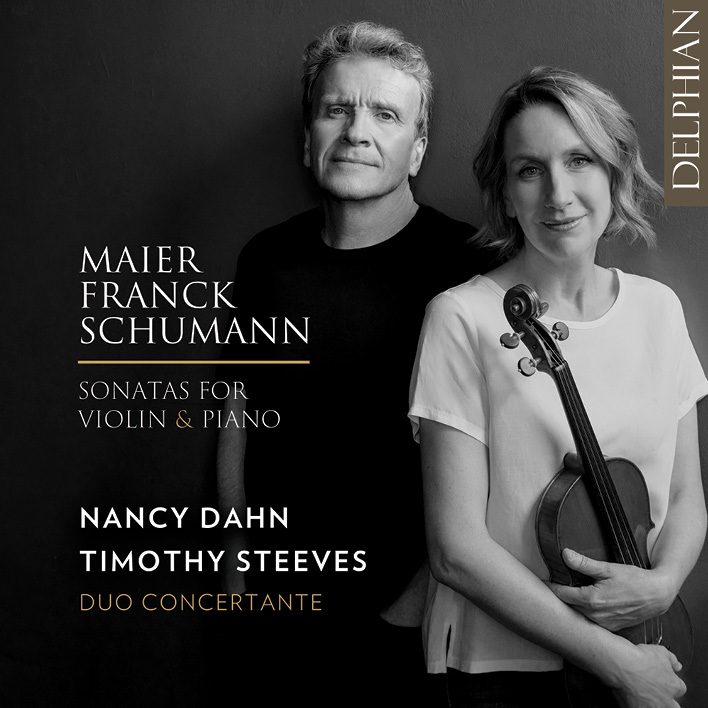

Add Nancy Dahn’s violin to the pianism of Timothy Steeves and you get Duo Concertante. I’m a fan who enjoyed their previous outings playing Beethoven and the edgier pieces on their Ecology of Being recording from 3 years ago.

Their latest creation features three violin sonatas by a trio of composers.

The recording is a reminder of the many ways we understand that word “romantic”. Guillermo Silva-Marin reminded me in his introductions at the Opera Salon of the breadth of that word, now having become so inclusive as to have almost lost its original meanings, that were shaped back in the time of the first of the Duo’s composers.

That would be Robert Schumann (1810-1856) who composed his first violin sonata in an impulsive burst over the span of four days in 1851. I am reminded of one of the attributes we find in some of those early romantics such as Schubert or Chopin, making compositions with the feeling of spontaneity, impromptu, feelings seemingly close to the surface. While there may still be structural elements of the classical period such as sonata form, that becomes the departure point for explorations, enlarged possibilities and pushing the limits of what was understood to be allowed. Romantic music grew louder than classical, the limits of the virtuoso always being revised in pieces that were more difficult to play than the previous generation. Schumann is remembered as a troubled figure, tormented & suicidal, disfiguring his own hand in hopes of increasing his own reach & strength. But while his music can be played with passion one can and must transcend pain in seeking the beauty in his melodies & his unique pianism.

The opening phrase of the violin sonata in A minor leads ambiguously away from its beginning key, as the duo build to a series of climaxes, the violin & piano surging together then pausing on a discord that brings us back to the beginning key. The second movement has an improvisational quality, spontaneous as the moment the next phrase appears, seeming brand new in the dialogue between Nancy & Timothy, delightfully bouncing off one another like a romantic conversation.

The finale is powered by a softly pulsing piano that is answered by the violin, leading to the end of the statement and then flying off into another key, very much like discourse with its resemblance to question and answer, back and forth building to bigger and bigger questions being tossed between them, until a soft lyrical passage in triple time allows a rest from the agitation. And then when we get to the cadence it starts up again with another version of that pulsing piano thing, but softly.

They are so musical together it really feels like a couple who finish sentences for each other, softly doing it in phrases that resemble a single thought shared between two people.

And next among the three composers on this CD, Amanda Maier (1853-1894), a name that’s new to me, a woman composer, herself a violinist among male violinists and composers. I read that she was the first female graduate in music direction from Stockholm’s Royal College of Music.

Maier died even younger than Schumann. Her sonata seems to be a contrast to that of Schumann, not a spontaneous eruption but a deliberate & carefully built work composed over the course of 1874 & ’75, a vessel to contain simple but powerful emotions, each movement’s opening phrase seemingly linked. Her sonata stands tall between two giants, a worthy peer to the famous composers on either side of her on the recording. You can read more about her in a 2009 essay I found titled “Unjustly neglected composers: Amanda Maier.”

Her B minor sonata opens with a simple phrase that becomes a building block for the first movement. The phrase is like a thought upon looking outward, that enlarges its scope, widening with every reiteration of the little idea that started it. Nancy and Timothy are together as usual, the questioning of this movement like eyes glancing left, right, wondering. The second movement’s lyricism is song-like, moving gently in triple time like a slow dance, the minor third of B-D that seats us in B minor for the first movement takes us this time into a gentle song when we’re in the key of G major, using the B-D not as tonic to mediant but mediant to dominant. The third movement to conclude has us back in B minor, including a minor third to declare the theme and our return to the opening key.

When we come to the third romantic exponent, Cesar Franck (1822-1890), we are in the presence of a sophisticated exploration of the relationship between violin & piano, their chromatic harmonies taking us further, deeper, in a four movement work.

Franck’s great work was composed for the wedding of virtuoso Eugène Ysaÿe in December 1886. The manuscript was given to Ysaÿe on the morning of the wedding by a mutual friend, Charles Bordes. Eugène practiced the work with pianist Marie-Léontine Bordes-Pène, Bordes’ sister-in-law. They premiered the work for the wedding guests, giving the public debut months later. The sonata has been understood in the most romantic terms ever since. For example Franck’s sonata was one of the last works Amanda Meier performed in concert with her husband.

The first movement is a fantasy, a gently tentative enquiry expanding gradually into broader and bigger prospects as though opening a window or a door, looking out upon and then visiting a landscape. There’s a back and forth between violin and piano, not so much call and response as statement and echo, the replies sometimes darker. The piano for that first movement is like a foundation holding up the upward reaching violin, sometimes becoming energized.

The second movement is agitated, a powerful allegro that involves us in some ambiguities harmonically, and slowing down for passages resembling recitative, as though pondering deep questions. The piano is now driving us onward in challenging quick passages, no longer in the background. We go back and forth between darker harmonies and gentler melodies, the work building to a radiant climax, the two instruments matched finally.

For the third we are again pulling back, a series of cadenza- impromptu moments to suggest contemplation. We are hearing a simpler texture from both instruments, the piano and violin confronting the world in the gentlest terms, the questions presented tenderly, with a kind of vulnerability, even affection between the two voices.

And then we come to the final movement, surely one of the move beautiful creations for violin & piano, one voice after another answering, surmounting, complementing. While I have been listening to this piece since I was young, it sounds especially beautiful in its setting here on the recording by Duo Concertante, set up by the other two earlier sonatas. I find I play through the CD and then start over, that it’s a natural organic journey.

I have been listening to their performances on CD for literally weeks, as I thought about the best way to write, hoping to capture my enjoyment. When I started listening the perception was different, orienting myself movement by movement, but as the CD became more familiar it turned into one continuous meditation, each composer adding their own perspective, their own unique answers to the questions we would understand as fundamental to romanticism.