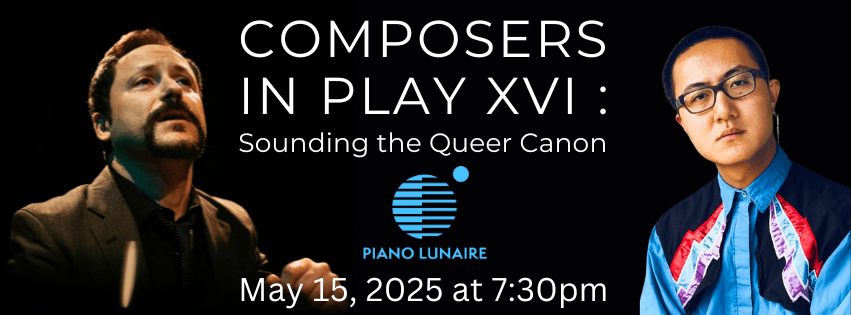

Thursday night at 7:30 pm May 15th, at the Arts and Letters Club, Piano Lunaire will present COMPOSERS IN PLAY XVI, a concert subtitled “Sounding the Queer Canon”.

I asked Piano Lunaire founder Adam Sherkin a few questions about the program and its objectives.

*******

Barczablog: Who organized / curated this program?

Adam Sherkin: This program grew out of discussions between myself and baritone Nathaniel Sullivan, at least initially.

Nathaniel is one of those unique artists who brings care, intent and expertise to everything he touches. I was struck by his willingness to curate a program in collaboration that could be dynamic, compelling and enigmatic, all at the same time.

We especially set out to find a musical space for celebrating queer composers of our time and not-too-distant past that didn’t have to answer EVERY question nor provide a definitive “take” on the meaning of, or the content within, such a queer musical canon. From the outset, Nathaniel and I were comfortable fashioning this recital from a neutral, investigative zone of origin, armed with the conviction that this could turn into a long-term project, spanning multiple song recital programmes, engaging several new composers and years of collaboration.

It was Nathaniel who recommended mezzo-soprano Claire McCahan come on board to plan for COMPOSERS IN PLAY XVI, (originally slated to be presented in NYC).

In order to do justice to Michael Genese’s, A Boy with Baleen for Teeth for mezzo-soprano and baritone, a voice like Claire’s was an important piece of this project. Claire immediately took to task with enthusiasm and spirit: she has now expressly contributed to the crafting of the recital that we present on May 15th in Toronto.

Her particular recommendations include “How do I find you?” by Caroline Shaw, and the touching, intimate setting from Annika Socolofsky, “loves don’t /go.”

Claire is a good friend and colleague of Socolofsky.

BB: what is your understanding of “queer” and how should we understand it?

Adam Sherkin: The reclamation of the term “queer” that has evolved since the 1980’s by activists and members of the community proves inclusive, hopeful and empowering. As older generations will recall the pejorative context of the label “queer,” the LGBTQ+ community of today embraces the terminology and moves forward in vigilant efforts to include those historically marginalized. This has become part of the and fight for equality and human rights, not just in North America but throughout the globe’s countries that continue to criminalize queerness. As to how an audience at a contemporary classical song recital might understand the meaning of “queer,” each person will bring their own context (even one of unfamiliarity) as they take in new sounds. Culturally significant queer work is what we are seeking to share at this performance. We wish to present high quality music from the western classical tradition that is undeniably queer in its origin, its content, and its mode of being/mode of sounding. This is the spark — the initialization — of a larger discussion and experience of queer culture and, specifically, queer classical music as a sampling from the last thirty years in North America.

BB: The program title suggests questions. What is your understanding of the”𝐐𝐮𝐞𝐞𝐫 𝐂𝐚𝐧𝐨𝐧”. Please unpack that for us.

Adam Sherkin: This is such an interesting question, and strikes at the very heart of what we are attempting to share and prompt here. The honest truth is: we don’t (yet) have a full understanding of the Queer Canon, at least not in classical music. The queer canon of, say, literature or visual art is more readily identifiable. The practice of music, for all sorts of reasons, remains aloof, abstract and somehow less quantifiable. Nevertheless, that should not deter one from exploring such possibilities, such riches. Let us begin with simple queries such as: what musical content makes a work queer? Extra musical content is more obvious to profile but how might queer text, for example, interact with a queer sense of harmony or line? Of the major five musical parameters (ie. melody, harmony, rhythm, dynamic spectrum and texture/sonority), which of these could be accurately identified as born of or integrated into a queer musical aesthetic? Indeed, what constitutes the queer musical aesthetic?

If we infer that, through performance practice and audience feedback, academic research and sonic dissemination, that a canon of music can develop, then where and what is the queer musical canon? Arguably, composers such as Tchaikovsky or Schubert would never have identified in such a way. More than an anachronistic rub, their origin point for their creativity could not benefit from flourishing in a society that openly celebrated, let alone, accepted queerness on a wider stage. Benjamin Britten was out in private but existed, yet again in a different time. However, composers such as he could be singled in tracing a contemporary queer canon pursuing investigations into the nature of Britten’s craft and musical voice from a queer vantage point.

A final consideration here (a mere graze of the surface on this vast ocean-topic), is trauma and suffering in a given community or self-identifying group. While the ravages of HIV/AIDS continue to affect parts of the world here in the 21st century, in the west it was the queer community in the 1980s that first confronted what was then a fatal disease and had to find a way to survive it and make sense of such cataclysm. These experiences – in a shared context – might also affect the canonic nature of art made by artists who lived or died in such punishing times.

BB: tell us more about the works on the program.

Adam Sherkin: Two of the important centrepieces to this programme are cycles from David Del Tredici and Chris DeBlasio – both of whom, incidentally – are no longer with us. Del Tredici passed away less than two years ago in Fall of 2023 and DeBlasio left us far too young, aged 34 in 1990, dying from AIDS-related causes. Both works explicitly address American queer experience and in particular, historical incidents that were germane to a queer identity. For Del Tredici in the third song of his Baritone Cycle, “Matthew Shepard,” his own shock and experience of the murderous hate crime perpetrated against Matthew Shepard in 1998 along with the words of James Manrique moved him to create this inspired and significant piece (dirge-like in its story-telling and setting; there are musical references to Chopin’s Funeral March.) Del Tredici wrote, ‘Matthew Shepard’ by Jaime Manrique touched me. The brutal homophobic death of this innocent resonated with my own loss through AIDS of a young lover, Paul. To surround with music that moment when the soul leaves the body, that transformation of pain into bliss, was my inspiration and challenge.”

The song opens:

IN THE FINAL MOMENTS

when the station wagon

pulled away, I shivered

and was thankful to feel something

Blood glued my eyes

I thought: the last thing

I want to remember

is not the look of hatred

in their eyes.

Excerpt from “Matthew Shepard”

From “Blood and Tears, Poems for Matthew Shepard”

Copyright by Jaime Manrique

Published by Painted Leaf Press

For DeBlasio, the exquisite poetry by Perry Brass led him to this powerful yet intimate set, All the Way Through Evening (Five nocturnes for Baritone and Piano) about an all-too-common experience of losing young healthy men to HIV/AIDS and the unfair and seemingly indiscriminate nature of that fatal illness. In DeBlasio’s setting, we perceive the loss of a friend or lover, companion or family member with intimacy and the weight of personal tragedy. And yet such experience of death of HIV/AIDS in the queer community of the late 1980’s and 1990’s were so widespread and similar in its unjustness, that this cycle of Deblasio’s transcends the individual experience and speaks to an entire community in their grief, as a record of what happened during that terrible time period.

Acclaimed American poetry Perry Brass has had an impressive career and continues to write today. His work has been part of the AIDS Quilt Songbook and the five poems DeBlasio set from Brass have been an integral part to the poignancy of All the Way Through Evening. From the fifth (and final) song of the cycle:

Walt Whitman in 1989

by Perry Brass

Walt Whitman has come down

today to the hospital room;

he rocks back and forth in the crisis;

he says it’s good we haven’t lost

our closeness, and cries

as each one is taken

He has writen many lines

about these years: the disfigurement

of young men and the wars

of hard tongues and closed minds.

The body in pain will bear such nobility,

but words have the edge

of poison when spoken bitterly.

Now he takes a dying man

in his arms and tells him

how deeply flows the River

that takes the old man and his friends

this evening. It is the River

of dusk and lamentation.

“Flow.” Walt says. “dear River,

I will carry this young man

to your bank. I’ll put him myself

on one of your strong, flat boats,

and we’ll sail together all the way

through evening.”

The third significant item on this programme, one by a young, living composer is the lucid and stirring setting from Michael Genese, “A Boy with Baleen for Teeth.”

This coming-of-age narrative unfolds over nearly ten minutes making expert use of both voices and piano textures. Genese takes much direction and inspiration from the wondrous text by Rajiv Mohabir:

Mohabir describes the main character as “a falling star into the abyss” as they leave their family in the middle of the poem. The piece concludes with them trembling mid-air, “stars shone through the holes of my body,” almost a beacon of light for those who later struggle with community and identity as they have. The long-lasting damage done to queer people by western colonization’s ever-encroaching philosophies of binary gender, nuclear family structure, and societal respectability has policed and estranged us from communities in this way for centuries. This harm extends at several intersections to the struggles of Indigenous people, Black people, and all who threaten what James Baldwin called the “stupendous delusion” of whiteness in America, queer or not.

BB: Who are the artists?

Adam Sherkin: As he self-proclaims, Nathaniel Sullivan, “is a musician, theatre artist, and writer devoted to holding space for reflection, understanding, and creative projects that champion change.” He is currently based in NYC and in demand both in the northeast and midwest where he grew up. Many highlights to note from his 2024-25 concert season. Check out his website (not to mention personal reading list!) and read his thoughtful and beautifully written blog.

Claire McCahan (note her social media “the wild mezzo”) seems to sing it all! Based in New Hampshire, her singing career continues to thrill and evolve: spanning baroque, recital, opera, and contemporary repertoire. She has a knack for narrative style and story-telling; she also composes and arranges songs herself!

We are thrilled to have Michael Genese able to join us in person. Two of their works will be featured on this programme, including the solo piano piece with electronics, Meditation on Sphere of Influence, presented by Piano Lunaire in February of 2024 in New York. Michael is not just a composer – but a singer and multi-instrumentalist as well. They are also an Artist Ambassador with the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) and continue to pursue important justice work.

BB: Is this the first time the program will be played?

Adam Sherkin: Very much a first outing for this repertoire. Piano Lunaire presented one of these songs in June of 2019 in Toronto: David Del Tredici’s “Matthew Shepard” at a fundraising event for Rainbow Railroad. Otherwise, this is an evening comprised of firsts, including several Canadian premieres. Composer Michael Genese (who has two works being featured on the program) will be heard for the first time by Canadian audiences: a true northern debut! We had hoped to perform this in NYC as well but we are sticking to Toronto only for the moment. With any luck, other presenters might pick it up and offer us further opportunity. There are more ideas where these came from and lots more repertoire from the canon to sound.

BB: Do you see this program as being educational and activist?

Adam Sherkin: This programme is likely educational in nature, insofar as all new work can enlighten, challenge and surprise us; it should edify if we allow it. But there is nothing particularly activist about what we are doing. Simply put, we are story-telling: seeking for more historical context, more weight to music we believe is deserving of repeated listening and of occupying a rightful place in a larger musical canon. Importantly, any performer – LGBTQ or otherwise – might like to take up this music and present it. Reciprocally, any listener, LGBTQ+ identifying or otherwise may find it compelling and worthy to listen to. This explicit framing of queer music is not a new thing. It’s been well considered and exceedingly well presented by various organizations and artists for decades now. Some of these presenters solely offer queer-based music at their events.If the very content of this programme moves the listener enough to take action – to leave the hall and want to know more, understand better and act in the interests of human rights and justice for marginalized members of the queer community, then one could term what we are doing here as activism. But really, any good art or music should compel and inspire, aspiring to change people’s lives for the better.

BB: Tell me how the program might encourage us to “reconsider identities of Queer artists in contemporary classical music”

Adam Sherkin: The encouragement here for reconsideration is perhaps an urging for renewed and unprejudiced listening: try, if you will, to listen afresh to (well, new!) music by composers you might know something about already. Why not perceive them in an immediate context of our world today with as little bias as we can muster as individuals? This is, of course, very challenging for us all, as we all bring our biases – political, musical and otherwise – with us into the concert hall experience. But finding a way to objectify (in the best sense) the work of queer musicians and attempt to discern the value – the currency, if you will – in their art might prove meaningful and even illuminating. This act of reconsideration then could create interest in our next PL program and begin to fulfill the vital role of critical mass/attentive listenership in the contribution to, and the (re)consideration of, a queer musical canon.

BB: Toronto feels like a safer place than NY or LA right now, at least for any possible travellers. Do you expect to welcome anyone from outside Toronto to attend?

Adam Sherkin: One must admit that Toronto is a far safer place than any major American city right now, even the traditionally LGBTQ+ friendly metropolises. This is, of course, due to the current federal government in Washington and its increasingly public battle against queer rights; what they term “gender ideology.” Members of the trans community have already been expressly targeted with an executive order recently upheld by the Supreme Court baring trans people from military service and restricting transgender care for minors.

Towards travellers to Toronto, the queer community remains welcoming and evolved in its acceptance and integration. While we still have much work to do here in Canada, we can offer safety and inclusivity to those folks visiting from other countries. Piano Lunaire has endeavoured to be an increasingly active and contributory member of the Toronto LGBTQI+ network. Indeed, singers Nathaniel Sullivan, Claire McCahan and Michael Genese are each American nationals who relish the opportunity to present their artistry to a Toronto audience.

(This program was originally conceived for Piano Lunaire’s NYC series, especially given the prevalence of New York-based composers on the programme. Due to the unraveling political situation in the US, we have opted to present the recital here in Toronto instead, at least for the time being, as some of the personnel felt unsafe being in the United States under the current administration.)

BB: Lest we get too cocky about Toronto, what should allies remember as far as how to approach attending such a concert.

Adam Sherkin: We all ought to remember how best to be allies for any other membership in our society that does not share the privileges we do. For allies of the LGBTQ+ community, all are welcome and remain important to what we are trying to achieve at PL’s Thursday night show. Generally speaking, it is the hope of nearly all creators that their work be received by a wider, even global, audience and that it might touch the ears and hearts of all human beings. That also holds true for queer creators in music: the stories we have to tell and the musical materials we work with are the food of love for all audiences who might value it and wish to share in its message. Music as an art form can sometimes seem non specific, even abstract. This could offer even a wider margin of acceptance to non LGBTQ+ audiences as the details for the queerness in this art need not be overstated. But such perception and profiling does a disservice to our community here. The explicit queerness of the art must be celebrated, highlighted and cherished, even in its most abstracted iterations. Let’s journey together into this canon and find meaningful notes and words that move us, bringing us together as humane individuals passionate about music, who adore art and love one other.

BB: Do you want to acknowledge any mentors or influences, making this possible?

Adam Sherkin: Our donors and patrons at Piano Lunaire have long supported such curatorial visions and continually encourage us to keep innovating in many realms of new music, including the realm explored here in COMPOSERS IN PLAY XVI.

The Arts & Letters Club, being an historic and long-standing Toronto institution founded by journalist Augustus Bridle as a gathering place for artists, writers, musicians, and performers, today increasingly looks to the future, welcoming younger generations through their doors.

They have been most generous in partnering with us on all programmes, including this one. Piano Lunaire has been happy to support the work of Rainbow Railroad in the past and continues to do so. This Canadian-born, global non-profit organization remains a beacon of inspiration and hope, especially those members of the international LGBTQI+ community being persecuted and punished in their home countries and in urgent need of safe haven.

ChamberQueer in Brooklyn has been a great inspiration to our work on this programme, as has the Queer Poetry Collective, The NYC Gay’s Guys Book Club (under the exception stewardship of Jon Tomlinson), Counterpoint Community Orchestra, The Toronto Gay Men’s Literary and Arts Salon (led by the intrepid David Hallman), The ArQuives (Toronto), The 519, The Center (NYC), NYC LGBT Sites Project and OperaQ here in Toronto. (Be sure to check out their upcoming collaboration with New Music Concerts on June 11th, “Glimmer: a personal and shared exploration of Queerness. )

PROGRAMME:

CAROLINE SHAW – How do I find you? (2018) for mezzo-soprano and piano

DAVID Del TREDICI – Three Baritone Songs (1999): No. 3, “Matthew Sheperd; text by Jaime Manrique

EVE BEGLARIAN – Farther from the Heart (2018) for voice and piano

CHRIS DeBLASIO – All the way through the Evening (1990) for baritone and piano; text by Perry Brass

~ ~ ~

ANNIKA SOKOLOFKSY – loves don’t / go (2016) for mezzo and piano

SHERKIN – CARETAKEROFDREAMS* for baritone and piano; text by Fan Wu

MICHAEL GENESE – MeditatIon for Sphere of influence** (2022) for solo piano/electronics

GENESE – A Boy with Baleen for Teeth** (2023) for mezzo, baritone and piano; text by Rajiv Mohabir

* WORLD PREMIERE; Piano Lunaire commission

** CANADIAN PREMIEREThursday, May 15, 2025 at 7:30pm: The Arts & Letters Club. Doors open at 7:00 PM; performance at 7:30pm. $25 General admission; $30 Seniors and art workers; FREE for students. Cash Bar and refreshments available throughout the performance.