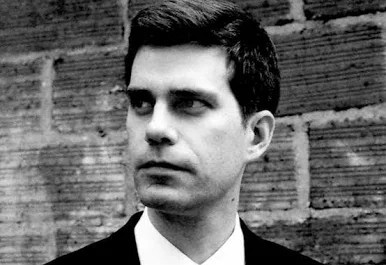

William Fedkenheuer is a Canadian violinist, fiddler, and educator, second violinist for the Grammy-nominated Miró Quartet recognized internationally for chamber music and performances at prestigious venues like Carnegie Hall.

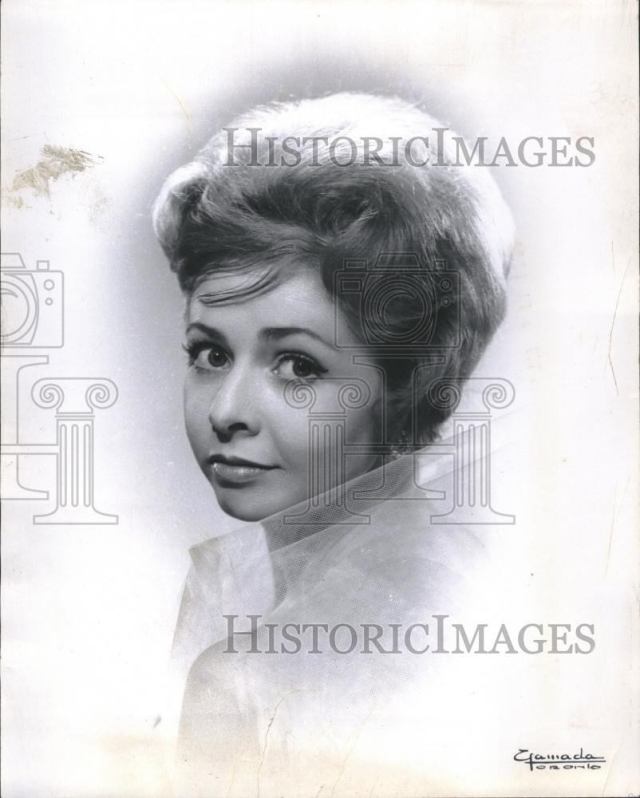

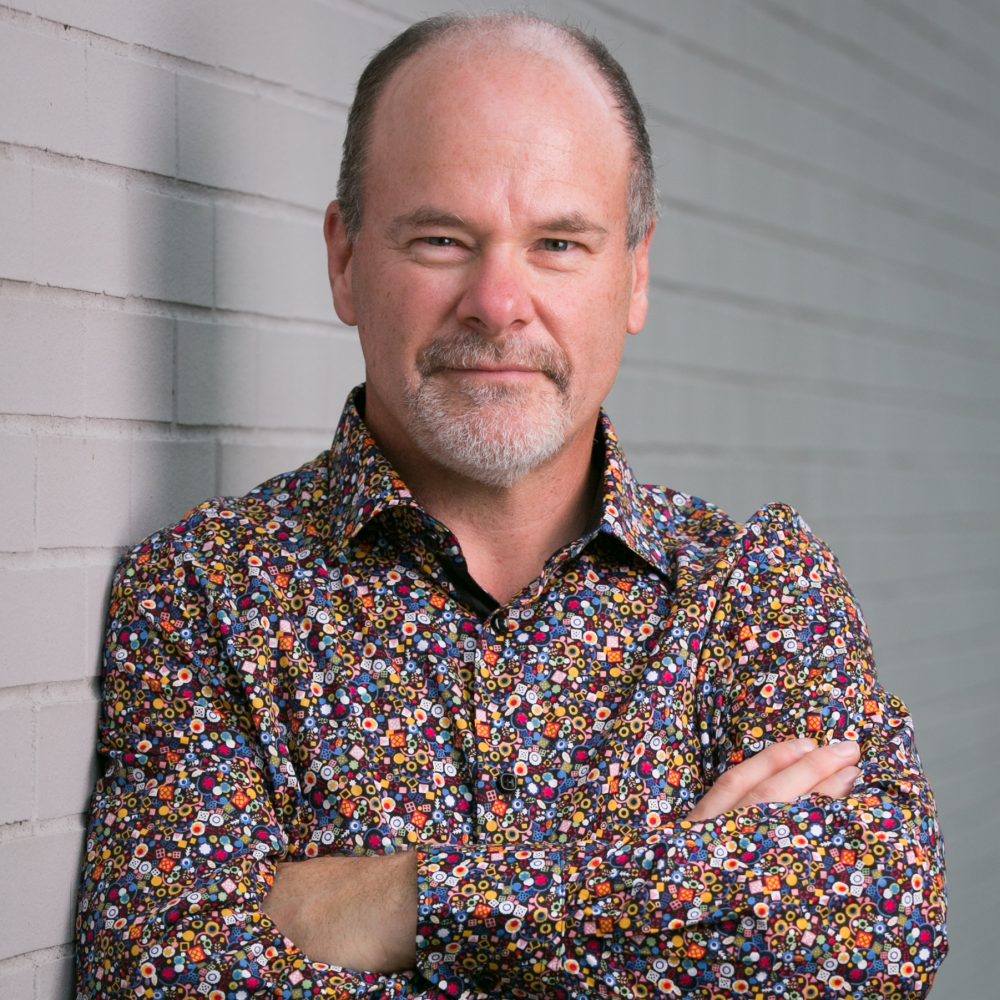

at the 2023 Festival (Photo: Lucky Tang)

William has begun his new role as Artistic Director of Toronto Summer Music, having succeeded Jonathan Crow on September 1st. Planning for the 2026 Festival is under way.

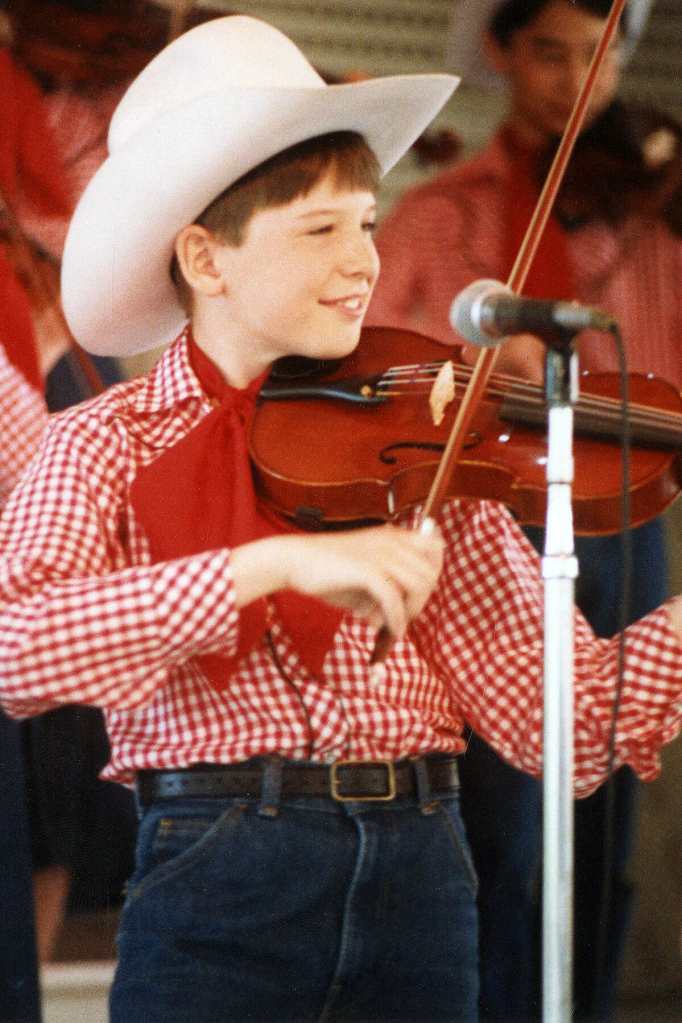

A two-time Grammy nominee with the Miró Quartet, he’s also a former Canadian National Fiddle Champion.

William is also a teacher known for his diverse career blending classical mastery with Canadian folk roots.

I was delighted to be able to ask William some questions.

*******

BB: Are you more like your father or mother?

William: I carry pieces of both of my parents, though in very different ways. My mother is where my warmth, curiosity, laughter, and desire for connection come from — she’s always approached people with openness and a sense of possibility, though there is fire in the belly! My father gave me steadiness and work ethic, the ability to stay focused and build things over time, and also that quiet recharge. He loved being outdoors in the beauty and silence of nature and I bring that into my life in my own way.

And then there’s the path they didn’t take: neither of them were musicians, but they encouraged creativity. If anything, I’m a blend of their values shaped by the unexpected world that music opened up for me. They both now sing in the church choir along with my sister, Liesel, who was in the Canadian Opera Company in the early 2000’s!

What is the best or worst thing about what you do?

The best part of my work — whether performing, teaching, or directing a festival — is witnessing transformation and impacting a life. A concert that changes the room or the individual. A student discovering a new part of themselves. An ensemble growing into its artistic identity. A concert space that opens into each individual’s moment of choice.

The hardest part is the pace. The artistic world is 24/7 — travel, rehearsals, emails, programming, planning seasons years ahead. Finding balance while trying to give my full self to each role is both a joy and an ongoing negotiation and you can ask my wife, Leah, and my boys – Max and Olli, how that’s going!

Who/What do you like to listen to or watch?

I listen widely — classical, fiddle traditions, singer-songwriters, jazz. I’m as happy diving into a Beethoven quartet recording as I am listening to The Fretless, or whatever folk or roots band someone just introduced me to. Love me some Garth Brooks, Dolly, or Gordon Lightfoot! When I unwind, I lean toward shows and stories about creativity, craftsmanship, or human problem-solving — and, occasionally, a good murder mystery.

I also love silence – which may be unexpected to some. There are a lot of demands on the extrovert side of Will, and there is something so special about the stillness of silence, breath work, and meditation. One of my favourite moments in time is that split second of absolute silence right before a concert performance begins.

What ability or skill do you wish you had, that you don’t?

I wish I had a better skill for slowing down time — the ability to pause, take stock, and savor a moment just a little longer. As musicians, we spend our lives shaping time, pacing emotion, and stretching a phrase to its fullest meaning, yet life outside the concert hall moves at its own unrelenting tempo and rarely stops! I often catch myself wishing I could bring the same spaciousness, intention, and breath to the rest of my world that I strive for onstage.

When you’re just relaxing and not working, what is your favourite thing to do?

Cooking with my family and settling into long conversations around the table is one of my greatest joys. I love being outdoors, wandering through a new city with no agenda, and taking our dogs, Lola and Frizzy, out for a good walk. And honestly, ending the day watching Murder, She Wrote and eating freshly popped popcorn with my youngest son, Olli, has become one of life’s sweetest reset buttons.

What was your first experience of music?

My earliest musical memory is sitting in the living room during my sister’s violin lesson in Calgary, absorbing everything by osmosis — and constantly being distracted by the puppies that had just been born that lived there. I also loved going to the Calgary Philharmonic Pops concerts; they were pure joy for me, and I treasured my growing record collection and whatever we could find on the radio. My first teachers blended fun and focus in a way that felt magical, and that balance became the foundation of my entire musical life. Loved my Hooked on Classics albums!

What is your favourite melody / piece of music?

It’s impossible to choose just one — but Beethoven’s Cavatina from Op. 130 has been a lifelong companion, and so has the fiddling tradition I grew up with – there is nothing like the Orange Blossom Special and an audience to share it with. Those two worlds shape the way I hear everything. And truly, anything from Mozart to Drake, (dare I say Justin Bieber?), I can go old school or new, can lodge itself in my ear and stay there for days — if it’s honest and beautifully crafted, it finds a home.

Do you have ideas about modernizing classical music culture for modern audiences?

Absolutely. At its heart, I think audiences today are looking for connection — for humanity. When we offer transparency, storytelling, interdisciplinary collaboration, diverse artistic voices, and programming that genuinely reflects the world around us, we invite people in rather than asking them to observe from a distance.

Festivals like TSM have a real opportunity to model this: bringing established and emerging artists into the same creative space, bridging genres when it deepens the experience, and treating concerts as shared moments rather than rituals of correctness. TSM already has such a close, vibrant community, and it’s an extraordinary gift to step into a role where that spirit can grow, evolve, and welcome new audiences in meaningful ways.

You are both a violinist and a teacher. Talk about your background training and how you got here.

My path has been shaped by extraordinary mentors and ensembles. I grew up at the Mount Royal Conservatory in Calgary, studying with Joan Barrett and Edmond Agopian, and later with Kathleen Winkler at the Shepherd School of Music at Rice University. I spent a brief but formative time at Indiana University with Miriam Fried before stepping directly into the world of string quartets — first with the Borromeo, then the Fry Street, and now the Miró Quartet.

Teaching has been woven into my life just as deeply as performing. I coached my first chamber music group as a senior in high school, and it opened a door I never closed. There is something profoundly meaningful about sharing what I’ve learned and helping others discover their own artistic voice. At The University of Texas – Austin, I teach violin, chamber music, and professional development, guiding musicians as they build lives that are both artistically rich and sustainably crafted.

Every chapter — competition wins, more than 1,700 concerts around the world, Grammy-nominated recordings, commissions and premieres — has reinforced one truth for me: artistry and education are shared lanes. They feed each other. One of the places that comes alive most vividly is in TSM’s Regeneration concerts, where mentors and fellows share the stage on Saturdays. Those moments capture exactly why I do what I do: music as craft, connection, collaboration, and community.

You have been both a fiddler and a violinist. What do those words mean to you?

As a fiddler, I learned instinct, groove, improvisation, and the joy of playing for people in community spaces. It taught me how to read a room, how to bring an audience in close, and how to take the whole place on a ride where everyone feels part of the story. As a classical violinist, I learned precision, depth, structure, and a different kind of connection — one rooted in long-form storytelling, nuance, and emotional architecture. It reaches people just as powerfully through a very different pathway.

Neither identity replaces the other – they inform each other. Fiddling gave me freedom and instinct; classical playing gave me depth and language. Together, they’ve shaped a wide emotional landscape that feels like home — two traditions intertwined, each making the other more alive and having tears and joy always along for the ride.

Is there anything one learns as a fiddler that resonates in the classical world?

Absolutely — everything. Fiddling was my first musical home, the place where I learned to step into the spotlight with comfort, spontaneity, and a real sense of play. It taught me how to read a room, how to trust my instincts, and how to live inside a deep internal rhythm that comes from the body as much as from the ear. In the fiddling world, there isn’t really a concept of “mistake” — you can change a note, reshape a phrase, improvise your way forward, and you’re always only one note away from making it sound like you meant it… or discovering that you did. That freedom becomes a way of breathing onstage. Those skills translate beautifully into classical performance, where authenticity matters just as much as virtuosity. Fiddling gave me the courage to be present, to react in real time, and to trust the connection between performer, colleagues, and audience. It opens up a different kind of expressive world — one that enriches everything I do in classical music.

Talk about your teaching philosophy.

My teaching rests on one principle: anything is possible.

Students learn to uncover their unique voice by developing the tools, mindsets, and curiosity to shape their own path. I focus on lifelong learning, self-awareness, strategic thinking, and empowering each artist to build a career that reflects who they genuinely are. My role is part teacher, part collaborator, part guide — helping them understand what’s possible and giving them the structure and support to reach it – in all areas that are meaningful in building a life in music and as a human.

What are your thoughts on the TSM Academy and the importance of teaching?

The Academy is one of TSM’s greatest strengths, the heart of what we do, and what sets us apart. It brings emerging musicians into direct, meaningful contact with world-class artists in an environment built on collaboration, curiosity, and the discovery of one’s artistic voice. It’s not just instruction — it’s immersion. And it was the most impactful single experience that I was privileged to do – only twice – when I was the age of our fellows.

For me, teaching is tied directly into performance. It’s how we pass forward the values, traditions, and humanity of this art form, and how I grow and learn as a performer myself. The Academy allows us to shape the next generation while weaving them into the living fabric of the festival itself — something uniquely possible at TSM. Nowhere else do you see strings and piano fellows, vocal artists through the Art of Song program, and community players all learning, rehearsing, and performing side by side. And the mentors are growing from this interaction with the fellows and master artists of tomorrow. It’s a rare and remarkable ecosystem — and one of the things I’m most proud to help nurture.

Do you have anything you can tell us about the Toronto Summer Music Festival?

TSM is heading into a wonderfully exciting chapter — one that blends its rich history with fresh artistic ideas, wider community reach, and programming that speaks to the world we live in now. I’m having a great time shaping a festival that brings extraordinary artists to Toronto and builds new ways for audiences, students, and musicians to connect with one another. I can’t spill all the secrets just yet… but our season announcement is late February, and there’s a lot I can’t wait to share. Sign up for the mailing list now!

Do you ever feel conflicted, reconciling the business side and the art?

I actually see the two as complementary. The art is the heart of what we do, and the business provides the structure that allows that art to reach people, sustain itself, and grow. When the business side is aligned with the artistic vision, it becomes a powerful tool — one that amplifies creativity rather than constrains it.

In fact, the practical skills behind the scenes are often what allow artists to build meaningful, long-lasting careers. A strong foundation — whether it comes from our own training or from a great team around us — helps turn artistic ideas into real opportunities, real connections, and real impact. When art and business work together with clarity and purpose, they create a pathway where artists, audiences, and organizations can all thrive. My hope is that we keep inviting more openness into these conversations, tending the alignment between art and structure in ways that support our work, our artists, and our communities.

What can classical music learn from how popular musicians play & market their music?

Connection is paramount. Popular musicians speak directly to their audiences — emotionally, culturally, and generationally. They lean into instinct, vulnerability, storytelling, and authenticity, and their audiences feel seen in the process.

Classical musicians can embrace that same spirit while amplifying the depth of musical connection we already offer. We can communicate more openly, program with greater intention, and invite listeners into the world we’ve dedicated our lives to — not by simplifying it, but by humanizing it.

Classical music is literally everywhere. People encounter it in films, commercials, games, and cultural moments of every kind. We often know more of it than the cultural narrative suggests. When we highlight those connections — the shared emotions, the universal stories, the impact a single phrase can have — we meet audiences where they already are and open the door even wider.

Debussy and Wagner both spoke of the virtuoso as a kind of circus animal… does this influence how you perform or teach?

I think of virtuosity as freedom — the ability to express anything without limitation. And truthfully, I often wish I had even more of it. I’m most interested in virtuosity that performs with people: the kind that opens the door to deeper listening, bigger emotions, and more vivid storytelling. When technique becomes effortless, it frees the artist to be imaginative, daring, and deeply connected. That’s what I try to teach: virtuosity as a platform for meaning, not a destination. At its best, it becomes one of the most powerful tools we have for creating unforgettable, transformative moments. And sometimes, the simple act of being in awe is an emotion all its own — a reminder of one reason we make music in the first place!

Live or recorded performance? And how do you make recordings feel “live”?

Live performance is irreplaceable — the shared breath of a room, the immediacy, the risk, the community. You feel people leaning in. You see the interaction onstage: an eyebrow raised, the curl of a smile, the choice not to look at one another. All of those tiny signals let the audience into the inner life of a piece. Chamber music, especially, lives in that visible, palpable conversation between musicians.

Recording asks for a different intimacy. To make a recording feel “live,” I imagine playing for someone I care about — one person, right in front of me (over and over!). We often invite friends and colleagues into the physical space, in person or even over Zoom, because the moment another human is listening, the performance becomes more alive. That simple shift keeps us human, connected, and grounded in communication rather than perfection.

Both forms have their own magic. Live is about shared presence; recording is about distilled connection. But in both, the goal is the same: to make the listener feel like they’re part of the story.

If you could tell institutions how to train future artists, what would you change?

I would broaden our definition of success to reflect what musicians’ lives actually look like today.

That means teaching artistic identity, communication, community engagement, financial literacy, mental health strategies, and long-term career architecture — alongside technical and artistic excellence.

Musicians need more than skill; they need purpose, adaptability, relevance, and a sense of belonging in the wider world.

A few years ago, during the quiet of the pandemic, I wrote a post that struck a chord with thousands of musicians. It came out of years of research and more than two decades of performing, teaching, and watching colleagues build full, meaningful careers. It still captures what I believe about how we can evolve our training for the next generation —

Link: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1DE3U7rsgN/

What teachers or influences were most important to your development?

Joan Barrett at Mount Royal, Kathleen Winkler at Rice, Robert McDonald at Juilliard, and Tom Novak at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center have each played formative roles in my artistic development and have become close friends and mentors along the way. Their guidance has shaped so many of the threads that continue to define a life and career in chamber music.

Equally meaningful are mentors outside the traditional artistic sphere. Tom Delbanco — the John F. Keane and Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center — has profoundly influenced my thinking around leadership, character, team building, and purpose. A lifelong community musician who grew up surrounded by many of the great artists of the past century, Tom has become both a dear friend and collaborator, and our musical adventures together have been among the most fulfilling of my life.

Each mentor, in their own way, has helped shape my curiosity, discipline, artistic integrity, sense of community, and belief that music can have genuine human impact. I’m deeply grateful to them all — they are woven into everything I do and into the lives of those I’m privileged to reach through music.

*******

William Fedkenheuer is planning the next Toronto Summer Music Festival that begins July 9th 2026. The season announcement is coming in February…(!)