax in the 45th bar.

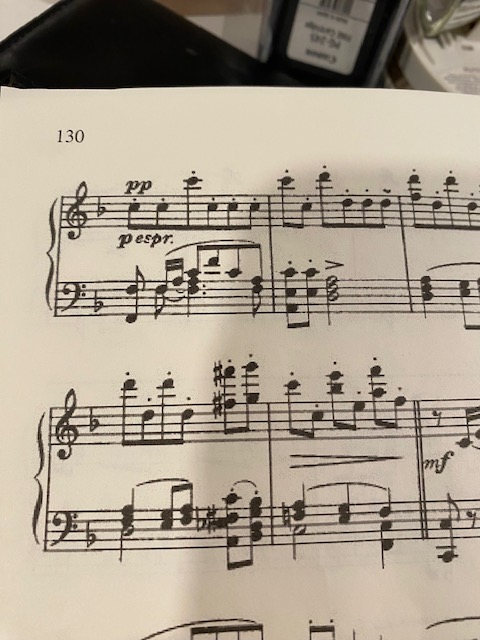

The place that always gets to me is passage where Dvořák brings back the melody. He surprises us by putting it in a tenor register, meaning in the left hand. It sounds so faraway and forlorn it totally messes me up even writing about it.

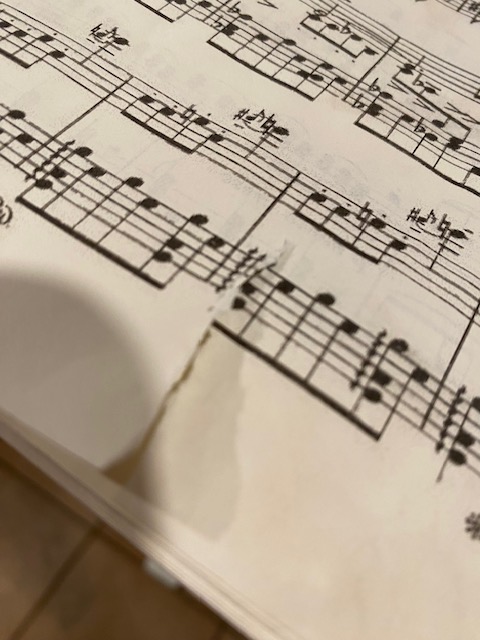

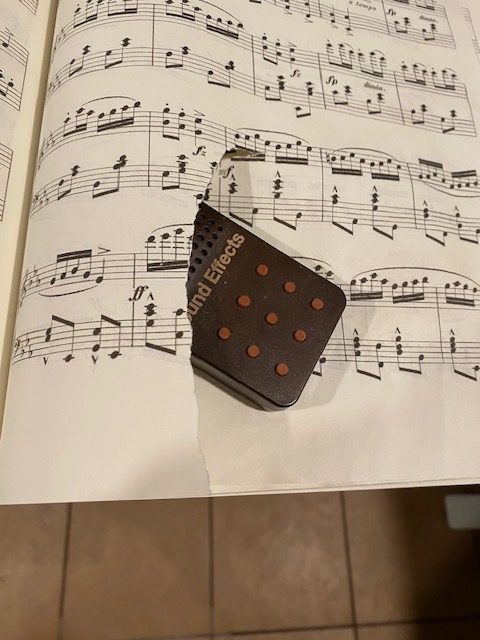

Notice that the left hand has to articulate the melody while the RH is pp, super soft and not stealing the focus. Of course that’s much easier if you’re part of a duo or in an orchestra. In the solo version it’s extra tough AND coming right after a brutally awkward page turn. How brutal? here’s a picture of the torn page, victim of my attempts to get to that soft recapitulation of the main theme.

Two hands play the piano and then somehow there’s a hand turning the page as well. Or tearing it.

For #6 it’s a polka, a dance that originated in Bohemia in 2/4 time. I find this the most soothing of the eight op 46 dances, even though at times it takes off in a huge hurry. Keller does a superb job of making sure everything is right under the hand even when we’re playing something super fast and loud, as we do at the bottom of the first page. Where #2 is really hard to play anywhere near up to speed, this one seems to naturally work without any struggles.

Or maybe the simplicity is a reflection of Dvořák’s genius, the simplicity of the piece before Keller arranged it for two hands.

The Skočná as in #5 and #7 is a rapid Slavic folk-dance, normally in 2/4 metre. I am again guilty of madly tearing a page. It happened when i was trying to play #7, the piece I have known the longest. I first encountered it in the film Allegro non troppo as an animated cartoon by Bruno Bozzetto, that I used to watch with my daughter Zoe when she was quite young.

No wonder we christened / retitled it as “Bunch of bums”.

Dvořák via Keller’s arrangement had me madly trying to play the piece up to speed even as I sight-read it for the first time. Folly.

The piece daunts me as I obviously can’t manage all those notes up to speed, AND the page turn.

There is another set of eight Slavonic Dances op 72, although I confess they don’t move me nearly so much as the first set of 8. #1 and #2 are the two I like and know best, the remainder are perhaps best understood as compositions to be learned and played in another Year of Czech Music. The next one is coming in 2034, by which time hopefully I will have mastered the other set of 8 slavonic dances.

I said there are other Czech composers to mention. Let me speak of two, one who likely will be a total surprise.

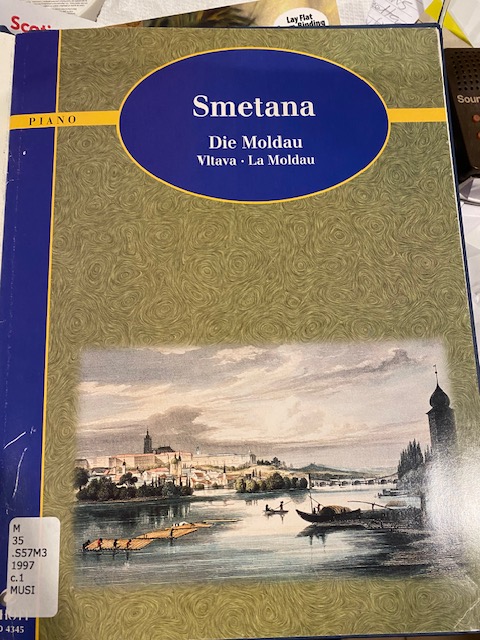

Bedřich Smetana. wrote Má vlast or “my fatherland” a suite of six symphonic poems. I saw a four-handed version of the complete suite in the library, but never expected to find any of it reduced to piano solo. But by a fluke there I was in the Edward Johnson Music Library, and I found the best-known of the six, namely The Moldau, concerning the river. The transcription was there among other reductions of big orchestral pieces (such as Night on Bald Mountain). Schott offer this transcription by Lothar Lechner, a challenging arrangement that is again, full of temptation to surrender to the passions of the piece rather than the prudent management of the fingers.

I love this piece. I sang the melody for my mom a few days ago, as it encouraged her to recall some old tunes. She’s still with us at the age of 103. I was intrigued to read in the introductory essay to the Schott edition that Smetana was living in Sweden, under Liszt’s influence. Maybe his desire to write tone poems is perhaps due to the presence of Liszt. But I’m also intrigued by his exposure to Swedish culture. The familiar melody is Smetana’s take on the Swedish folk tune “Ack Värmeland, du sköna”.

Smetana uses this tune among several in his tone-poem. It first shows up in the pickup to bar #40, and will return after several episodes take us elsewhere on the “river”.

My one quibble is that the melody we know best is Swedish, not Czech. Perhaps we can forgive Smetana, considering that in our journey down the “river” of the piece we also encounter a rustic wedding complete with a polka tune.

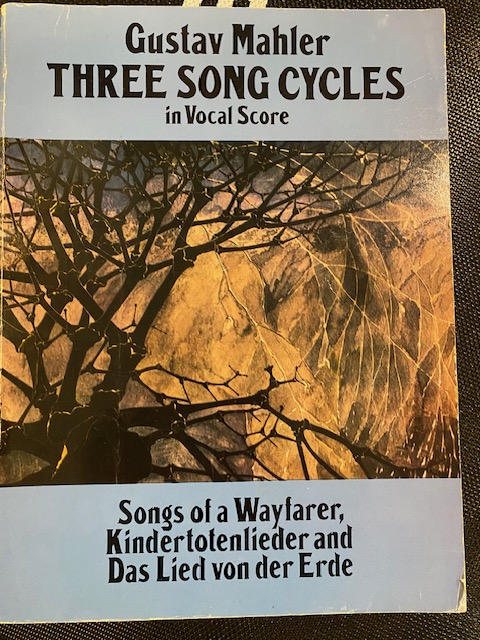

And so the other composer I want to put forward as part of my year of Czech music at the piano–coming from a Hungarian living in Toronto after all–will surely be unexpected. Gustav Mahler was born in Bohemia. I have two books to mention as part of my year of Czech Music.

The first is another marvel from Dover, although I can already anticipate the resistance to the idea of thinking of this as Czech. Perhaps that’s anti-semitism, perhaps it’s simply accurate, given that Mahler himself didn’t identify himself as Czech.

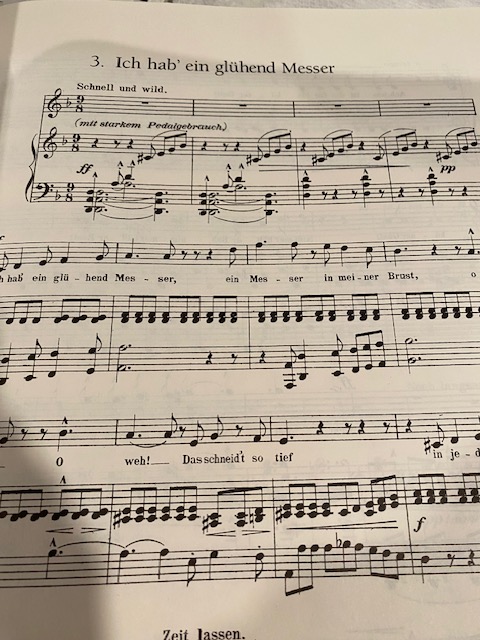

But as I look at the 3rd Song of a Wayfarer, I see something I noticed a moment ago when looking at Dvořák. Remember the “furiant”, identified as a “rapid and fiery Bohemian dance in alternating 2/4 and 3/4 time“? The first line of “ich hab’ ein gluhend Messer” also goes back and forth between duple and triple time, very much as we saw in the first and 8th slavonic dances.

I won’t comment on where any of the other melodies might have come from, only that if we’ll allow Smetana to employ a Swedish folk-tune for his tone-poem surely Mahler can be given some leeway.

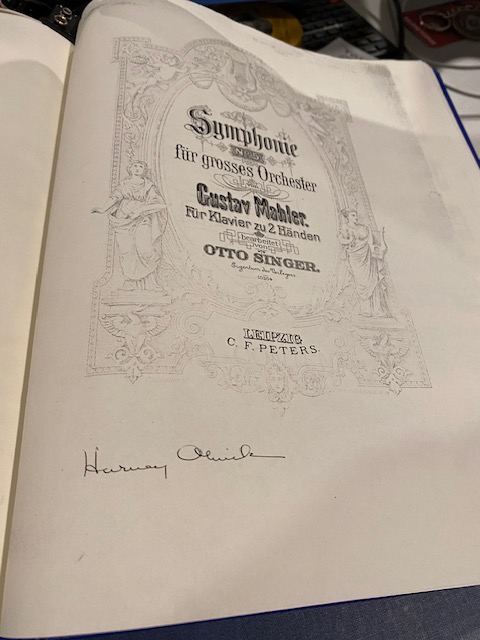

My other Mahler is a transcription of the 5th Symphony that I found in the same fortuitous windfall I mentioned above when I saw the Moldau arrangement. Library shelves can be amazing that way!

This arrangement is by Otto Singer, or as it says on the title page “bearbeitet”. Does that mean transcribed or edited? I’m not sure.

I share that picture because it has the signature of Harvey Olnick, a University of Toronto professor who gave the score to the library. I remember him fondly for his deep voice and generous manner.

I found it stunning to read (when I google him) that

“He exerted great influence at the University of Toronto Faculty of Music; it was largely through his efforts that its music library became the finest in Canada, and he also helped to organize its Electronic Music Studio and plan the Edward Johnson Building.”

Yes. This score for example was his direct contribution.

While I’m playing a reduction of this symphony it’s an astonishing experience to have the whole thing in front of me. At times I think there must be Bohemian folk melodies in this symphony: although I’m illiterate really as far as Czech or Bohemian folk tunes, so I can only speculate. Where does that brash melody come from that opens the 3rd mvmt? Sure let’s give Mahler credit but also, we should consider the possibility that it’s an adaptation of something he heard. Ditto for the melodies in all his symphonies and songs.

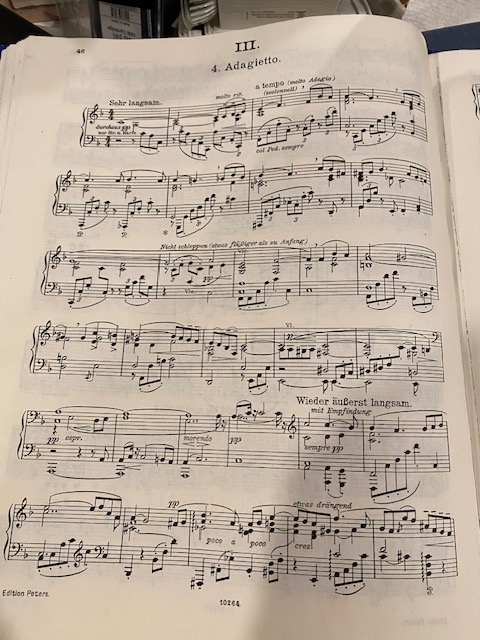

A couple of weeks ago I waded into an online discussion about the Adagietto, aided by the perspective I discovered via this reduction. Oh sure, I can’t claim authority. But as “experts” offer opinions based on their experience as listeners to the symphony, I was able to speak as an interpreter, which is insane when you think about it. I’m no conductor. But I can play the whole 80 minute symphony on the piano, which gives me some perspective as to the role of this gentle 4th mvmt in context with the 5 mvmt whole.

I only bring Mahler up in this discussion of the Year of Czech Music, because I’ve been playing this reduction obsessively, even if I will never get through it up to speed without making mistakes.

I’m especially grateful to the Edward Johnson Building Music Library, who helped me discover so many wonderful scores.