Tis the season. At a time of year when it can be so cold that one prefers to dream of next year (even if it’s been unseasonably warm to begin 2016), the major classical music organizations make their big announcements.

- A couple of weeks ago it was #COC1617 as the Canadian Opera Company launched their new season & drive for subscriptions

- Earlier today Opera Atelier announced their new season

- Next week it will be the Toronto Symphony’s turn

- And tonight it was Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra.

Tafelmusik’s event “Season Launch 16/17 enacts everything in miniature that this orchestra stands for. The event was for a small circle of key donors, including a lovely series of performances, led by Mira Glodeanu as director & violin soloist. At this point I’d like to quote the press release which said the following:

“In June 2014 Jeanne Lamon stepped down as Music Director, and is continuing as Tafelmusik’s Chief Artistic Advisor until her successor is appointed. Tafelmusik’s Music Director search committee, consisting of musicians, board members, administrative staff, and community representatives, has searched Canada and the world to identify possible candidates. Tafelmusik continues to work with candidates as guest directors to assess musical fit and chemistry, and to allow the orchestra to become better acquainted with them. Given the breadth of Tafelmusik’s repertoire, potential candidates must perform music from a wide range of eras with the orchestra. Tafelmusik will also continue to work with a number of guest directors who are not candidates, but who are a delight to welcome to the stage.”

Whether Glodeanu is one of the ongoing series of possible music directors or simply a guest, I cannot say, but it was a friendly stress-free performance of works by Venturini, Tartini, Vivaldi, J.S Bach and finally Rameau.

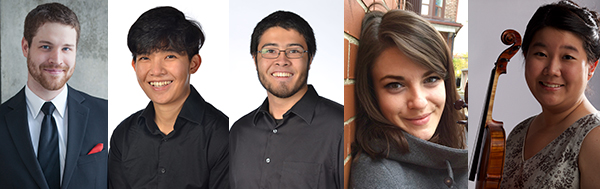

It was not a big glitzy event full of fanfare. This was intimate and very thoughtful. While they are all great musicians, they are first and foremost the nerdiest and most unpretentious lovers of what they do. They wear their hearts on their sleeves. And so they thanked their donors –who were the quiet audience—but not in the cheer-leading fashion we see at the TSO or the COC. There was more of a level playing field, the great artists speaking as equals to their family of donors, the people who really get them at a deep level, and who have committed to making important things such as tours, training programs & experimental programming possible.

Alison Mackay, bassist & visionary programmer

I was enormously impressed when Alison Mackay took the stage to speak about her special contribution to next season. In past seasons she’s offered creative programs that make older music brand new, showing us original ways of understand the relationship between music and its context in the lives of people from the past, with concerts such as House of Dreams and The Galileo Project.

Her next project may be the most ambitious and profound yet, namely Visions & Voyages: Canada 1663 – 1763 . Just as the COC & TSO are making special programming to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Canadian confederation (COC with Louis Riel, TSO with a promise of special commissions to Canadian composers, details still TBA next week), so too for Tafelmusik, via Mackay, who is almost like their artistic conscience. Instead of zeroing in on 1867 – a year far beyond the usual purview of this orchestra—they’re looking instead to a key century, bringing us context via the music that Europeans would have listened to in those key years of our past. I’m eager to see this project take shape, which is genuinely ambitious and visionary.

The season and this orchestra remain firmly rooted in the baroque, from their season-opener with Handel’s “Water Music”, a program of arias by Karina Gauvin titled “The Baroque Diva”, a program of works by other members of the Bach family than old J.S., and their annual Messiahs in December.

“Close Encounters” take Tafelmusik in a new direction with a series of chamber concerts on Saturdays.

It’s a happy coincidence that the orchestra are simultaneously seeking a new artistic director –since Jeanne Lamon’s departure—and commemorating the 35th year of their chamber choir led by Ivars Taurins, which (if I don’t miss my guess) means he’ll conduct a bit more than usual this season. In addition to Messiah we’ll be getting “Let Us All Sing! Tafelmusik Chamber Choir at 35”, a celebratory program in November 2016; “A Bach Tapestry” including the Mass in G Minor in Feb 2017; and Mozart’s C minor mass in May 2017.

Tafelmusik will also be touring extensively, to Asia in November 2016, USA in Feb-March 2017, as well as their participation with Opera Atelier in another visit to Versailles, this time to offer Charpentier’s Medée.

But in the immediate future? Beethoven’s Ninth in a series of concerts next week that will be recorded, making them the first North American period instrument band to have recorded the complete set of these symphonies.