There’s a mystery underlying Edith Wharton’s play The Shadow of a Doubt. The text was just rediscovered by scholars in 2016, after sitting unproduced. There was almost a production in 1903 but it was cancelled.

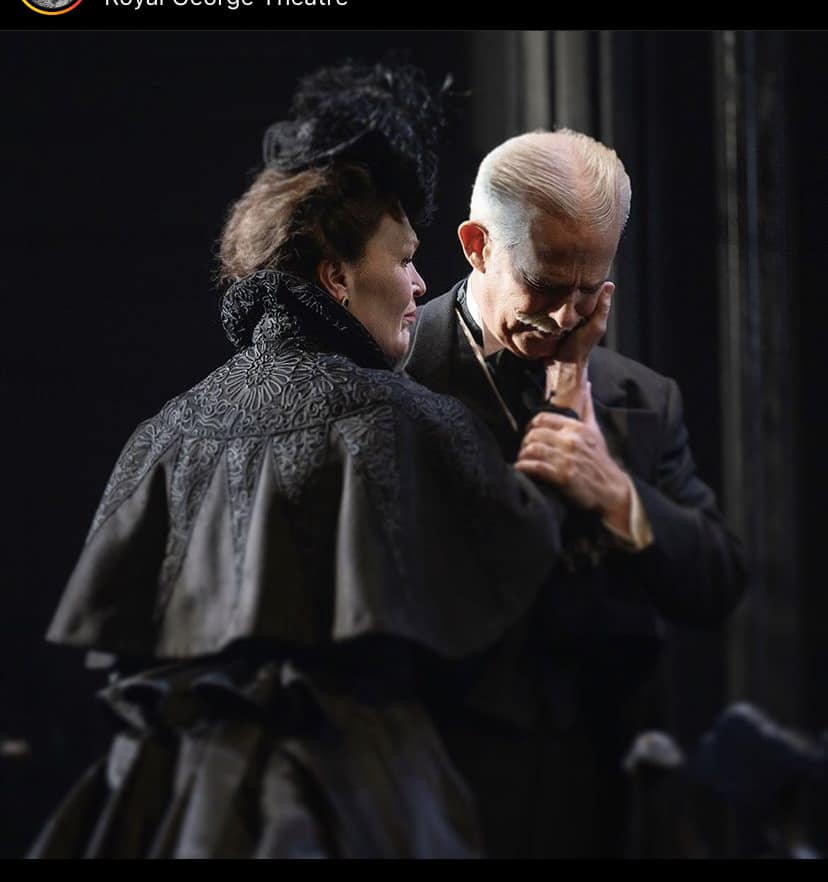

And now the Shaw Festival have produced the mystery drama, directed by Peter Hinton, a sharply drawn and authentic image of the early 20th century as seen in sets and costumes by Gillian Gallow. Truths lurk beneath a veneer of polite conversation between adults who rarely tell the truth. At times it’s as funny as a Feydeau farce or an Oscar Wilde manners comedy, full of wit and horny adults chasing one another around the stage.

Except that’s all against a backdrop of transgression, dark suspicions of sin that are not clarified until the very last moments of the piece, keeping you on the edge of your seat.

When Hinton wants us to recognize the gravity of a moment we’re presented with multiple points of view thanks to live video designed by video artist Haui. It’s as though we’re watching a live performance plus a documentary film at the same time, undercutting what’s being said, problematizing simple actions and statements. I remember seeing something like this in Robert Lepage’s auto-biographical 887, the video irresistibly changing the tone. Same here. It’s as though the video works like a push on the sustain pedal on a piano, to let the moment echo, washing into our ears and suggesting we rethink the moment.

At times there might be ghosts on stage, the secondary images of those we think we see, suggesting that perhaps we should not be so certain about what is before our eyes. Haui creates ambiguity in the concrete bodies performing the live performance, or in other words shadows of doubt.

In the photo below for instance one might wonder whose image is projected.

I wonder why we didn’t see this play sooner, why didn’t Wharton’s play come to light before now? It’s curious how the mystery surrounding the work in some ways parallels the questions raised by the work itself. There are many possible reasons, such as money or an actor no longer available: and we’re not likely to ever know the real reason with certainty.

Yet I’m inclined to think it’s something else as well.

This piece is far ahead of its time. There are some intriguing echoes of what we saw in Scorsese’s film of Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence, where a woman resists the gossipy forces of a conservative society, her own authentic woman. Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer) is unafraid of the strict conventions of New York society, drawing the attention of Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) , yet choosing to resist Newland, who stays with his wife May (Winona Ryder) until May’s death. Both Ellen and May are underestimated, perhaps like Wharton herself.

The woman defying convention in Shadow of a Doubt is saintly in her integrity, so much so that I wonder if Wharton had second thoughts about the credibility of her heroine. Kate Derwent (Katherine Gauthier), has not merely married above her class but is the bravest personage onstage. I won’t give it away except to say that I was moved to tears more than once and especially at the end. There is something of melodrama here, in the perfection of this heroine beset by the doubts raised by adversaries, whom she resists against all odds.

Please don’t think I’m seeking to cast aspersions on Wharton or her play by speaking of melodrama, a much maligned form still alive in cinema, whether acknowledged or not (and I’d say more about the musical component if I knew whom to credit, although I suspect it’s Peter Hinton). Wharton breaks the usual conventions by giving her heroine sufficient agency to defy her family when she sticks to her guns. As in the Scorsese film, the women are strong and under-estimated, each of them a source of truth.

We’re in that world of sharply barbed conversation, words that are often untrue, except when a woman such as Kate speaks. Kate was nurse to Agnes, daughter of Lord Osterleigh (Patrick Galligan). Agnes suffered a terrible accident and died. The details of that accident come out bit by bit through the play, one of the ways in which we become embroiled in the title of the play, recalling that one usually says something is beyond a shadow of a doubt: but not this time.

Lord Osterleigh gives us more and more subtexts, as he explains to Lady Uske (Tara Rosling) how he accepted and even promoted his daughter’s chosen husband, namely John Derwent (André Morin). Lady Uske is another truth-telling rebel albeit on a smaller-scale, married but honest. I found her so irresistibly outspoken as to seem to speak for the playwright herself.

Osterleigh complains to her that his son in law isn’t sufficiently ambitious, that he has married Kate a year after Agnes’s passing, and that Osterleigh fears that Agnes is forgotten. It’s not a fair statement though, as we see Kate encourage her step-daughter to honour the memory of her mother. What more could she do?

We’re in the comfortable world of rich people until the startling arrival of Dr Carruthers (Damien Atkins), who raises questions about the past, while softly blowing the lid off the play by reminding us of the real world. I wonder how much of this portrayal is in the script and how much might be aided by Hinton and a 21st century perspective, turning a figure who might have been played as villainous in 1903, but comes across as a figure evoking sympathy at least in the pathos of his entrance. Yet as the play unfolds he is but one possible candidate for the title “villain”, if we want to think in the old-fashioned terms of melodrama.

While some aspects of Wharton’s dramaturgy are very 19th century, such as her use of the devices of the well-made play, particularly the use of a letter to impact the plot, I’m inspired by her willingness to mix the snide remarks of superficial rich people with a sharp critique of that class.

I wonder if she or others thought this was perhaps too bold, too edgy to be produced in 1903. But it’s perfect for 2023, that’s all I know. For me the excellence of Edith Wharton’s play is beyond a shadow of a doubt.

There’s so much more I could say yet I’m afraid of giving it away. There’s magic in the unfolding of this story, continuing at the Royal George Theatre until October 15th. My chief doubt is that you would have any regrets about seeing it.

I love almost all the plays in this festival, and we have been going there every year for the past 15 years. This one was a disappointment. First, the visual solution to have all dressed in black, with black backgrounds, looks like a cry for originality by the director, but it doesn’t help perception. The fancy details of dresses are all lost due to the lack of contrasts in black-on-black. The colour could also differentiate between stories within the story – a loving couple, an old-friends couple etc, and the director missed this opportunity. They could just have black trim if they are desperate to put the play into a funeral mode. Second, the play was artificially stretched by musical pieces on the empty stage performed in unknown-to audience language (Celtic?), and this stretch of time didn’t pay at the end with a juicy resolution. Third, the resolution did sound like an unreasonable “screw you all” after all characters danced around the princess. If the author wanted to make a point about “trust matters”, then the director failed to underline it. Having four cameras projecting the faces didn’t add much and looked like another “try-too-hard” by the director. It’s too bad, considering it was a premier of so anticipated performance, and the actors (as always) delivered their best flawlessly.

Thanks for the comments!

I came to the play worried I’d have trouble following it, recalling that it took me a couple of times through to really get AGE OF INNOCENCE, even though it was a slow-moving film. I get what you’re saying (and arguably that approach of visual cues in the costumes is more apt for the style we associate with the period): but I suppose I’m accustomed to this approach in many operas I’ve seen of late, including the COC’s Macbeth (Verdi) a few months ago where I heard the same complaint. It’s always a trade-off, right? for me the focus created by an all-black approach must pay off or I’ll feel frustrated. But I was quite happy with this. I mentioned my liking for the music –even if I didn’t necessarily understand what was intended– for its assistance in shifting the tone: but of course ymmv, to each their own; and again, my taste (or reverence) for opera/melodrama has me patiently consuming the extra minutes (and also come to think of it, has me regularly sitting through arias in languages I don’t understand). But (speaking of melodrama) I’m conflicted about Oppenheimer, an overly long film without enough of a payoff for me. As far as the director possibly underlining a point, I like his gentler approach, given that the story as written seems rather harsh in how it makes that point (that “trust matters”).

Here’s a question to consider, that I believe I’ve already answered in my review. Did the Shaw Festival’s production (especially Mr Hinton’s direction) conceal or hamper the excellence of a great play? or maybe (as I believe) Mr Hinton et al improved and even redeemed a play sitting in a drawer unproduced because of the author’s misgivings.

Thanks again for commenting.

I suppose Mr Hinton and the whole team should be giving a credit for trying. Indeed, the play would be sitting in the drawer forever without it. However, not everything that any author produced is ideal or even good enough; some items are simply not finished. In these cases, I would grant a director a right to spin it into whatever they feel like, if it brings something deep. Here the ending was not deep at all: respecting the wish of a dying person about their privacy and decoration of their death (“Oh, I don’t want them to see me in such a bad state, so let’s hide it by fast death and you must carry the burden of this” – this wish does not deserve ruining life of others, its very narcissistic and childish). This spin only demonstrates the immaturity and narcissism of the author and doesn’t impress me as an audience member. However, the same story might be spun more into (for example) sex inequality, like in Anna Karenina: for example, the husband demanding full disclosure and himself hiding something from his wife. And the wife, meanwhile, in this hypothetical script, doesn’t make that much drama, especially at the end but resists disclosure in a more subtle way… Just a thought, of course. BTW, I still disagree with “black on black experimental decor, giving the audience a hard time comprehending what the black cat is doing in the dark room. The theatre is about the visual experience as much as about other senses, and lots can be done using colours, to get messages across…

Respectfully VM we’ll have to agree to disagree.