No one left the IMAX theatre for the three intense hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer.

Nightmare images that night reminded of my childhood, portents of the end of the world as I tossed and turned.

Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin, the two authors of the Pulitzer Prize winning book American Prometheus collaborated with Christopher Nolan on the screenplay, which should guarantee accuracy.

Is that all we need for a great film? There’s something crucial missing for me.

I can’t help putting Nolan’s Oppenheimer alongside the other two great works in my head pertaining to J Robert Oppenheimer. One is Doctor Atomic (2006), the opera with libretto by Peter Sellars and music by John Adams. The other is Roland Joffé’s Fat Man and Little Boy (1989), a film co-written by Joffé and Bruce Robinson with music by Ennio Morricone.

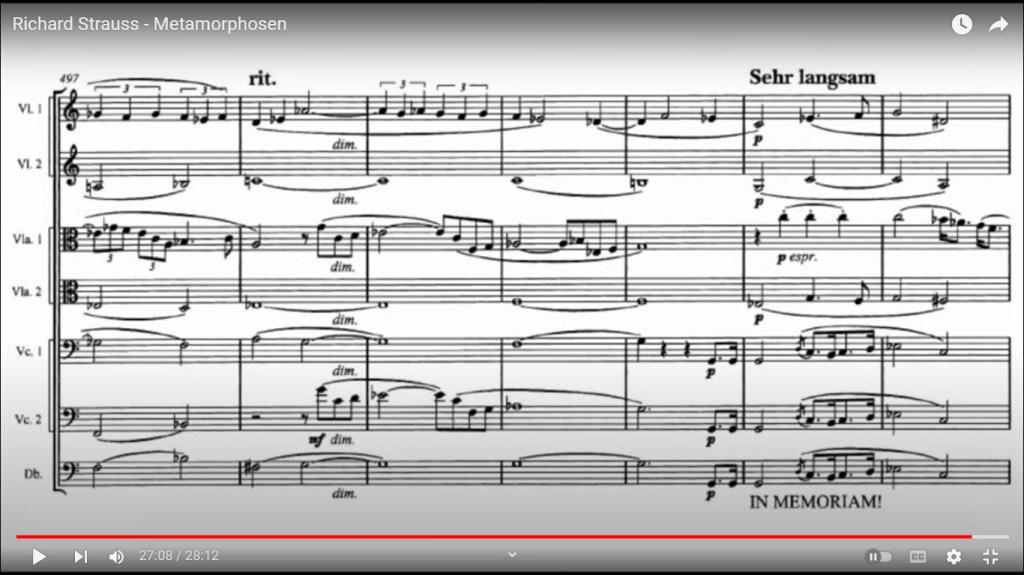

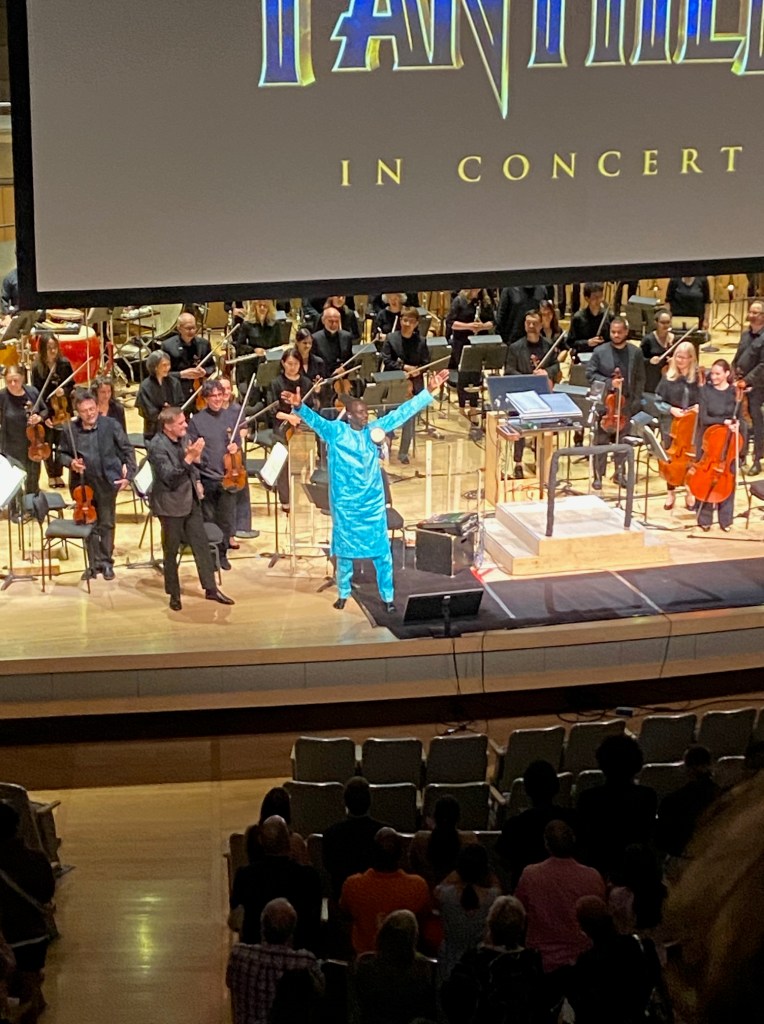

I strive always to be positive, so maybe if I speak of what I love from Adams/Sellars and Morricone/Joffé/Robinson, perhaps I will understand why I’m unhappy with what Nolan/Bird/Sherwin have done with academy award winning composer Ludwig Göransson, whose work I loved just a few weeks ago in Black Panther. As I re-play samples of his music via youtube I am both impressed yet left cold, as that’s perhaps my predominant emotion. There needs to be something more in a three-hour film. I think there’s something literal-minded and sterile in Oppenheimer. Yes we know the atomic bomb is lethal, that the H-bomb that much worse. Oppenheimer has a lot more to him than what we see in this film, and I point to Adams and Morricone, who managed to make more human portraits of Oppenheimer than what we get in the new film. Yes it’s big and loud and supposedly authentic, yet that’s not really the only criterion for a biography.

I’m reminded of the two version of Otello, one by Rossini, one by Verdi. Neither of them presents all of Shakespeare’s story and each one distorts elements of the plot: but in the interest of moving us, making us cry, making us care. That’s what I miss in Nolan’s film, and I will illustrate by looking at Adams and Morricone.

We know that Oppenheimer called the test site “Trinity” via a John Donne sonnet.

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp’d town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

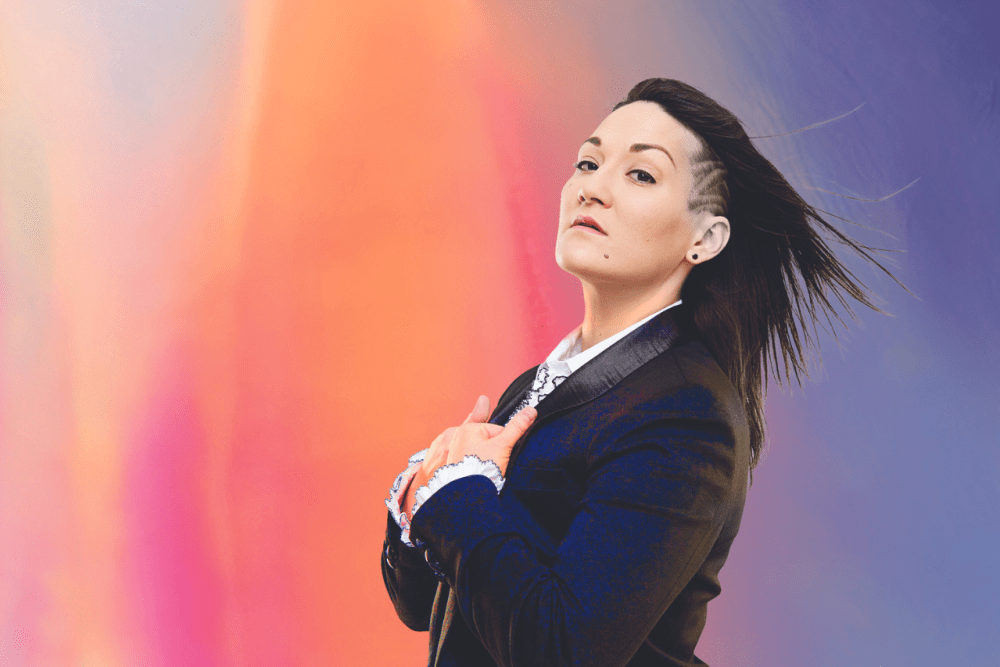

The best thing Sellars and Adams do is to make this sonnet into an aria sung by Oppenheimer at the end of the first act of the opera. Here’s Gerald Finley singing the aria. Sellars takes the words that might seem most pertinent to an atomic bomb namely “break blow burn” and repeats them for extra emphasis.

There’s nothing in the entire 3 hour movie as powerful as this.

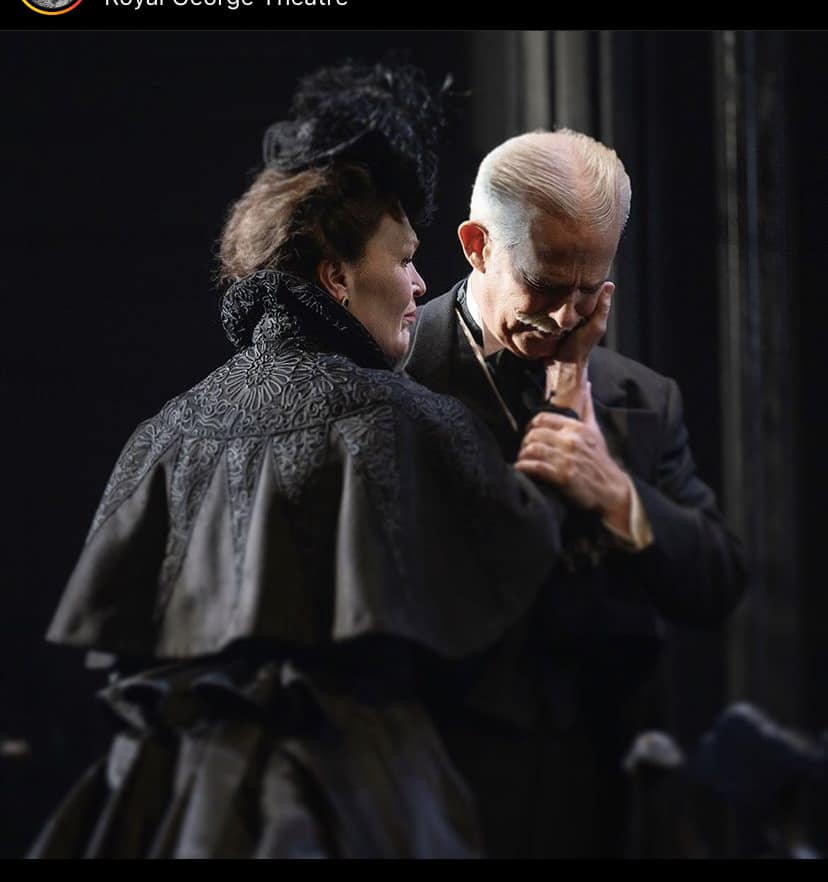

I’m intrigued lately with melodrama, a form that keeps reasserting itself in various places such as the Shaw Festival production of The Shadow of a Doubt that I saw recently. If we accept that the essence of melodrama is music with words, and a lack of agency for the principals, we can’t help noticing how melodrama persists in our culture in new guises. The aria Finley sings is passion without agency, not so very different from the despairing tone of the Miserere in Il Trovatore from the middle of the 19th century.

Ennio Morricone is one of my favorite composers of film music. He often creates set pieces within a film that lend themselves to concert excerpts, not unlike the way arias get excerpted from opera. Morricone’s music from The Mission, another collaboration with Joffé, also has several such set-pieces. Morricone’s music for The Untouchables (1987) has a few recurring themes that director Brian de Palma employs for brilliant effect. There’s a heart-rending melody we hear when Sean Connery’s character Jim Malone is dying that recurs later when Eliot Ness (Kevin Kostner) gives Malone’s lucky medallion to the new guy (Andy Garcia) who will carry on, a stunning moment. There is also a theme of triumph heard in the courtroom when justice is done, that we hear again as the film ends.

But let me keep the focus on Oppenheimer by looking at a film I regularly see under-rated, even dismissed, Joffé’s Fat Man & Little Boy. I’ve watched it three times this year, and will probably watch it again this week after writing this. No it is not as accurate as Nolan’s film, but then again I enjoy Verdi’s Otello more than most productions of the Shakespeare play even if it departs from the original text. I think fidelity is over-rated. I’d like to offer a quick comparison on a few fronts, just to suggest why I’d prefer the 1989 film to the 2023 one.

General Leslie Groves is the powerful figure behind the creation of the atomic bomb, portrayed by Matt Damon in the current film and Paul Newman in Joffé’s film. Damon is closer in size, given that Groves was actually 6’3” and over 230 pounds. But Joffé and Robinson suggest that Groves is really in control, subtly manipulating Oppenheimer with his secret love-life and political affiliations, verging on blackmail. The recent film may be accurate but we don’t get the same sense of Groves as the power behind the project, indeed Damon’s portrayal is kind of light-weight compared to the nasty fervor Paul Newman gives us. This profile of Groves from the Atomic Heritage Foundation suggests that Newman’s portrayal was if anything too gentle, and that his importance is under-estimated.

Jean Tatlock is the other woman in Oppenheimer’s life, a lover with whom he met even after the beginning of the Manhattan Project. There’s a quote I saw on IMDB that suggests how wrong the new film is.

J. Robert Oppenheimer : Why limit yourself to one dogma?

Jean Tatlock : You’re a physicist. You pick and choose rules? Or do you use the discipline to channel your energies into progress?

J. Robert Oppenheimer : I like a little wiggle room. You always tow the party line?

Jean Tatlock : I like my wiggle room, too.

I read the phrase “party line” in terms of Tatlock’s politics, her association with the communist party. It’s a very 21st century reading, that seems deaf to the realities of the 1930s, when one might have sympathy for the cause of the Spanish Civil War or a trade union without actually being a card-carrying member of the communist party. Yes in the 1950s we have a full-out red scare and black-listing of people in the entertainment community like Zero Mostel or Dalton Trumbo. In the new film it’s hard to see that there’s anything between Tatlock and Oppenheimer, even if he does have sex with her. It’s rather clinical in its presentation of her suicide. I don’t think I like this version of Robert Oppenheimer, he’s not very nice.

On the other hand, there’s the way Morricone, Joffé and Robinson approach Jean Tatlock who becomes a symbol in the film, and for me seems far closer to the likely reality of how she figured in Oppenheimer’s life. Portrayed by the luminous Natasha Richardson, she is a beautiful reminder of an earlier chapter in Oppenheimer’s life, and this time yes he’s smitten, and no wonder. He may have moved on to Kitty (Bonnie Bedelia in this film, Emily Blunt in the newer film), but Tatlock has a special place in his heart. I think Joffé would say that the Oppenheimer who knew her earlier was more idealistic, that he has now sold out in a sense through his relationship to the project. When he gets the letter that she has died we hear her theme.

She has killed herself and it feels as though part of Oppenheimer dies too. No it may not be accurate, although it’s emotional music with a powerful impact. I’d rather have the romantic music of Morricone trying to suggest a deeper meaning, and a conflicted Oppenheimer than the creepy cold approach of the new film, that’s never fully alive in the first place.

Bodelia’s Kitty and Newman’s Groves see eye to eye in their pragmatic understanding of Oppenheimer. She’s drinking heavily, he’s rolling his eyes, yet each gets what they want.

It’s a rather powerful moment whether or not it’s in any way verifiable. But this is what I love in this film, that we’re seeing real human interactions that make sense. We will later see the triumphant reception in America when the war ends, and watch how Leslie Groves (Newman) quietly sees Oppenheimer sucking up the acclaim for his success, loving his celebrity.

Robinson & Joffé create a fictional character who might be the star of the film, my favorite character. Michael Merriman is portrayed by John Cusack, a scientist who also plays baseball and goes riding with Oppenheimer. He has a bad habit of rushing to rescue people without considering his own safety, which works okay the first time we see it (and gets him the attention of a nurse played by Laura Dern), but will lead to his death, when an accident during a test with a radioactive isotope gives him a fatal overdose of radiation.

No we won’t see what happens in Japan when the bombs are dropped, but we do see what happens to Michael, giving the film some balance and extra commentary on the project. Michael has been writing a diary that is a premise for his narrating chunks of the film. But our narrator is going to die.

I realize in hindsight (meaning something that hit me in the night) that although I’ve titled this “Three Oppenheimers” I only spoke of one, namely Gerald Finley. I said nothing about either Cillian Murphy (our 2023 Oppy) or Dwight Schultz (from the 1989 film). I recognize that the picture immediately above, showing the cover of Fat Man & Little Boy tells you something about that treatment of the story: that Paul Newman as General Groves was really the star, which works for me. Cillian Murphy may have given a brilliant performance of the lines he was given but I found him to be a cipher, an enactment of a mathematical concept, which is another way of saying, I really don’t get who he is in this film. Perhaps that’s true to the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, which seems to work very hard at being accurate (at least so far in my reading). I will have to watch Oppenheimer again, and perhaps that will alter my opinions. I’ll be seeing the Joffé film again in the next couple of days, perhaps Wednesday.

I think I prefer melodrama in my films. I love the Star Wars films, the Lord of the Rings films, Tim Burton’s Batman films, the best science fiction such as 2001 or Blade Runner, all of which employ music for the most brilliant moments. I’m sad to see that this seems to be increasingly rare. While there’s powerful music in the Christopher Nolan Batman films (that I like), the music isn’t melodramatic but more subtly supportive of the film. It means that when you hear excerpts of the score later , for instance in a concert, you’re not moved the same way. Similarly Göransson’s music for Oppenheimer is as subtle as the film.