Toronto Summer Music’s theme is the same as the title for last night’s concert, namely “metamorphosis”. I’m writing about it Saturday on the closing weekend of the festival.

I’ve been pondering that word over and over in response to the concerts I attended, last night being my fifth. I’m thinking that maybe metamorphosis is a good word to describe both the process of music and the making of musicians, the dual missions of TSM. Their Academy overlaps their performances, the artists’ teaching a natural extension of their virtuosity. It was delightful to stand in the lobby chatting with Carl Lyons (another TSM regular) about the institutional aspect of TSM, the way that one feels one is in the presence of a school and its mission, even as we walk the halls of those other schools where TSM takes place, namely Koerner Hall at the Royal Conservatory of Music and Walter Hall in the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music.

Every concert has had its surprises, the unexpected moments and last night was no exception.

There was the laughter before we began the Brahms piano trio, when violinist Andrew Wan fidgeted, unready to start and showing his dissatisfaction with his piano bench, dashing into the wings to find a replacement. Then pianist Michelle Cann gave us the punchline when she quipped that benches really should be for pianists only. Were the ones giggling and applauding (like me) also pianists? That was at a moment when the audience were already eating out of the performers’ hands, having already been thrilled by the first part of the remarkable program:

Poulenc: Sextet for Piano and Wind Quintet, FP 100

R. Strauss: Metamorphosen, (arr. Rudolph Leopold)

(intermission)

Brahms: Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8

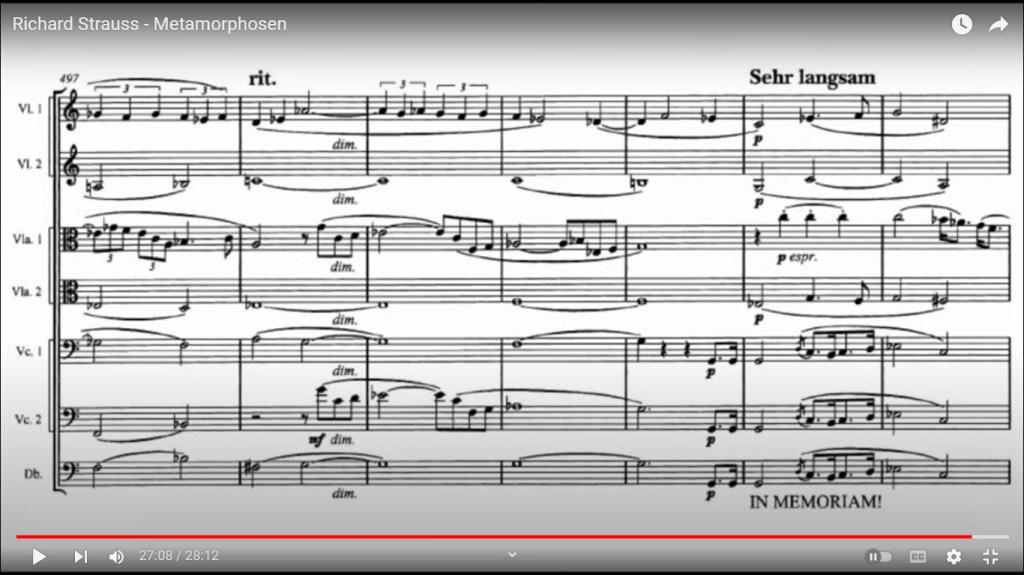

I was drawn to attend this concert by Richard Strauss’s famous piece for 23 solo strings, not realizing that instead of ten violins, five violas, five cellos, and three double basses, we’d encounter the work in a purer form, with seven players, namely pairs of violins, violas, cellos, plus a single double bass. Surveying the score via youtube it seems that this arrangement doesn’t actually omit anything, as there appear to be seven lines. Perhaps I’m missing something, but this arrangement seems to be a perfect paraphrase except for the matter of size.

Aha, how ironic to think that we heard a version of Metamorphosen that was itself changed, undergoing another metamorphosis. Even in its original form it’s a long series of changes, twists and turns, as though we watch a loom weaving strands into a tapestry before our eyes.

How interesting to ponder whether this was truer to the essence of the piece, a kind of ideal as we might imagine inside the composer’s head. The title telling us that this is a study for 23 solo strings has always suggested to me that there are 23 voices. But what if you take Strauss’s work and really force each part to play a solo line: which is exactly what we heard. That’s what Rudolf Leopold’s arrangement does.

I hope I have identified the players correctly. The one tiny thing TSM doesn’t do is clearly identify who is playing what in the program, which is likely more of an issue for a blogger than a listener. Still I want to be sure I’m giving credit to the right personnel:

violins Aaron Schwebel & Sheila Jaffé, violas Keith Hamm & Rémi Pelletier, cellos Leana Rutt & Emmanuelle Beaulieu Bergeron, and Michael Chiarello, bass.

It’s exposed. It’s still as densely constructed, but now we see every line and its answers unfolding before us not unlike the way the score lays a piece bare. In the intimacy of Walter Hall the wow factor is even more pronounced. I found myself unable to breathe at times, spellbound.

When that haunting bass line from the Eroica lifts its wounded head to peer out of the bunker where it has been hiding, it’s especially poignant that it be a single player. I thought Leopold changed Strauss’s piece, given that in the score we see that the bass plus both cello lines are all undertaking Beethoven’s melody. Maybe I’m wrong (as I was a bit dazzled and frazzled by what I was feeling and seeing and hearing) but I don’t think the first notes were played by three of the seven players before us, but only by one namely the double bass. Ha, maybe I’m wrong. I’ve now found and listened to a youtube performance of the septet version, and as I listen, I can’t tell for sure whether that’s a solo string bass or not (although it sounds so soft that I believe it’s just one rather than three). In theory I could have answered this question by the evidence of my eyes: except I didn’t realize what I was to look for until long after the moment had passed. Oh well. It’s still magic.

Having the piece in such a concentrated form was a powerful experience that I’m glad I was able to experience. Wow thank you TSM, for a fitting climax to a festival of “metamorphosis”.

The other two pieces on the program were notable for the comments by their perfectionist composers quoted in the program note, of wanting to transform, revise and change each work. Metamorphosis rears its head at every step of the process of composition, lurking in the back of the composer’s mind even after a work seems to be done.

We began with Poulenc’s Sextet, a mercurial work bursting with energy, sometimes taking tranquil breaks from its own relentless work ethic, before bursting forth again. The six were Stéphane Lemelin piano, Sarah Jeffrey oboe,Dakota Martin flute, Eric Abramovitz clarinet, Samuel Banks bassoon and Gabriel Radford horn. I resist clichés yet can’t fight the association of these instruments with comedy and entertainment, making the lightness of this frenetic composition an almost perfect balance with the gravitas we found moments later in Strauss’s elegiac piece.

The closing Brahms trio after intermission seemed perfectly designed to pick up the threads of what we’d heard thus far, sometimes playful, sometimes passionately emotive. The trio of pianist Michelle Cann violinist Andrew Wan and Desmond Hoebig cello took us on a heartfelt journey full of melody, thoughtful ensemble playing punctuated by bold statements from the piano.

I’m grateful that my last TSM concert of the season should offer such a thoughtful meditation on metamorphosis. Artistic Director Jonathan Crow seems to be taking the festival to greater heights with every season.