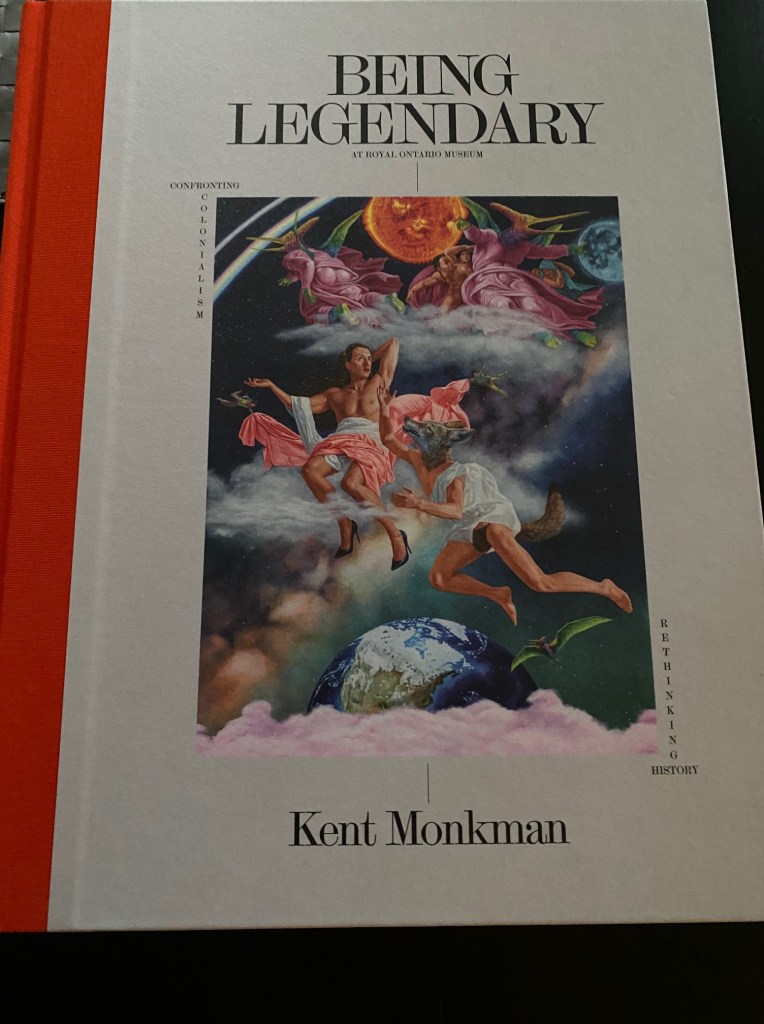

Kent Monkman’s current show Being Legendary at the Royal Ontario Museum continues for a couple of weeks more until April 16th. Art Canada Institute have created a book that helps preserve the show and its impact.

I’ve been pondering the combination of displays, words in three languages (Cree, English and French), artifacts and art in the installation. One can understand it as much from what it is not as from what it is.

The ROM installation performs some of the same sort of reframing seen in the two big paintings at the Metropolitan Museum, that reference art in their collection. Similarly this is a chance to address images of the world as seen in the ROM. It’s not just art and the representation of Indigeneity, as at the Met.

Our focus shifts this time from the preoccupations we’ve witnessed before in his work. The art Monkman presented in his Shames and Resilience show that came to the UC Art Centre in 2017 as part of a national tour was galvanizing in showing us the experience of Residential Schools, especially The Scream (2017), while raising the question of Indigenous representation. The show includes a 2016 painting Death of The Virgin (After Caravaggio) , that reframes the original composition, as though to begin to address his concern, as he stated in the Foreword to the show’s brochure:

“I could not think of any history paintings that conveyed or authorized Indigenous experience into the canon of art history. Where were the paintings from the nineteenth century that recounted, with passion and empathy, the dispossession, starvation, incarceration and genocide of Indigenous people here on Turtle Island?”

That ironic reframing of old images, that was so prominent in the two massive works at the Metropolitan Museum in NY from 2019 to 2021, takes a new form this time at the ROM. We’re not to worry so much about art history and the representation of the Indigenous experience in art as we’re to focus on colonialism and history. The ROM’s collection takes a role similar to the one taken by the Met Museum. Where the art in NY that could arguably be called “the canon” by being the collection in the biggest museum in the greatest city in the western world, furnishing the context for Monkman’s reframing, the ROM’s collection stands in for the broader world of nature, the dinosaurs and the natural world in which we live, a snapshot of western cultural assumptions that go with histories as part of the colonizer project that Monkman interrogates.

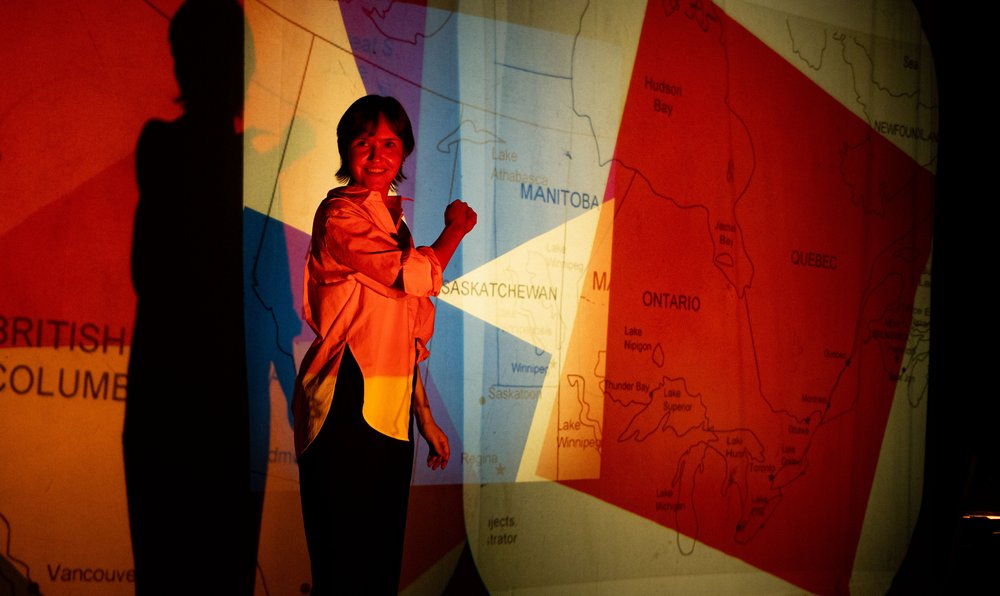

While I’ve had powerful responses to the artist before (especially recalling the way I was impacted by his 2017 show) I did not expect the experience I had at the ROM. I’m not an art critic, nor am I Indigenous, so I think that qualifies me as a typical Canadian. Full disclosure: this is a description of my emotional experience at the ROM instillation, struggling with what I saw & experienced.

I felt that he softened us up with the first part of the show before delivering a gut-punch in the second half of the show, eliciting more tears than I’ve ever shed for art in a gallery. I experienced Monkman’s work in a kind of dramatic tableau, a sequence of scenes curated for us, and recall Monkman at this moment as an artist who was worked in film and theatre, not just the art gallery. Indeed I’d like to see him make something for the theatre. Here we begin with something light & positive, a joyous series of images featuring spirituality alongside science, without the kind of disciplinary divisions we normally crash into in museums or universities. A world with stars and rocks, little people and dinosaurs, Miss Chief’s high heels and handmade moccasins coexist happily: because at least for the moment his art and the installation present a vision of the world before the fall (if you can forgive me for inserting a peculiarly Christian metaphor, apt for the time of year), aka before the settler invasion. And this merging of spirit and science and culture are refreshingly free of the sort of second-guessing by the positivistic scientists insisting on the primacy of that which can be proven and known with photographic proof. Myth and science co-exist for the moment in this first part of the installation.

Then things turn abruptly: as they did in history as we arrive at what felt like the climax of the show, the drama of the room with three powerful paintings of children. This segment of the show (and the book) has the title “When they tried to break our spirit”.

The first is in a darker recess of the room, immediately suggesting its importance. I believe the picture is titled “The Sparrow”, although the book reproduces “A study for The Sparrow”, possibly because the painting was not yet finished. A child reaches towards a sparrow just out of reach in a residential school room, that I almost think of as a prison cell, what with its windows covered in bars, the rows of beds and the crucifix on the wall. I’m conflicted speaking of that cross –especially at this time of year—when of course that image reads different to someone embracing a religion without any awareness of the oppressiveness with which these children were treated.

Jesus himself must blush at the thought.

We see a child hiding from pursuit by a distant Mountie, shushing the little people who watch from among the flowers. The painting is titled “The Escape”.

And the one that really got to me is the picture where we see children, as viewed from the point of view of the ones being executed in the 1885 conflict.

The signage identifies the painting as “Compositional study for The Going Away Song”, although in French it says “Le chant etc” so perhaps the painting is “Going Away Song”. I don’t know for sure.

I didn’t understand this at first, only that I was crying and upset. Later I figured it out. The viewpoint of this painting looks out between armed Mounties from underneath a scaffold as where one might end up when executed by hanging. I was also very moved by the text in the signage, in three languages.

I found it impossible to continue happily going through the installation when I’d seen this painting, looking at the group of boys in the centre of the painting, and retreating out of the room to gather myself together. Once again (recalling The Scoop or The Scream) Monkman shows us the impact upon the children.

I’ve included a photo I made of a detail of this painting, from the book, to try to show you some of the power of Monkman’s painting. I put it sideways because I wanted to make something a little bit as monumental as what he’s made.

At the ROM show, I came back briefly to look around, but I was still too upset to really digest anything. I only really took in the rest of the installation through the retrospective views offered by the book. I did look at the moccasins in the next part of the installation, silent testimonials to heroes and I realized later, a disturbing echo of the museum specimens, of lives lived.

Being legendary indeed.

There’s more to the show but for me this was the part that reverberated with me over the next days, as I couldn’t get the images out of my head.

I’ve looked through the book several times since going to the ROM during March Break. Being Legendary at the Royal Ontario Museum continues for a couple of weeks more until April 16th.

To obtain books on Monkman as well as recommended reading from the ROM Boutique click here.