Sometimes my need to explain myself leads to huge introductions that may confuse or perplex, pre-ambulations that happen both on foot and in the words of the blog.

As 2025 closes I escaped into recreation at the Red Sandcastle Theatre, where I took daughter & BF for a bit of escapism through Buster Canfield & his industrious fleas.

Eric Woolfe is the magician – puppeteer portraying Buster Canfield.

Before the show Zoe and I (plus the BF) talked about criticism, art and the meaning of life. Does that sound insane in this context? Or maybe to be expected.

Lately deep truths and Buster’s fleas share similarities, which is to say, they’re almost impossible to see, hard to find, perhaps not even there at all.

Speaking of escape: as I was talking their ears off about judgmental critics, Buster (Eric) worked his magic.

In the year since my mom’s passing, from time to time I think back to grad school & the study of theatre history in books such as Nagler’s Source Book, as I question the meaning & purpose of my blog, wondering if anything can be helpful.

I won’t make an awkward segue from the flea circus to something more serious, as this is normal for me, a stranger in a strange land. While I may write criticism my understanding of the word is different. I don’t judge, I don’t dismiss, and if someone’s performance is not good in my estimation, I will not write about it. I want to be positive, to be Pollyanna in saying only good things and avoiding negativity.

Funny today as I was listening to Vince Gilligan quoted on Q, broadcast by CBC today, I heard a call for more stories about good guys, while he seemed to lament the glamour of the bad guys.

I have to laugh but first let me quote Vince G.

“As a writer, speaking to a room full of writers, I have a proposal … I say we write more good guys. For decades, we’ve made the villains too sexy…. They say, ‘Man, those dudes are badass. I want to be that cool!’ When that happens, fictional bad guys stop being the cautionary tales that they were intended to be. God help us, they become aspirational.” (Vince’s full interview)

This is somehow new? Come on Vince, what about the readers mistaking Satan for the hero of Paradise Lost, written in the 17th century? No I’m not changing the subject, I’m saying that the same dynamic that gives us a preference for villains over heroes, also messes up our appreciation of the arts AND even worse, makes nasty reviews clickbait while positive supportive reviews languish in relative obscurity.

No this isn’t me lamenting the number of hits I don’t get.

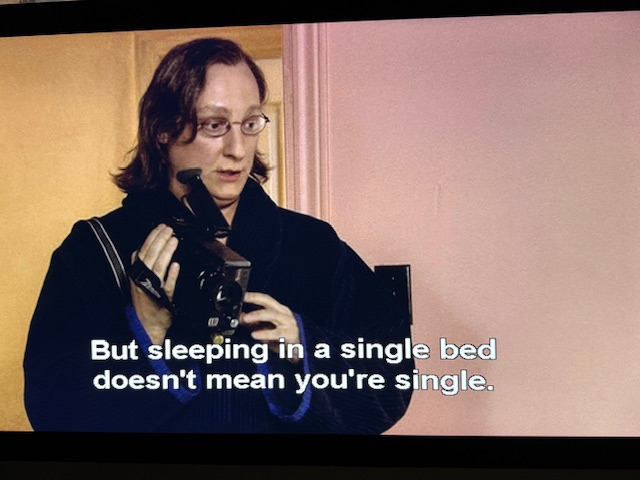

When I wrote about the recent presentation by Canadian Stage of Robert Lepage’s Ex Machina show The Far Side of the Moon, I was intrigued that they promoted it mostly as a nostalgic look at the space program with little mention of the autobiographical elements in the play.

And then I remember: that’s not Canadian Stage’s choice but the playwright’s. Maybe Lepage is reticent & shy even as he rips his belly open, showing us his entrails and flaws for us to examine. Of course he wouldn’t call it autobiographical but it’s obvious in its self-referential moments.

Isn’t it?

And I kept seeing a surprisingly rough tone in what other critics said about him, people taking shots at him in their assessment of the play. Lepage at one point speaks of narcissism, and if that weren’t sufficiently vulnerable, gets accused of being a narcissist. I saw a great deal (yes I later surveyed the reviews by others, long after I had written my own) about the technical prowess, with little apparent sympathy for what is felt in this show.

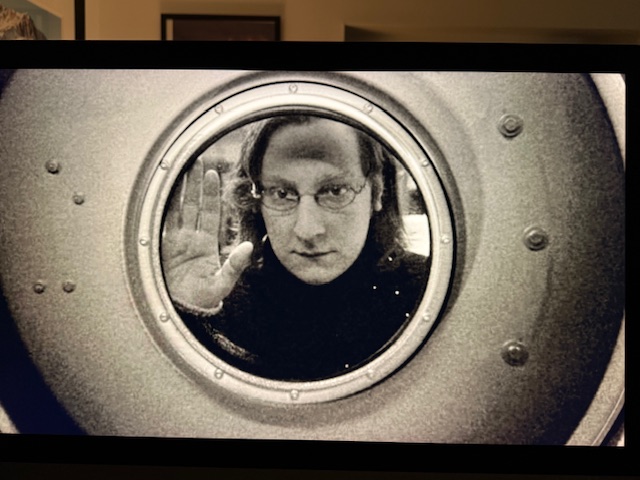

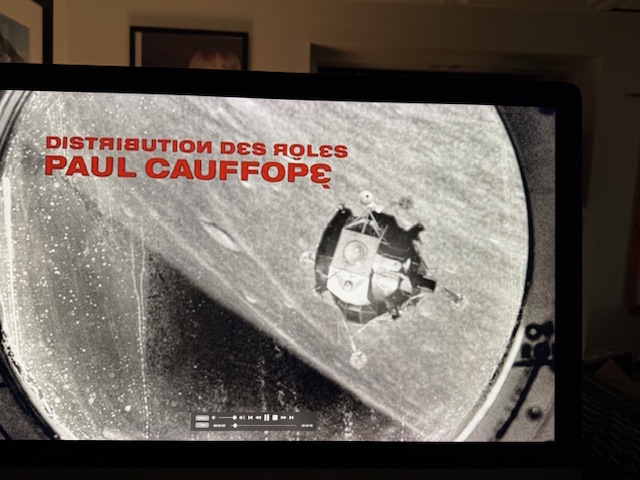

I say this after weeks pondering Lepage and his play, through the lens of the 2003 film version. When I heard that he’d filmed the play I got all excited and called up Bay St Video. I had hoped to buy it but dammit all, alas, it’s out of print. So I rented it for the week.

Watching Lepage’s film alongside 3 other non-commercial titles (Birdman, Klimt and War Requiem) had me thinking about the challenge of popularity, when some might mistake the box office returns for a true measurement of quality. Do I really have to say it? A film or an opera is not necessarily better just because lots of people went to see it. Box office is regularly used as an instrument to assess the success of commercial cinematic projects. And of course, there we go again, with a dynamic like the one with Satan in Paradise Lost. I am reminded of my frustration with Barbenheimer, when I loved Barbie and thought Oppenheimer was over-rated: but because of the usual response to their subjects, the comedy made money while the serious epic was treated as somehow better. I wonder if that verdict will persist.

Klimt & War Requiem, like Far Side of the Moon, were never going to generate a big audience, unlike the critically acclaimed Birdman.

I suppose I should not be surprised, especially when I read some of the reviews from other Toronto critics, mostly buying into the idea we saw in the promotional material: that Lepage is giving us a nostalgic glimpse of the space program. I suppose it’s clear to me he was employing those materials to talk about himself when we saw Lepage himself in the film playing the parts. Of course.

I was surprised to see so many who seemed indifferent, or maybe it was the decision that this time Lepage was not going to be given such an easy ride, perhaps resented because so many admire him. I know I admire him. I have to wonder if my experience is different because of what I have been through as a caregiver, and now mourning the passing of my mother, and subsequently observing her possessions and photos in the months after her passing. I want to again quote a line from Ex Machina speaking to this work that says “there is a sometimes thin line between the trivial and the sublime.”

As in 887 (another Lepage play I’ve seen a couple of times), a poem by another author is recited. 887 is subtitled “Or how does memory work,” and although Lepage dwells on memories of his life, he is also sharing the process of memorizing the poem “Speak White” by Michèle Lalonde. For Far Side of the Moon the poem in question is now about a mother and her aging, the focus of the play surely upon her death and its impacts upon her two sons. By splitting himself in two (as Philippe & André) Lepage is creating additional distance. But that doesn’t mean the work lacks feeling.

And so it now occurs to me that 887 is in some respects an elaboration of what Lepage did in Far Side of the Moon, where he uses a poem as a departure point for some of the observations made by Philippe, one of the characters. At first I was going to say 887 is deeper but no. 887 is merely easier to grasp because any Canadian can identify with it, whereas Far Side of the Moon might be more primal in its subject matter.

We watched Olivier Normand playing all the roles in 2025, roles originated by Lepage himself, including the mother and the doctor. In the film other actors play the mother and the doctor, but Lepage plays the adult versions of both Philippe and André. Watching the film I am more certain than ever that the imagery of the cold war space race are less nostalgia than the backdrop for an autobiographical meditation.

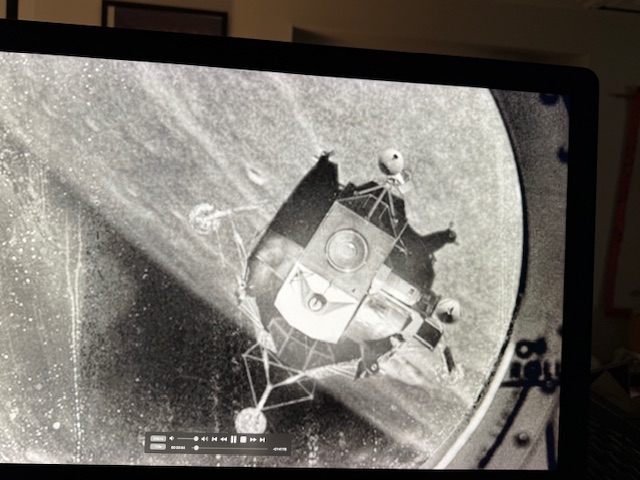

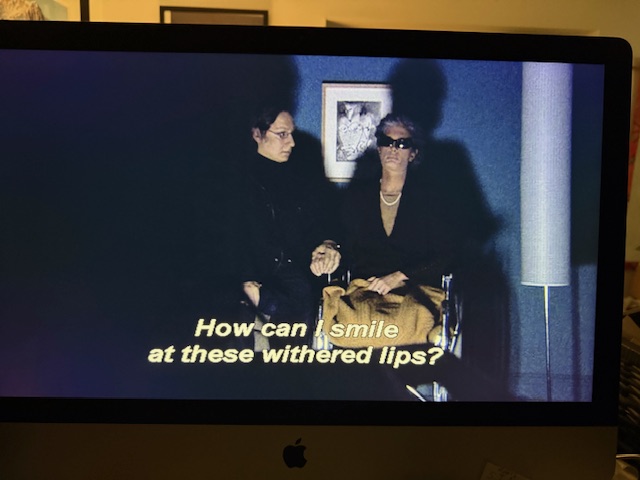

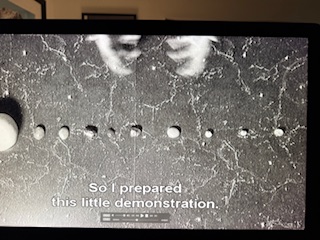

The images I captured from the video below show a stunning transition that I wanted to show that you see in the film.

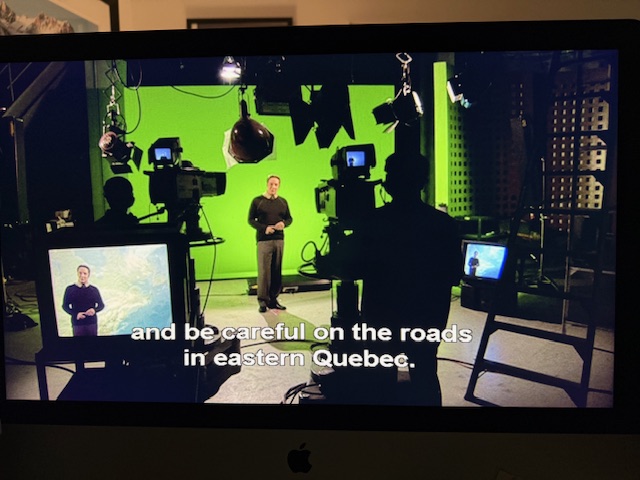

Then we meet André, Philippe’s younger brother, who is a weatherman on tv in Quebec, forecasting for the upcoming Christmas holiday.

The questions of reconciliation between USSR & USA are presented alongside the antipathy of two brothers, both of whom have a relationship with the sky, that in some ways encompasses the two sides of Lepage the artist. He’s both mainstream like André the tv weather man and a risk taker like Philippe the researcher.

Philippe has seen an invitation from television for video submissions to SETI, the international Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence project. You may recall seeing some of this in the film Contact, where an array of radio telescopes were trained on the sky listening for some kind of evidence of intelligence. What’s different in this case (in the film) was the invitation to create a message that would be sent out. That’s what Philippe was doing.

When André hears of Philippe’s project he jokes: you say nobody listens to you but now the whole cosmos will hear you.

Philippe would give the aliens a primer on humans living on Earth, a wonderfully oblique way to show us who he is. At one point Philippe offers a kind of roadmap for the hypothetical alien visitor searching for Earth, describing our solar system & the blue planet that’s the third from the Sun.

He is in the USSR for the conference where he misses his time to present. While there, he talks about poetry as the place where complex truths are captured.

He reads the Émile Nelligan poem Before Two Portraits of My Mother. Just as in 887 Lepage turned to an external poet to articulate a truth he wanted to echo or explore. On that occasion it was Speak white, a poem about the francophone experience in Canada. This time it’s a poem about portraits of mother. Need I repeat the obvious? Neither the play nor this film is merely about the space program. Here’s the poem.

BEFORE TWO PORTRAITS OF MY MOTHER

I love the beautiful young girl of this

portrait, my mother, painted years ago

when her forehead was white, and there was no

shadow in the dazzling Venetian glass

of her gaze. But this other likeness shows

the deep trenches across her forehead’s white

marble. The rose poem of her youth that

her marriage sang is far behind. Here is

my sadness: I compare these portraits, one

of a joy-radiant brow, the other care-

heavy: sunrise – and the thick coming on

of night. And yet how strange my ways appear,

for when I look at these faded lips my heart

smiles, but at the smiling girl my tears start.

Emile Nelligan (1879-1941)

I can’t help being a bit overwhelmed in encountering this, speaking as someone who has a house full of portraits of my mom, and who watched her smile bravely as she went from being the bold 80 year old to the bold 90 year old, the bold 95 year old (still driving her Honda civic), to the bold hundred year old using canes and then a walker, and then a wheelchair. I am also overwhelmed because I am frankly astonished that I did not read about this even once in responses to the play, but only in a comment from my dear friend Mary Walters, directing me to the text of the poem. (thank you Mary) The omission by critics seems rather huge, like a review of a Ring cycle opera that doesn’t mention that there are people singing. But come to think of it, that’s really apt, given that from what I see, they simply were un-moved, didn’t find Lepage’s imagery nearly as compelling as I have.

There’s a powerful scene when André looks at the the empty wheelchair in the home, one of the remaining pieces of evidence for his mother’s life. No words are needed. I shuddered at the image because it was literally so close to home for us. 2025 was the year of looking at the remnants, the furniture, the books, the clothes, and yes, even wheelchairs. Writing now as we come up on the anniversary of her passing I feel rather devastated. As I’ve been told, maybe it’s going too far to say that I’m moved to tears by something. I watched the film at least four times, plus a few extra views to capture the images you see in this blog. I hope Ex Machina / Lepage will forgive me. Indeed I forgive them that the film is out of print, which I find really upsetting.

Our understanding of objects changes with experience. I knew “wheelchair” differently, until I saw my mother in one, saw her struggling various times to get into or out of one, perhaps at the door to a hospital or doctor’s office. Looking at the wheelchair in this film complete with that cryptic Lepage expression is absurd in a Gustav Mahler sort of way, replete with comic overtones to tease you at a moment of enormous gravitas. Maybe my segue from the flea circus isn’t crazy at all.

I find the title brilliant, as I ponder the Far Side of the Moon as a meditative place. Pink Floyd had an album with a similar title that was among their best. I wonder if Lepage had to choose his title, mindful of copyright concerns.

Perhaps my reading of the film and play sounds odd. The thing is, here I am again, speaking about testimony rather than judgment. Yes the Canadian Stage production was a success, but I did not see any recognition of the play as autobiographical. I am not here to judge or assess Lepage, as good or bad, but to help with the digestion of his work, nor to judge the critics who saw it differently than how I saw it. A critique needs to be a digestive aid, like the rocks in a bird’s stomach to assist in breaking down / unpacking the work for others in the audience. The rocks are not to be hurled at anyone, neither the artists nor the critics who seem to love their villainous roles.

I wish those people who spoke dismissively of Lepage’s work on his play at Bluma Appel would watch this film, perhaps opening their hearts if not their minds. Maybe it’s because I’ve been tenderized like a veal cutlet pounded over and over by years of caregiving, challenged to empathize with the person in the wheelchair. I am sorting through the responses, intrigued but frustrated at dismissals from people who can’t seem to engage with what’s right in front of them. I suspect some of this is Lepage’s choice, perhaps reticent about laying himself bare and ready to allow the play to be misrepresented as a play about the space race, when it’s really all about him, the Quebecois artist confronting his two aspects, the commercially viable celebrity (like André the weatherman) and the risk-taking artist (Philippe who explores cultural impacts with his research). I wonder how fully he is reconciled to such emotions.

I hesitated before posting my comments about Lepage’s film, suspecting that my perspective may be distorted by the recent passing of my own mom. Or perhaps it’s the other way around, that I’m not a jaded reviewer inured to human pain, desensitized by having seen too many films.

I hope I never lose my sensitivity to the magic of artists, whether they’re working with fleas or wheelchairs. I am forever grateful, Eric & Robert. Thank you.