There are at least two ways to understand music.

We listen. Perhaps you hear a performance on some device such as your smartphone, your TV or a computer, or even in a live setting such as a concert or a church. It may be something from the past, for instance when we’re talking about someone like Ludwig van Beethoven in anticipation of his 250th birthday. It could be a popular composer such as Taylor Swift, John Legend or a film-music legend such as Ennio Morricone. But in each case the encounter with the music itself is through your ears. I don’t deny that other senses come into play, that there’s a visual component too, particularly if you’re watching Swift or looking at how Morricone’s music works in a film.

But there’s another way many of us encounter music, and it’s usually how one learns music, when we’re taught how to sing or play an instrument, perhaps how to read music or charts.

And so in addition to listening to music we may sometimes make music: or at least that is the goal.

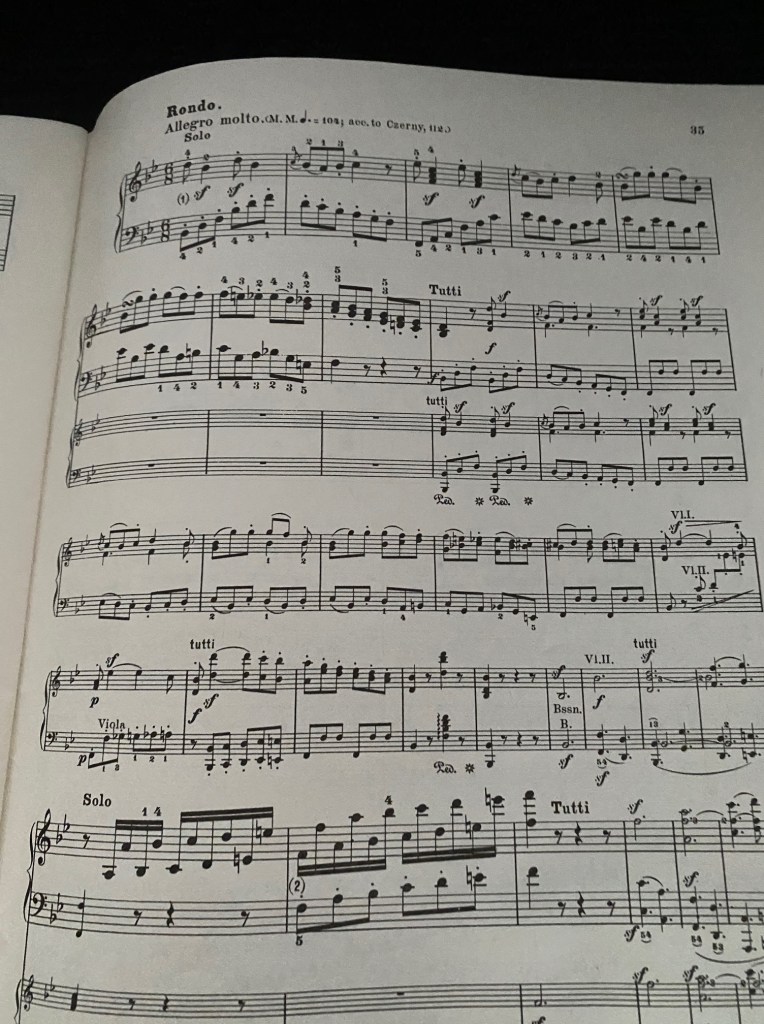

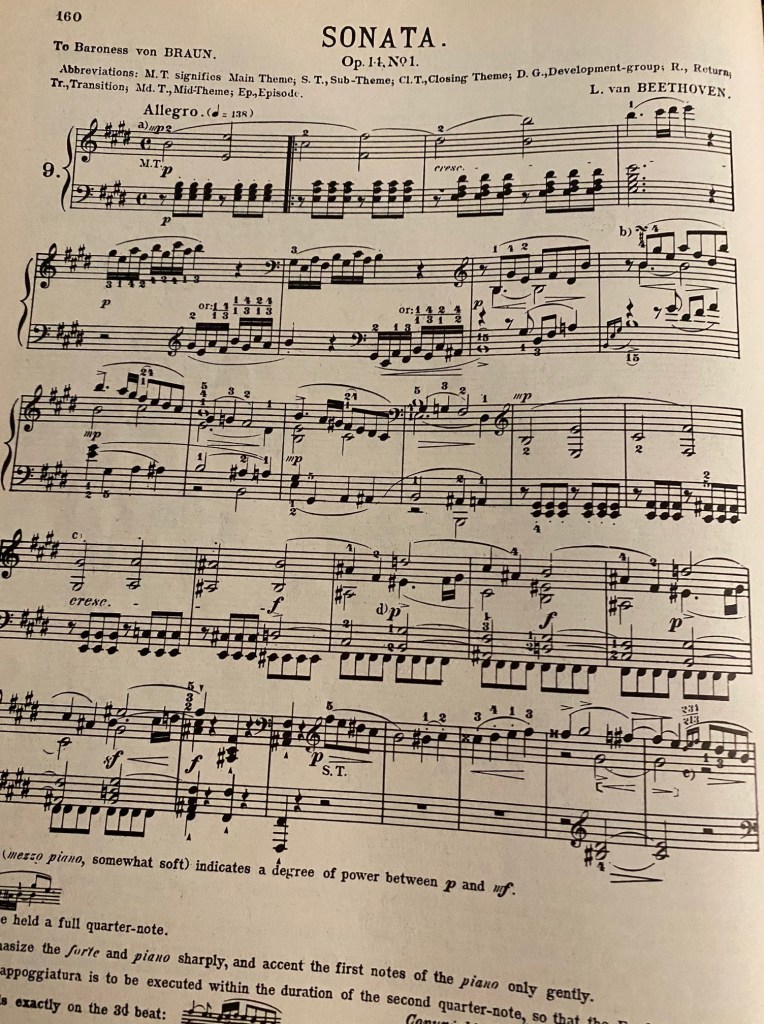

This is the first Beethoven Sonata I studied. I was much younger, under the guidance of my second teacher, Harold Patterson (I hope I spelled that right…) at the Royal Conservatory of Music, North Toronto Branch, on Yonge St, roughly 15 minutes walking distance from my childhood home.

I wasn’t afraid of it or intimidated, although Mr Patterson always said “Beethoven” with a curious emphasis, not unlike the way some people will say the names of Biblical figures such as “Pontius Pilate” or “John the Baptist”. I was to understand that this was an undertaking, that I was privileged to play this music and must treat this as a significant challenge.

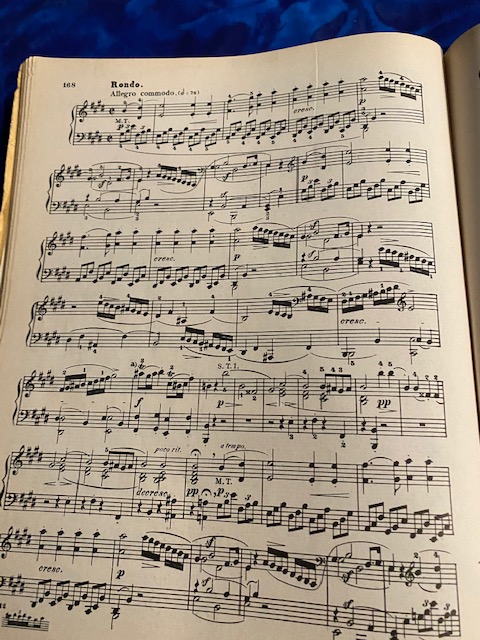

The first time I looked I noticed something in this piece that has best been captured by something I read decades later, from Claude Debussy, who spoke of baroque composers such as JS Bach. Debussy observed that the notes on the page were like the patterns of arabesque, a word with mysterious connotations that I’m sure the French composer likely encouraged. Whatever else is going on, the music is beautiful to look at on the printed page.

That page of music is the site for an encounter between the player & the composition, as though it were a football player meeting the football. Does that sound crude? It’s easy to make noise, harder to make something beautiful. But we can imagine a vast continuum of ability between those (at any age) who are just beginning to play, and those who have acquired expertise, mastery, even virtuosity. The music may require care from the player, perhaps playing it slowly, perhaps only undertaking a few notes from one hand or the other rather than taking on the whole piece. If one has heard the piece before, if one is a good sight-reader, one might dare to play the whole thing up to speed. Sometimes we have no choice, as that’s what’s required in a church or music-theatre or opera when someone puts a score in front of you and you have to make it happen with little or no opportunity to practice.

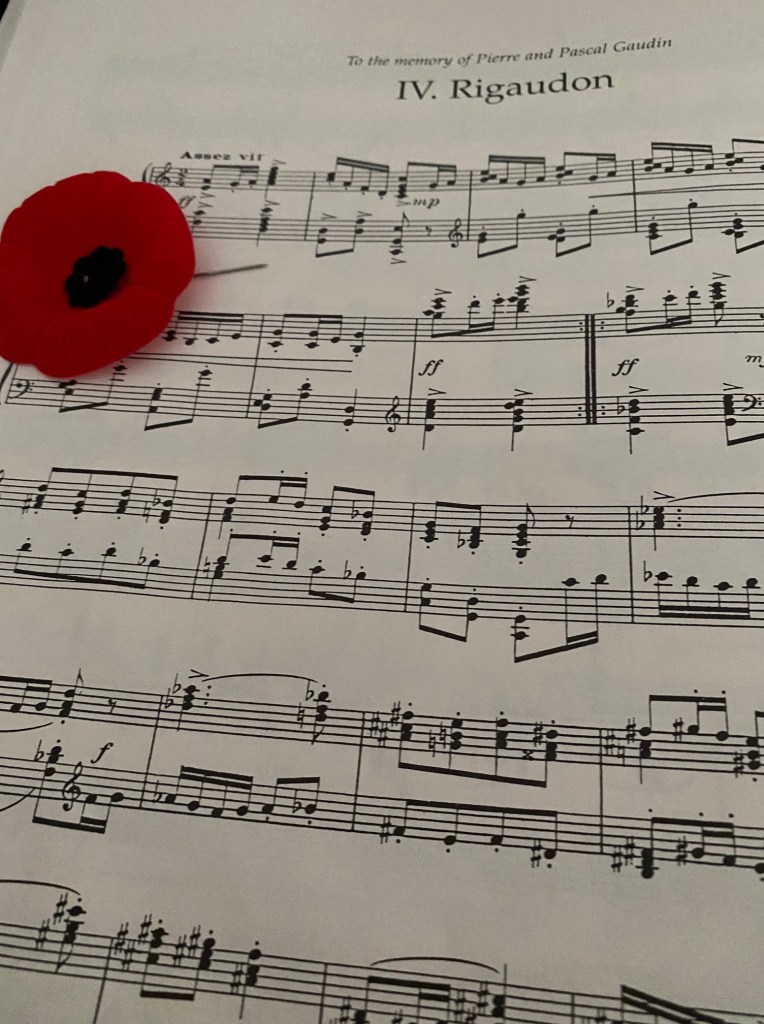

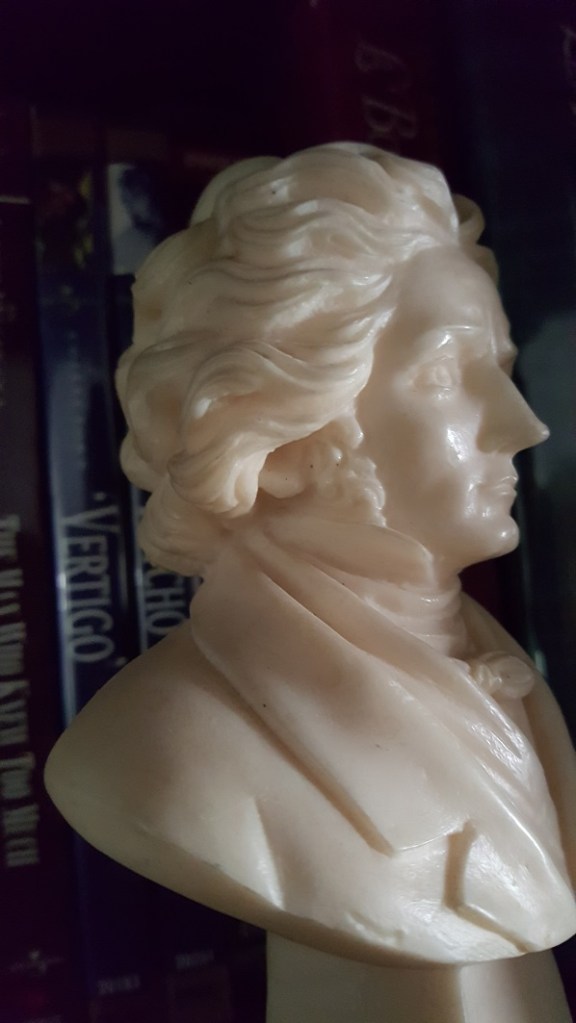

Beethoven himself was recognized in his youth as a great player, a virtuoso artist: even as he concealed the secret of his growing deafness. In the modern era we may look back upon people who were known as composers or pianists, applying a label that may not be how they thought of themselves, persons without any awareness of being only one or the other, not both. Mozart played the fortepiano, (which isn’t the same as a modern pianoforte) and also played the violin, writing music for both, also operas & masses and many other types of music. Besides the many things he would accomplish, Beethoven was a great pianist who wrote great music for the piano. In the next century music was often designed to challenge the player, displaying their virtuosity. Think of Beethoven in the lineage that leads us on to Chopin & Liszt, Mendelssohn & Schumann, later Ravel, Rachmaninoff, Busoni, Bartok, Ligeti…

For me it’s the inevitable subtext when I’m listening to Stewart Goodyear or Yuja Wang playing a piece. The virtuoso might be understood to be on a spiritual quest, where the great compositions are like the mountains to be climbed or oceans to be crossed: with nothing more than their fingers to take them and us on that journey of exploration. It can be one of the great joys to encounter a new approach, although for some listeners this is heresy: that one might dare play something in a new way. There is a discourse around performance of a particular work, where we understand the conversation between the way it has been done and the possibilities to do it in a new way. I listen, intrigued, because I’m a fellow traveler on that quest, admittedly never likely to venture as high or as far. But the Olympic motto “ Citius – Altius – Fortius” (or in other words “Faster – Higher – Stronger”) is not irrelevant. Singing or playing an instrument does entail the expenditure of energy, making the athletic analogy at least something to consider. If you consider the athleticism of dance –the necessity to train and strengthen while retaining flexibility & agility—remember that the fingers are doing something like a dance on the keyboard. Some pieces are very quick, sometimes calling for a big sound, sometimes for something gentle. A player’s strength & agility are indispensable to the fullest expression of what’s on the page. Some pieces are exhausting. Some pieces require great delicacy.

Although Beethoven died in 1827 we are far from having exhausted the possibilities in his works. As with the plays of Shakespeare or the operas of Wagner, there are still interpretive pathways available to make something new of something old. I recall my excitement in 2012 when I heard that Canadian pianist Stewart Goodyear was undertaking something called the “Beethoven Marathon”, playing all 32 sonatas in one grueling day, concerts in the morning afternoon & evening. As a mental achievement alone it’s remarkable, a bigger feat for instance than the roles of Hamlet or King Lear, each a few hours shared with a cast, where Goodyear played alone through all 32 sonatas.

I was inspired by the film Julie and Julia, following the parallel stories of Julia Child virtuoso chef and Julie Powell, emulating her and writing about it on a blog.

So I tried approaching Beethoven in a new way. Never mind the challenges of playing this sonata or that sonata. What if one played them all, one after another? I couldn’t help noticing resemblances, when one is hearing the sonatas in one’s head, played one after another. The concluding chords to Op 101 almost sound like a taunt inviting the opening of Op 106. (try playing one after the other). One sees patterns. And so as I thought about Beethoven & Goodyear back in 2012, I wrote a few times about it, not unlike Julie contemplating French cuisine & Julia.

Let’s come back to piano sonata #9, a piece I started to learn as a child. Was I 13? I’m not sure but when I look at what a mature artist does with the music I’m humbled to think that I was unafraid to play this music. With maturity comes fear I suppose.

I really like Daniel Barenboim’s reading of Sonata #9. He had a program that I saw on TVO long ago called Barenboim on Beethoven, a wonderful combination of remarks & performances.

Barenboim’s version is not as quick as Glenn Gould’s performance, one that might remind you of that Olympic motto Citius – Altius – Fortius.

To each their own. I prefer the way Barenboim lets the music breathe, giving space for reflection. The two readings are so different from one another, bringing out different aspects of the same music.

Isn’t it amazing.