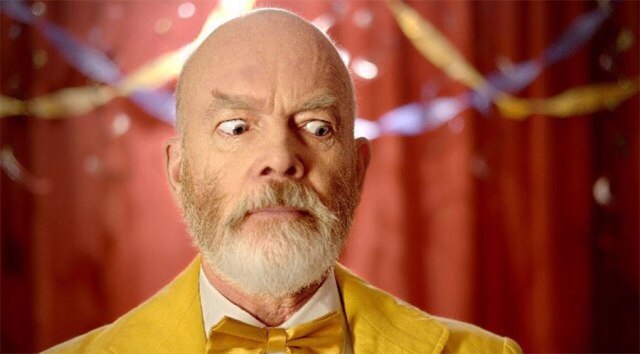

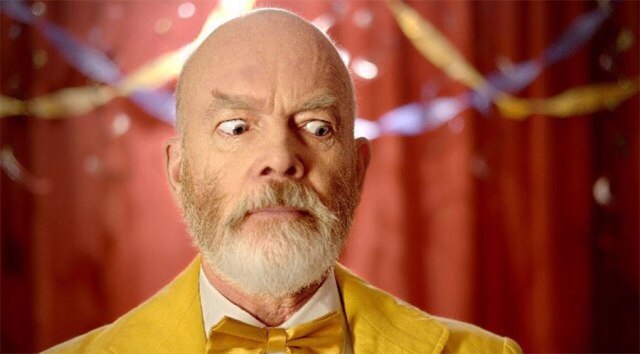

If you go to the theatre in Toronto it’s quite possible you’ve seen Thomas Gough. He has an avuncular presence, perhaps a result of years as a teacher, and so he’s perfect for roles such as Brabantio in Othello or Montague or Polonius. The voice is confident, the diction crystal-clear, and so it’s no wonder he does voice-over work. While he doesn’t look young I can’t quite tell how old he really is, because there’s a strength to his body language. So Gough is especially well-suited to playing a plum role such as Ebenezer Scrooge in The Three Ships Collective’s (with the support of Soup Can Theatre) upcoming immersive presentation of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol at Campbell House.

Actor Thomas Gough

I had to ask him some questions.

1 – Are you more like your father or your mother?

That’s not easy to say. I definitely have my father’s sense of humour, but I have large parts of my mother’s too. I am physically like the men of my mother’s family, except that I had my father’s reddish hair and lost it early, as he did. I have my father’s tendency to avoid things I don’t want to do, and my mother’s tendency to insist on getting them right when I finally start. My obsession with the English Language comes from both sides. My father was an excellent public speaker, and my mother did not like to be the centre of attention, and those things influenced me; there’s nothing I like better than making a speech to an audience of strangers, but I hate being the centre of attention when I’m off stage. (This latter characteristic is one I share with a lot of performers, which may surprise people outside the field.)

My father’s only sibling was a teacher, and my mother’s family is full of teachers and professors. I was a teacher for twenty-two years, and I found working with teenagers incredibly rewarding; that’s at least partly because I grew up in a family with a genius for loving its young. I can be happy alone for long stretches; in fact solitude is necessary to me, and that comes from both sides. I have four siblings, and my parents made sure that we all learnt to be content spending time alone, and they very deliberately hooked us all on the printed word; they both read to us when we were tiny, and they taught us all to read long before we ever went near a school. My mother refused to have a television in her house until her youngest child was an addicted reader, and to this day none of us ever stops talking except to read. I couldn’t begin to explain how important that addiction to the printed word has been in my life, or how profoundly grateful I am for it.

2 – What is the best thing or worst thing about being an actor?

The best thing about being THIS actor is being in performance. Memorizing lines can be an awful task; and rehearsing, if you do it right, is bloody hard work; but being on stage in front of an audience is pure terrifying joy. I grumble and curse and make a fool of myself in rehearsal and go home hot with shame about how obtuse and un-coöperative I must seem to the people who are trying to help me and I wish I could have some nice cozy job like defusing un-exploded bombs (which is at least not likely to trouble you very long); but then the moment comes when I actually get to tell the story to a living audience and everything is worth while and I wouldn’t give back a split second of the frustration or the repetitive pub meals (Do you have any idea how many actors die of scurvy? It’s a scandal, or it ought to be.) or the endless wandering around in circles trying to figure out which end is up or the never getting home for dinner or the friends who stop talking to you because you always seem to be in another world – if those things are the price of that wonderful evening when I get to tell the story.

The worst thing about being THIS actor is those bloody god-damned warm-up games many directors insist on. I hate them with a white-hot screaming passion.

3 – Who do you like to listen to or watch?

I couldn’t live a happy day without music. There are certain things that never fail to move me: Horowitz playing Scarlatti, Rubinstein playing Chopin, Heifetz playing Bach, Dinu Lipatti’s breath-taking “Alborada Del Gracioso”, Benny Goodman’s solo on “One O’Clock Jump” at the famous Carnegie Hall concert.

One of the things I love most about the Arts And Letters Club, which I’ve belonged to for nearly twenty years, is the fabulous lunch-time music programme, which has exposed me to so much music I’d never otherwise have heard. The club’s been essential in the development of my love for vocal music (speaking of the costs of being an actor: a few days ago I discovered that my next-day performance was a matinée, and not the evening show I’d thought it was, which meant I had to miss a lunch-time recital I’d been looking forward to for months, by a newly-launched young tenor named Jacob Abrahamse – if you love classical singers watch for him) and some music I’d never have expected to like. I remember a fantastic young pianist named Annie Zhou (watch for her too) who came a couple of years ago when she was fifteen and performed a wickedly difficult piece of Scriabin, and I just sat there thinking “Never mind the finger-work, how does a fifteen-year-old have the emotional maturity to do that?”

(Quick Canadian Fact: according to fellow-member Iain Scott, who knows these things, Canada produces more top-class operatic tenors than any other country. Somehow this surprises me.)

Actors? Among the famous, I think my favourite at the moment is Dame Judi Dench; I saw Rupert Everett in his show about Oscar Wilde a couple of years ago and he was wonderful. And I find it heartening that in Daniel Radcliffe a child star has for once made the transition to an adult career and has real talent and doesn’t seem to have been emotionally destroyed in the process.

But never mind the famous: there’s huge talent in the independent theatre in Toronto right now. Toronto is one of the very great theatre towns in the world and, with the greatest respect to the well-known established companies, it’s not entirely because of them. There’s fantastic stuff happening in holes in walls all over Toronto, performed by indie companies no one’s ever heard of because they can’t afford to advertise. It’s nice to be part of a close-knit community, but I get a bit sad whenever I go to an indie production and most of the people in the audience are actors, because they’re the only ones who know what amazing stuff their colleagues are doing. I really wish more people, instead of spending $120.00 to see The Sound Of Music again, would use the money to see five or six indie shows and have their brains scrubbed.

Indie theatre is ridiculously cheap and there are gems all over the city. Go and see Soup Can shows, or Safeword, or Single Thread, or Thought For Food, or Storefront, or Teatron Toronto Jewish Theatre – there are dozens I don’t even know; spend a few days seeing an indescribable variety of stories at the Toronto Fringe Festival every July. Of course you’ll see the occasional stinker, but you’ll do that in Shaftesbury Avenue or on Broadway, and for $10 or $12 per ticket what are you losing?

So, without wanting to be invidious, here are a few people I love to watch working, or to work with: Leah Holder, Kyle McDonald (worth it for that magnificent voice alone), Jakob Ehman (who’s going to Stratford next season), Kwaku Okyere, Conor Ling, Chloë Payne, the insanely talented Brandon Crone, Marie Gleason, Rob Candy, Jesse Nerenberg, Tyler Séguin, Helen Juvonen, Scott Garland, Alex Dault, Khadijah Roberts-Abdullah, John Fray, Kat Letwin, Benjamin Blais, Robert Notman, Tom Beattie, Joshua Browne – never mind, there are far too many and I could go on all night. If you’re seriously interested in Canadian theatre you need to know about these people and what they’re doing.

4 – What ability or skill do you wish you had, that you don’t have?

I’m helplessly addicted to music, but I have absolutely no musical talent, which annoys me. I also think it would have been fun to be a top-class song-and-dance man. But I try not to worry too much about the talents I don’t have, because that’s a great way to started neglecting the talents you do have.

And on this question of talent, kids: it’s not immodest to admit that you have it. If you never get to the point of looking your own talent in the face and saying “Yes, that’s mine, and it’s worth working and suffering for”, then how do you make any conscious and deliberate attempt to nurture it? Yes, of course, some people perceive in themselves talent which they don’t actually have, but I think a far larger problem is the numbers of people who unconsciously cripple themselves because they think that “Actually I’m pretty good at this” is something they must never say even to themselves. One of the reasons John Fray (if he will forgive me for singling him out) is so bloody good on stage is that he knows perfectly well that he has a lot of talent.

But instead of going around saying to random strangers “I am a very good actor; you may kiss my ring”, he says to himself “All right then, if I work like hell, this talent will allow me to turn in a clean tight performance that will actually mean something to those who see it.” I’m pretty sure that’s what all the good ones do. I know dozens of good actors, and I don’t know any who seem to be stuck on themselves. Their ego power goes into their work.

A pensive Thomas Gough portrayal. Did he see a ghost?

5 – When you’re just relaxing and not working what is your favourite thing to do?

I’m often working on more than one show. As I write this, I have a show closing tomorrow evening and a rehearsal for a second one on Sunday morning. And I’ve been cast in another big scary project which will start work as soon as the producers have raised the money they need to do it right. And of course my ball-of-fire agent Michael Rubinstein and I are always looking for auditions.

When I close a show and haven’t another to work on, I get depressed for a couple of days because I’m never going to see all those wonderful people in the same room again, and then I think “Yay, I can spend entire days reading!” And after a few days I’m starting to get restless because I want to be back at work.

Otherwise I read whatever looks interesting: I read a lot of history and biography, a lot of classic novels – I love Dickens, Eliot, Austen, Orwell, Forster, and I’ve read a few Russian novels in the past few years. Tyrone Savage lent me The Master And Margarita when we were working on a Canopy Theatre show together, and I loved it.

And War And Peace is not nearly as daunting as you might expect. I’ve never read a better or funnier book than Tom Jones. I have little or no use for Puritanism, but The Pilgrim’s Progress is a magical book. I love Patrick O’Brian’s twenty Aubrey-Maturin novels. I love the great humourists, both English and American: P.G. Wodehouse, Noël Coward, Saki, S.J. Perelman, Mark Twain. I wish I could read the great Jewish humourists who wrote in Yiddish. The only serious American novelist I know at all well is Sinclair Lewis, who is of course a satirist above everything else. For some reason I rarely seem to read anything by anyone who’s still alive, except history. I’m very sad to know that there will be no more books from John Julius Norwich, who died a few months ago. It’s actually scary and depressing how much I haven’t read.

But I console myself with the reflection that, as with music, knowing you’ll never have time to learn it all is preferable to being afraid that you’ll run out.

I listen to a great deal of music, especially piano music. I was exposed to the classics early and my father introduced me to jazz when I was at a very absorbent age. For some reason I’ve never been able to develop the smallest interest in the popular music of my own or any subsequent generation, which has always been a bit of a social handicap. I suppose my synaptic pathways were all constructed before I heard any popular music or something (says the award-winning neuro-scientist; I actually have no clue why it should be so.)

I love to eat lunch or dinner for hours at a time with one or two friends, but I can’t handle big groups. I love good restaurants and I am very nice to servers, partly because I have some understanding of how very difficult it is to do their work well; I love watching people do pretty much anything well. I hate loud noises and I can no longer pick one voice out of a noisy background. I find crowds exhausting and frightening. I love being alone, especially in a room full of books or in deep woods where there’s no one else but white-tailed deer.

More Questions concerning preparation to be Scrooge in the upcoming The Three Ships Collective’s (with the support of Soup Can Theatre) production of A Christmas Carol.

1 – What was your first experience of A Christmas Carol and how did it make you feel?

I was well into adulthood before I read A Christmas Carol. I had already read much of the rest of Dickens, and I think my first reaction to A Christmas Carol was that it wasn’t a patch on any of the great novels; obviously it wasn’t intended to be, but my first reaction was disappointment. (In passing, if anyone tells you that Bleak House is a boring book, spit in his eye; it’s a wonderful book.)

2 – One can imagine Ebenezer Scrooge done in a very theatrical style, larger than life and artificial, or much more realistic, and even intimate in his sentiments. Do you have thoughts on how you want to approach him?

Sarah Thorpe, our director, and I were talking about this a few days ago. It’s easy to see Scrooge as a one-dimensional character who suddenly becomes a completely different one-dimensional character. But that’s melodrama.

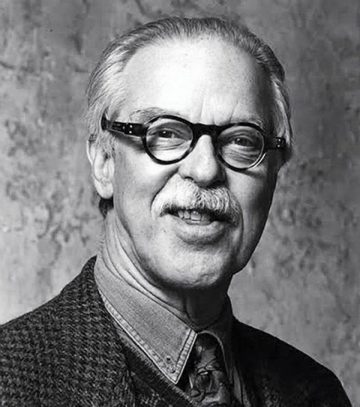

Justin Haigh, writer and producer

In Justin Haigh’s script there are several opportunities to show that though humanity and compassion are dormant in Scrooge, they’ve never been absent altogether.

Scrooge doesn’t become a different person; he wakes, slowly and painfully, from a long hard sleep. The Ghosts don’t put a spell on Scrooge; they help him find his way out of a swamp of loneliness and defensive ill temper he’s been so mired in that he’s forgotten there’s any other place to live. I hope we’ll be able to make audiences see him that way.

3 – How might an immersive version of Dickens change your interpretation?

I’m not sure how much it changes interpretation, but it definitely changes presentation.

Campbell House

I’ve worked in Campbell House before, and in Spadina House, and there’s an extraordinary feeling that one is hardly acting at all. It’s like being in your own house, talking at a normal volume, and there just happen to be a few guests there listening to the conversation. I find myself freed from any temptation to declaim, and I can achieve degrees of vocal subtlety that just aren’t possible when I have to project to the back of a 500-seat auditorium. In Campbell House the largest audience will be 28 people, and they’ll be close enough to touch the actors, though it’s generally appreciated if they don’t. I think that if we do it right, the illusion will seem less illusory than it would on a proscenium stage, which is, after all, a definitely artificial setting. In somebody’s drawing-room the audience is literally inside the fourth wall, hearing sounds and seeing gestures that seem to be presented exactly as they would in daily interaction with friends and colleagues.

I played Leonato in two productions of Much Ado About Nothing at Spadina House with Single Thread Theatre, and I remember going into the place for the first time and thinking “My God! What an ugly house!” mainly because it really is over-full of dreadful knick-knacks and much of the furniture was made in a period when everything was over-wrought. But by the time we got to performance I felt, every day as I entered the building, that I was coming home from the office and settling in for a cozy evening in my own house. I hope the audience felt the same way.

4 – In undertaking a part like Ebenezer Scrooge you’re stepping into a role like Hamlet or Romeo: where you and the audience will have seen many other versions. Do you have a favorite?

Director & Producer Sarah Thorpe

I’ve actually never seen any acted version of this story. I read the book about thirty years ago and I’ve heard people yack about it and I’ve seen the Scrooge character (and Tiny Tim, of course) exploited in advertising and so on. But really all I have to work with in this production is Justin Haigh’s script and Sarah Thorpe’s direction.

And that’s the way I like it. I did a production a few years ago with a director who was terrific in many ways, but he kept showing us clips of famous actors doing scenes from the play we were preparing. And I thought “Pops, you’ve never been an actor, have you? (He hadn’t.) You need to stop doing this. The LAST thing I want when I’m preparing a role is to have other actors’ interpretations getting in the way.” If I’m preparing Hamlet (unlikely at this point, and a role I have never had the smallest wish to play anyway), I don’t want to keep thinking about how Olivier did it, or that I’ll never match Gielgud’s performance, or wondering why some other actor made such a mess of some particular speech. And this is neither arrogance nor self-satisfaction.

Sorting out how to present a believable character on stage is quite complicated enough without have some unrealizable ideal (or some total hatchet-job, of course) haunting you the whole time.

That is the only thing that makes me glad to be so nearly illiterate. Of course I’ve seen, or read analyses of, a few famous performances (Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, Olivier’s Richard III, Mary Pickford’s King Lear, and so on), but not many. And I do my best to keep them out of my mind when I’m working. I want every text to be Urtext. I don’t mind seeing other performers’ interpretations after I’ve done something, so I can spend a pleasant afternoon thinking to myself “Granddad, why did you even bother pretending to play Cleopatra after Charles Bronson’s epoch-making production?” and then spend the next few weeks with my head in a paper bag so people won’t throw things at me in the public by-ways. But that’s after, not before.

You ask whose Scrooge moved me. Maybe mine; I don’t know yet. You ask whose Scrooge is to be avoided. Maybe mine; I don’t know yet.

5 – How do you relate to the arc of Ebenezer’s story, especially having to travel this pathway night after night?

Playing the same story night after night isn’t a problem; actors expect to do that. And no two performances are really the same, because every audience is different, and has its own effect on what happens. I think a lot of people who go to the theatre are unaware that the audience is an essential part of the performance; you can rehearse a show until you can’t possibly get it any better, and then the first time you get in front of an audience, everything changes.

You ask if the character of Scrooge at the beginning is a stretch. It is to some extent; it doesn’t come naturally to me to be deliberately unpleasant to someone who has done me no injury. On the other hand, I tend to be somewhat terse with fools and interlopers, so all I need to do is behave as if Cratchit is a fool (which Scrooge vaguely supposes him to be), and the collectors for charity are unwarrantably invading Scrooge’s space and wasting his time.

And Scrooge at the end of the play? He’s obviously a much more attractive person, much more the person one would choose to be. What will make him real and playable for me is the affection he conceives for Tim. There’s nothing more heart-melting than an unselfconsciously charming child, and it won’t be difficult to make Scrooge surrender to Tim. That affection is a redemption in itself.

How do I prepare? I’m afraid my approach is very dull: I sit in the quietest place I can find and think about what I’m doing. Physical warm-ups are a distracting waste of time and energy, and I have what my friend Jeremy Hutton calls an iron voice: it never gets tired and I never have trouble with it, so vocal warm-ups are superfluous. (I used to get bronchitis from time to time, sometimes quite badly. Once I actually had laryngitis, and it had no effect at all on my voice; I understand that this is a bit unusual.)

6 – Have you ever played a part like this?

No, not really. I don’t think I’ve ever played any character who did such a complete about-face. I really do like to have a new challenge with each role, and I think making that complete reversal of character believable is going to be the challenge here. There are a few sharp contrasts when I consider the show I’m just closing. In The Story Of Ethel And Julius Rosenberg (Teatron Toronto Jewish Theatre, Ari Weisberg) I played four characters, and because there was no time for elaborate costume-changes, I had to use four different voices (Neutral American or Middle Canadian newscaster, Louisiana, Manhattan, and vaguely German-Middle European) and variations of posture and movement to distinguish them. At one point I had to be three characters within about five minutes. In A Christmas Carol I’m one of few actors not playing more than one role, so all my changes of character must be internal, and I’m also going be muttering to myself “Ah, this is a scene with Mrs. Dilber…no, hang on, Alex is Mrs. Fezziwig this time. Damn, which scene is this anyway?” quite a lot until I’ve got much farther on with learning the text. And I have to learn the so-called “r.p.” accent, the standard more-or-less-upper-class English voice which for some reason, though my family background is about as fairly-well-educated- Anglo-Saxon as you can get, I have never been able to do properly.

So yes, there’s definitely some new stuff to do.

7 – What do you love about this story?

Well, call me simple-minded, but I love its happy ending. Scrooge is redeemed, Tim lives, and Bob Cratchit gets a huge promotion. I think we make a serious error in cramming the high-school curriculum with tragedy and despair. There are human stories – true stories – that end happily, and I think we ought to be teaching kids that they can have happy endings too. I think it was the grade ten English course we used to refer to as “the suicide course”; mercifully I never had to teach it. And while I flogged my older kids through King Lear and 1984 – books not only great and terrible but entirely human and believable – I also made them read Terence Rattigan’s The Winslow Boy, because not only is it a brilliantly constructed play, it’s a true story about a family that fights City Hall and wins. I don’t believe that terror and squalour and deceit and betrayal are all we have to look forward to, and I don’t think we should be teaching that they are.

I also love Dickens’s truculent liberalism. He draws the vulgarly opulent bank-towers looming over the streets teeming with half-starved labourers and crippled children, and he leaves no doubt at all about who he’s rooting for. He also shows us again and again something that remains shamefully true: that poor people are much more likely to be helped by poor people than by rich people. I’d like to think the occasional corporate bigwig who “can’t afford” to pay his employées a living wage might read this story – or much of the rest of Dickens – and be bloody well ashamed of himself.

And, as always, the extraordinary names, so utterly identifying characters in Dickens and nowhere else unless intended to evoke Dickens: Scrooge, Fezziwig, Crachit, Cheeryble, Pirrip, Twist, Rudge, Merdle, Gamp, Wittiterly, Squeers, Steerforth, Magwitch….

8 – Does the ubiquity of this story –constantly broadcast at Christmastime—make it harder or easier for you and the company?

I can’t speak reliably for the company. I don’t think it does either, though, for me. The people who come to see our show will presumably be those who are not sick of the story, to whom its familiarity is not a problem. By and large people come to see a play because they want to, and then of course we have them on our side before we start. And pretty much everyone wants to feel good about this story. They’ll want to enjoy what we’re doing and, on the assumption that we’re not simply atrocious, they’ll be happy to watch and listen.

And if we get a few people who are not sure they wouldn’t rather have stayed home to play cribbage, well, our job is to make them glad they came to see us instead. But that’s always our job. No matter how sure we are that the audience wants to be there, we still have to perform as if they needed to be persuaded. Half-hearted performance turns devotées into skeptics, and tells the skeptics that they were right all along. The other face of that is that we want them to like what we’re doing, so putting in our best work every time is very much in our own interest.

9 – Who other than Scrooge is your favourite character?

In this version of the story I can already tell I’m going to love Mrs. Dilber and the Ghost of Christmas Present, because the two actors (respectively Alex Dallas and Christopher Lucas) are already turning them into wonderful performance-pieces. And I suppose I love Tim, because I think Dickens, in the original, makes him a plucky kid we want to pull for but who is not repellently noble about his illness. Dickens’s sentimentality can be a bit trying, but I think he manages to avoid it with Tim, and we get a true picture of a kid playing a tough hand without moaning on about how unfair it all is. I suppose I find Tim’s sweetness convincing because in my mercifully limited experience of seriouslly ill children that’s how they really tend to be.

10 – If you could play any Dickens character, who would you want to portray?

That’s like asking “What’s you favourite book?”! How could you possibly choose? Dickens draws characters better than anyone, and every imaginable human being appears somewhere in Dickens. So I’d love to play Mr. Micawber, or Sairey Gamp, or Wackford Squeers, or the Cheeryble Brothers, or Fagin, or the deliciously appalling Harold Skimpole. There are dozens an actor could feast on.

11 – Is there a teacher, actor, director or an influence that you especially admire?

Dozens, but three to whom I am especially grateful, and without whom I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing:

a) My favourite Shakespeare director, Jeremy Hutton. It was through acting in several shows directed by Jeremy at the Hart House Theatre that I began to believe I might have talent, which I had never understood before,

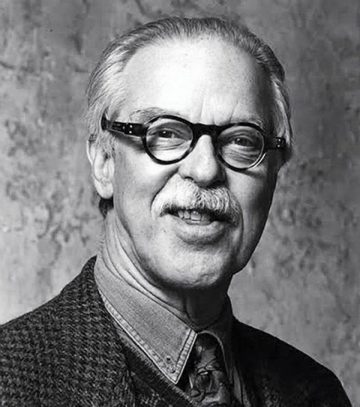

Martin Hunter

b) My late friend Martin Hunter, who talked me into believing that I was good enough to be taken seriously as a professional, and

c) My very dear friend, the producer, director, and miraculous photographer John Gundy, who made me understand that since I had talent, I really needed to use it.

And, if you will allow me, I’m going to answer a question you haven’t asked:

12. Do you think people will really enjoy the Thomas Gough production of A Christmas Carol ?

No, because there is no such thing. This is a collaborative effort. Theatre is always a collaborative effort (not collective, which is quite different. Collectivity is possible, if you like that sort of thing, but collaboration is essential.) We have fifteen actors and a production team, so far, of seven. I’ve worked with some of them before and I know what spectacular talent we have on board; and I’m seeing more of it every day in cast-mates and crew members I’ve never worked with before but am very glad to be working with now. The smallest roles, the briefest scenes, are all going to be as important to the total impact as Scrooge.

And I strongly suspect that people outside the theatre tend not to be aware of how much support actors need to do what we do. You never see the designers when you go to a play, but you are inescapably affected by their work. Adapting another writer’s work and shifting it to a different medium; finding appropriate costumes, after you’ve done days or weeks of research so you know what to look for; listening to a library of music to choose exactly the right things, which you then have to transpose and arrange; teaching the cast to speak in an accent that is unnatural to them; imagining how you can achieve romantic or menacing lighting effects with very little flexibility in your equipment; thinking through every possible nuance of a complex story so you can direct a group of people who all learn in different ways, answering unexpected questions on the fly and conducting agonizingly detailed conversations about aspects of the play that some demented actor just started worrying about five minutes ago; welcoming all these strange people into your space, which is not usually used this way, and making accommodation for their endless special requirements: these things are all complex, difficult, and absolutely essential, and the people you see on stage didn’t do any of them. Is somebody going to be barefoot on stage? Then we need an absolutely reliable stage-hand to sweep the playing surface so actors don’t wind up with random bits of metal in their feet. Who’s going to do the actors’ laundry? We can’t let them take it home because they won’t all remember to bring it back. You need a thoroughly competent and conscientious producer to make sure all these things happen. And finally you need a stage manager, who must be a diplomat, a conciliator, a disciplinarian, an articulate communicator, an instantaneous problem-solver (I complained about being cold at rehearsal yesterday and bang! Kathleen Hemsworth draped a blanket over my shoulders; I have no idea where she got it – produced it from thin air for all I know), a den-mother, and a miraculously talented organizer.

Nothing good ever happens on stage without a good stage manager. Yes, all those people are working with the ultimate goal of getting actors in front of an audience looking and sounding as good as possible, but actors are the tip of the iceberg. Without all these others, actors would be absolutely helpless; there would be no theatre. So I hope the people who enjoy our production of A Christmas Carol will spare an appreciative thought or two for the technical wizards who have made it happen.

*******

The Three Ships Collective’s (with the support of Soup Can Theatre) present their immersive production of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol at Campbell House Museum December 12-22. For further information see Christmascarolto.com