I have just roared through Ardra Shephard’s memoir, a book that I loved from start to finish, wishing it wouldn’t end. I did not expect such a fun book.

If I call Ardra a multiple sclerosis activist it could make your eyes glaze over: but pay attention or you’ll miss the point.

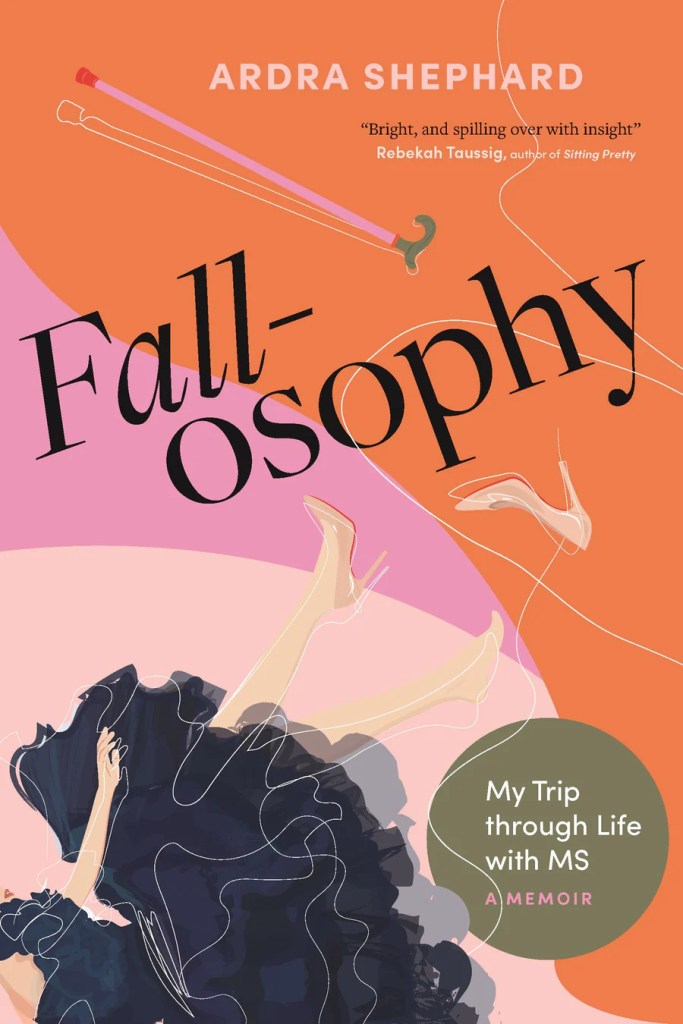

The title Fall-osophy: My Trip through Life with MS is a tiny clue.

And then there’s the cover, the cartoony image showing someone flying ass over tea-kettle, a shoe coming off and a cane launched into the sky. This is a memoir of someone who knows how to live regardless of what life has thrown at her.

In Fall-osophy: My Trip through Life with MS you can’t help noticing that we’re in a realm of puns and jests, the perspective of someone sharing their trips and fall-osophy. Shakespeare would approve, the multiple meanings not so much suggesting comedy as the instability of meaning, the fluidity of a life that is perpetually unstable: as it must be when you discover you have relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis, or RRMS.

To say it’s funny is simplistic. Yes you have to find a way to laugh at the craziness you face with MS.

I’m in awe of Ardra for the fluidity of her prose, making the narrative about her journey feel universal, so relatable that it’s irresistible, overwhelmed to encounter so much wit so much brilliance. I am a bit starstruck to be honest. I fell for Fall-osophy, tripped up by its language and kick-ass attitude. I was seduced because instead of something serious and heavy and telling me what to think, I found myself giggling at every page, sometimes every paragraph, wishing I’d been invited to the party or at least asked to play the piano while she sang. Ardra is in your face challenging assumptions as though she’s somewhere between AOC and a stand-up comic, when she’s not telling us about not being able to stand up. I thought of the mouthy comedy of a Joan Rivers or a Chelsea Handler: confronting MS, confronting our dumb-ass assumptions, confronting thoughtless people. I was uplifted by this positive energy that inspired me even as I was also moved. Yes a few times I was surprised by tears precisely because it was never where you expect.

Great writing.

At several points I stopped reading to make notes, wanting to capture Ardra’s wisdom. For example at one point she articulated something Erika and I have struggled with for decades.

Ardra wrote

“On some level, I already have a sense that one of the burdens of being sick forever is to let others know I’m okay.“

First off: yes chronic illness means “sick forever”: a funny turn of phrase, but that’s why it’s powerful.

And holy shit this impacts relationships, especially loving intimate relationships. This might be the most romantic book I have ever read because of how truthful it dares to be. I’m almost ashamed to admit it, because my version of reality was so full of denial and avoidance of pain. Ardra is braver than I.

As a man whose diagnosis for his own tiny chronic condition (minor compared to what Ardra faces, please note) took more than a decade, I had lived a lie, pretending to be normal and okay, sometimes in remission sometimes in pain, faking it because that was my only option. Erika helped me understand that one of the indirect results of my duplicity –pretending to be okay, living in denial of my own pain–was that I was always in denial, sometimes furiously so, making me hard to live with. Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt, it’s a pain management strategy. If I pretend I’m okay maybe I will be okay: or that was the plan, especially in the decade plus before I knew what was wrong with me. I could get very touchy about being asked if I was okay, as someone who was only pretending to be okay. And yes I know this sounds crazy. The thing is, reading about Ardra’s experience, her brash response to her diagnosis, has been like therapy for me, putting me in touch with the disconnect between expectation and reality.

But I need to point out that this is far beyond MS, because it’s universal as we all get older, at some point acquiring limps and bunions, hunching over, having trouble hearing or seeing or moving, in the disability drag show of simulating competence rather than admitting our need for help. We are all tasked with this question of whether we ask for help, whether we will let others know we are okay. But of course Ardra got the diagnosis at 23, meaning that she began to be aware of the consequences and implications of aging way earlier than most of us.

Another passage that hit home was when she suggested that the diagnosis was in some way her own fault. Ardra wrote

A few weeks later I will think back to that drunken night and consider that my attempted conversation with the underworld and the shady deals I tried to strike with the Prince of Darkness somehow led to my diagnosis. Random shit doesn’t just happen. Bad things happen to bitchy people, and it couldn’t just be terrible luck that I’d gotten MS. There had to have been a reason, and for a few years, I will believe the reason is me.

So in addition to bearing the burden of the diagnosis, there was blame.

We watch a progression in the romantic story she tells, wondering if the bf The Bartender aka TB will still be in the picture later in Ardra’s story.

For the rest of the trip, The Bartender never takes his eyes off of me. He seems to know when I want to move and is ready with an arm to steady me. I’m not completely incapacitated. We still lounge by the pool, play cards and go to the shows. We’re still having sex. But it’s not the same. My whole body feels foreign to me. Like I’ve been Freaky Friday’d and I’m existing in someone else’s skin, waiting for lightning to strike and put me back in my own anatomy.

I’m reminded of the dark humour of Trainwreck, trying to hear how this might sound if it were Amy Schumer delivering her verdict on Bill Hader.

The Bartender has taken good care of me, but back in Canada, he drops me off at my parents’ place looking visibly relieved. My mom invites him to come in and have a drink, but he declines. Like an under-qualified babysitter handing back a kid they had no idea was an uncontrolled pyromaniac, he can’t get away fast enough. I can’t blame him. He signed up for a sexy beach vacay, not an unpaid internship as a personal care worker. I didn’t exactly nail fun, cool and low maintenance, but I have bigger things to worry about.

This is much more than a story about MS. We see real-life implications for relating, for living, for loving. And it’s so authentic, so blunt I couldn’t stop reading.

The conflict between empowerment and the underlying powerlessness of MS lurks in the depths of this story.

With the exception of Dr. Poker Face, who uncharacteristically has an ominous reaction when I skip into his office declaring myself basically cured, everyone compliments me for how I’m fighting this disease and winning. My MS is stable and I’m taking all the credit. I have smugly solved MS.

Of course, the flip side of giving yourself props for doing well with this disease, for believing you control the outcome, is what happens when you have another attack. If fighting is all it takes to beat MS, who’s the loser when there’s another relapse?

Irony is a big part of Ardra’s toolkit, as she regularly tosses dark questions at the reader, working through stages of accepting the diagnosis. I wonder if there’s something equivalent or analogical to the Kubler-Ross stages of accepting death at work? her vulnerability is astonishing as she lays herself bare before the reader. For example…

I think back to an event I attended when I was first diagnosed—a “Welcome to MS” information night when Mac’s top neuro talked to patients about treatments and research. When he said that in all of his years of treating MS the patients who did the best were the ones who accepted their diagnosis, I was outraged. I thought he was a quack. What kind of doctor tells you to kick back and accept it? My intention is to fight this disease with everything I’ve got, and to me that means being on high alert.

Of course, the cost of my vigilance is steep and unsustainable. Every day, I wake up worrying about my next relapse, but crying and freaking out don’t seem to be staving off attacks. I don’t know how to not be scared of what is unquestionably scary. Although most of my moods are future-based daymares, I can’t deny that I miss the old me. I miss all of the mes I could have been if MS hadn’t entered the picture. Maybe I am depressed. I book a follow-up appointment and get on the bus to go home.

And Ardra’s tone and outlook change several times on our way through the memoir.

Yet fun is still possible.

A day of pampering isn’t what it used to be. No sufficient word exists to describe the pain of dysesthesia. My feet are medically cold. My toes barely warm up in the spa’s tub of what I presume is hot water. My toenails are the colour of frostbite and the aesthetician tries to scrub off what she imagines are the remnants of blue polish (and not a sneak peek at my future corpse feet). Pedicures trigger spasticity, which causes my legs to seize, and/or clonus, an abnormal reflex that makes my feet bounce uncontrollably. I tend to tip extra if it even seems like I might kick my pedicurist in the face.

I hope I don’t seem to be a psycho that I find Ardra’s writing funny, but her self-deprecatory confessional writing slays me totally. She’s not letting MS stop her, and it’s beyond admirable. At moments like this I return to the title and the image on the cover of the memoir.

The Manhattans were my most recent bad decision, but my first mistake was my choice of underwear. I lost my balance trying to pull down my skin-tight slip and stumbled backwards over (and kind of into?) the waist-high garbage can. And that’s how I ended up huffing bleach on the floor. All because I am incapable of putting comfort and practicality ahead of style. Well, that and also alcohol. MS was a factor, but I think we can all agree I did this to myself.

I should know better.

I do know better.

This is my fault.

While Manhattans aren’t what I drink I admire the dryness of the descriptions if not the drink (which isn’t dry).

The deeper we get into the book the darker the prose. To each their own, but I love the way she handles the darkness.

Statistically, MS shaves roughly eight years off of life expectancy, which sounds a lot to me like MS is, in fact, coming for you, albeit eventually. … But eight years is the lifespan of the average Saint Bernard, and I for one am not comforted by the thought of MS shortening my life by one whole dog.

The story becomes more serious, as for instance in contemplating a medically assisted end of life scenario.

It’s upsetting to realize that while I continue to wait for a spot to open up in rehab, I could be approved for MAID (Medical Assistance in Dying) in just ninety days. In addition to complaints of insufficient, under-resourced health care, a staggering number of disabled people point out the critical lack of adequate accessible housing that is driving them to seek out MAID. With so many sick people struggling to simply exist on a disability income that keeps them in poverty, it’s hard to believe that policy-makers are ultimately concerned with “dignity.” When death is the alternative to a properly funded health-care system, it starts to feel kinda eugenics-y.

There’s so much more to Ardra’s life than this book as you discover when you read the jacket cover, and she’s living that life with authenticity.

Tripping on air is Ardra’s blog.

There is also a podcast.

The book is the outcome of her growth as a media creator and writer. I’m in awe of her writing style and her attitude to life. If I’ve persuaded you to consider buying the book, here’s the link to Douglas & McIntyre’s website, where you can have a look.

Thanks so much for this beautiful review, and for drawing our attention to this book; it is next up on my reading list!

I’m lucky when something extraordinary comes to my attention. Pinch me!

I just finished reading Fallosophy and wanted to thank you again for this beautiful review and for introducing me to this remarkable book. It truly is everything you describe—and so much more. I am delighted that an audiobook version is coming out on July 15, which will help bring this gem to an even wider audience. This is an enlightening and deeply moving book. Ardra Shephard is an amazing writer … what a gift with words, what a superb wit, what a talent for telling it like it is. I sincerely hope that a sequel is in the works!

I’m almost finished and am awed by how this book is impacting me in so many ways… amazing !

No kidding. This isn’t just a book with a narrow focus, not just a book about MS. While Erika didn’t read it (yet) I was discussing it with her the whole time. Oh and of course I will re-read it. Full disclosure: reviews are a great excuse to dive back into something you love.

Generally the publisher does NOT comment on reviews…but…we love a personal and empathetic commentary/review that so completely gets at what the heart of a book is about. Thank you for taking the time to read and distill your response to Fallosophy.

Thanks for the kind words. I felt a bit like that ice-storm, that left pieces of trees broken all over lawns in Southern ontario. I was chop chop chopping because I had so much more to say. I was first & foremost impressed with Ardra’s economical writing style, and was probably improved from being exposed to her prose (it rhymes?).

Pingback: Asking Ardra Shephard about her Fallosophy | barczablog