|

|

|

|

Welcome to the Club!

Please join us at PAL’s Crest Theatre Green Room on Thursday October 24 for a star-studded evening in support of the programming at PAL’s Celebrity Club!

110 The Esplanade, Toronto

Featuring:

Sean Cullen

David Warrack

Theresa Tova

Micah Barnes

Laura Hubert

Melissa Story

Peter Anthony

Donne Roberts & Yukiko Tsutsui

Ori Dagan

Tickets: General Admission $25 / PAL Residents $20

Click for info / advance tickets

Tonight I was present at the Canadian premiere of Yang Zhen’s third installment of his “Revolution Game Trilogy”, Minorities, a Red Virgo production presented by Canadian Stage.

You will recognize many things in this show.

We watch five female dancers later joined by a singer. We begin with the stillness of a minimalist tableau that reminded me of Robert Wilson’s Turandot, until the cartoon faces unexpectedly start singing, including a comical Mao Zedong. The energy is wildly happy, with the subtlest overtones of disrespect.

Minorities, with a smiling Chairman Mao peering over their shoulders (photo: Dahlia Katz)

And then each one presents herself as a member of an ethnic group associated with a place.

Macao: Lou Hio Mei

Uyghur: Guzhanuer Yusufu,

Mongolia: Aodonggaowa

Tibet: Gan Luyangzi

Chinese Korean: Ma Xiao Ling (I did not know that there were Chinese Koreans)

At times we heard them speaking their language, at least I think so because of the variety we heard. These are very beautiful to hear, whether or not they are also mixed with a few English words. When have I ever heard so many languages in one short evening’s program?

They were dancing their national dance, attired in their folk costume, sometimes singing or playing music. For awhile it moves along very conservatively, each one showing us something about themselves, teaching us about their past even as we get glimpses of complexities & conflicts.

We’re told of the pressure to conform & to blend into the bigger cultures while abandoning one’s authentic language. I’m reminded of the cultural genocide here with the Indigenous populations.

At one point the safe and conservative music is juxtaposed against something wildly provocative, in costuming that’s modern. I won’t say much because I don’t want to spoil the effect, other than to say that they are on the edge of a kind of satire, where lip service is paid to the Cultural Revolution & Madame Mao even as those values are mocked & parodied.

It’s among the subtlest satire I’ve ever seen, from a group of performers who were always positive, smiling & welcoming to the audience.

I had a wonderful experience. Before the show began the young woman sitting next to me said a quiet hello, which I wasn’t sure whether it was directed at me or the person beside me. I think perhaps it was meant for both of us? We both quietly said ‘hi’ back.

A couple of minutes later she said hello again and this time it felt more like it was for me, and so I answered. We began to chat.

I was fortunate to be sitting beside Ma Xiao Ling, who pointed to her picture in the program and said “that’s me” in a very friendly voice.

And so we chatted. I asked her how many languages she speaks (a few… including a fair grasp of English), asked her about her discipline (she’s a dancer, she started at the age of 7 and has been dancing for 20 years… so I concluded she must be 27), and the future of the show (after 10 days here they’re off to San Francisco). After she had told me who she was (pointing at the program) it only seemed fair that I should give her my business card with the blog’s address although I don’t know if she will see this review.

And when the loud music began, she and a few others seated in the audience got up and began to dance ever more vigorously in place before going to the stage. At times it’s the folk dance that conforms to the values of the Cultural Revolution, at other times much more modern & radical.

If you go see this show and one of them addresses you I recommend that you talk to them. You won’t regret it. It’s truly immersive, as we they sometimes came right into the audience to interact with us, and then taking some of us onto the stage to dance later on.

More and more I think that a discipline can be like a fortress that offers a place for people to hide. Canadian Stage have become a company curating experiences that mix disciplines while challenging our expectations, and avoiding the safe & easy pathway. We’re in the presence of music, dance, layers of meaning in the words & images, animation & text.

I didn’t know what to expect when I came in, and indeed am a bit mystified by the cool surface of Minorities. There’s a sentence in the program that I have come back to more than once, as I seek to unpack the layers of irony:

“Yang explores the constant conflict between social prejudice and individual consciousness—how one can express oneself and relate to the world in which they live—and examines how minority identities in China fit, or don’t fit, in the narrative of a harmonious One China.”

At times we’re hearing of the 56 different ethnicities, reconciled into the One China especially in big loud songs that sound like communist propaganda. The dancing is enthusiastic, even if we’re given images to problematize their ideal utopia.

Minorities is a piece of dance theatre to challenge preconceptions & assumptions even while offering you something that feels very sweet & kind, continuing until October 27th at the Marilyn and Charles Baillie Theatre aka the Berkeley St Theatre.

Tonight the Canadian Opera Company premiered their take on the recent Lyric Opera of Chicago production of Dvořák’s Rusalka directed by Sir David McVicar.

It stands in rather stark contrast to the other current COC production, Puccini’s Turandot¸ whose mise-en-scene seems at odds with the score. Richard Wagner would recognize McVicar’s reading of the story as “Gesamtkunstwerk”, his ideal of the total art work where all the components work together to tell us the story. While it may be that both Puccini & Dvořák would have wanted a unity between all interpretive elements, McVicar’s approach is recognizable in the usual sense as a production honouring the work. Yes it’s still the story of a mermaid who becomes mortal because of her love for a prince. While it’s a bit edgy and up to date in its portrayal of nature and humankind’s relationship to the environment, the conservative audience would take it to its bosom –especially after Wilson’s minimalist stylings—for its willingness to follow the score.

Ballet makes a welcome return to the Four Seasons Centre stage even though holy cow it’s not December / Nutcracker season. Yes Virginia, they do sometimes put ballet into opera. In fact many were written that way, although you’d never know it from COC productions such as the Aida they’re reviving later this season. Andrew George’s choreography brings the work extra dimensions, sometimes symbolic sometimes a wacky diversion. The energy dance brings to the work helps propel the story during a rather long evening.

Whatever else one might say about this show, it belongs to Sondra Radvanovsky, who sounds better this year than ever. While the opera is sometimes a little melodramatic and not to be mistaken for Shakespeare, Sondra’s toolkit matches the work perfectly. There’s a different movement vocabulary for each act, creating a different tone. There’s a long stretch where the character is silent, unable to make a sound as a condition of becoming human; Sondra does these scenes as well as I’ve ever seen them done, with some brilliant moments incorporating the ballet. In the last act she reminded me of a wounded animal, heart-breaking…

(centre) Sondra Radvanovsky as Rusalka (photo: Chris Hutcheson)

Anthony Tommasini’s book The Indispensable Composers does not include Antonin Dvořák in its list of the most important composers: and perhaps it should. Rusalka is one of the most beautiful opera scores. Tonight we heard stunning work from the COC Orchestra led by Johannes Debus in an idiomatic reading. At times we might mistake Dvořák for his near contemporary Brahms, who did make Tommasini’s list even though he is not Dvořák’s equal (in my opinion if not Tommasini’s). Sometimes Dvořák descends into a splendidly ethnic sound for instance in the opening to Act II, a delicious scene with a decidedly Czech flavour. Debus keeps things moving, while the orchestra let their hair down, sounding properly Slavic.

This is one of the strongest recent COC casts. Alongside Sondra, Pavel Cernoch’s Prince is more than a pretty face, especially moving in the last scene. It’s a bit of a miracle that he can be so sympathetic in this role (the Prince being one of the least sympathetic characters in all opera). I was surprised by a flood of tears in the last scene: although Sondra deserves some credit for the impact of the final moments. And Keri Alkema is again a dramatic standout giving the Foreign Princess a somewhat feminist edge in her scenes with the Prince, while sounding terrific as well.

Stefan Kocan’s Vodnik was vocally tremendous, but again benefits from a production that lends gravitas to his every word as a kind of voice for Nature. Elena Manistina seemed to be having a great time as Jezibaba, injecting real star power both with her solid sound & her readiness to camp it up. Every time she showed herself it felt like a party was going to break out, and come to think of it, that’s more or less what happened. Matthew Cairns & Lauren Eberwein took over the show whenever they were onstage, playing up the comedy in their roles as the Gamekeeper & the Turnspit, and sounding terrific.

(sitting centre) Lauren Eberwein as the Turnspit and Matthew Cairns as the Gamekeeper (photo: Michael Cooper)

I’m seeing the show again, and would suggest you do so too. Rusalka continues at the Four Seasons Centre until October 26th.

The title tells the story.

Night #2 in the Amplified Opera opening concert series at the Ernest Balmer Studio was The Queen in Me, a performance piece straddling the line between surreal confessional and stand-up comedy, a brilliant piece of satire for a specialized audience.

The Queen is that badass character in The Magic Flute, the Queen of the Night, soldiering against one of the most misogynistic storylines going. Sometimes the Queen sings what’s written and sometimes she bursts out of the strait-jacket of the character, both in the mechanical sense of her costume and the subtler implications of the role written for her. She is a perfect mechanism for the exploration of the mad world of opera, the many females co-opted into rituals celebrating female subjugation: except the Queen won’t do it anymore. She seems to be on a quest, exploring different roles as ways to articulate the feminist position, sometimes working within a role, sometimes fighting or subverting it. I can recall previous satirical pieces in different decades that were knowing nods to the audience, while more or less keeping the artform & its creators (this time Mozart & Schikaneder) on their pedestals. This time it’s more in keeping with the mission of Amplified Opera, as a site for activism and shit-disturbing, largely in fun yet with an underlying seriousness to its mission. They appear to be fearless.

Do you mind a few words about astrology?

Amplified Opera was born yesterday, October 10th. That birthday in some ways couldn’t be more perfect for this new company. 10-10, in the astrological sign Libra, the scales, which signifies balance, the symbol of judgment & justice. Yesterday we saw Aria Umezawa direct a piece with some wit & humor but mostly seriousness, followed by an intense talk-back session.

Teiya Kasahara

Tonight it was the turn of Aria’s artistic partner Teiya Kasahara, a tour-de-force requiring brilliant singing, acting in multiple languages & several layers of irony. As I look at the two nights (and muse upon Saturday night’s program which I must miss) there is certainly a kind of balance at work between the two. It feels very much like yin & yang, the complementary sides of the operatic coin of dramaturgy and virtuosity, the director and the singer. The perfection of the symmetry whether in that 10-10 or in the balance between their personas or even their names is boggling my mind. My jaw drops as I think of what lies ahead for this intriguing company and its brilliant collaborators.

Afterwards we had another wonderful talk-back session, contemplating such things as the limits in the current operatic industry, proposing ways to break through to something new & wonderful. Watching Teiya sing parts of roles that one wouldn’t expect (thinking of the “fach” system, which categorizes the vocal requirements, and Teiya’s remarkable voice that transcends the usual limits), we went on to discuss the ways that pedagogy & the industry condition a culture resistant to change & newness. It’s breath-taking to imagine what the industry might become, especially through the injection of this new company’s creativity & politics of inclusivity.

Trevor Chartrand was a supportive presence at the piano, sometimes playing the piano part of the arias Teiya was exploring, sometimes taking us to wholly other realms –for instance in a soft & seductive reading of the Dance of the Seven Veils—in perfect partnership with Teiya. The piece was developed with Director Andrea Donaldson, a work in progress that I understand is coming back. If and when that happens don’t miss it, both for the amazing musical performances and the quirky satire.

The third night of the series (Saturday: October 12, 2019 @ 7:30 – What’s Known to Me is Endless at the Ernest Balmer Studio) concludes this brilliant launch of AMPLIFIED OPERA.

I offer Teiya & Aria my congratulations for an auspicious beginning.

Ernest Balmer Studio, 9 Trinity Street Tickets:

$25 at door, or online at http://www.amplifiedopera.com

More information: http://www.amplifiedopera.com

Both works currently playing at the Canadian Opera Company feature a famous aria known by people who might otherwise not know the whole work.

In Turandot it’s “nessun dorma”, a piece associated with Luciano Pavarotti, and maybe a little bit with Aretha Franklin.

Perhaps they’re discussing it in the afterlife, …somewhere …. Up there?

Excuse me I can’t help thinking that way, because of the other opera and its big number.

The “Song to the moon” from Dvořák’s Rusalka is heard in recitals and on the radio, while the full opera, not so much. If you know the aria you may already know why I put that funny headline on this little meditation.

Suppose I play you a famous tune by Harold Arlen, that is closely associated with Judy Garland and the film The Wizard of Oz.

That opening phrase of the song, an octave leap upwards, seems to capture a wistful hope for a new life in a new place.

Arlen might have heard something like this before. Did he know Rusalka? I have no idea. But listen to the “Song to the moon” and judge for yourself.

And fortunately the soprano in this little clip happens to be the same one we’re hearing in Toronto namely Sondra Radvanovsky.

Which one do you like better? (i like both)

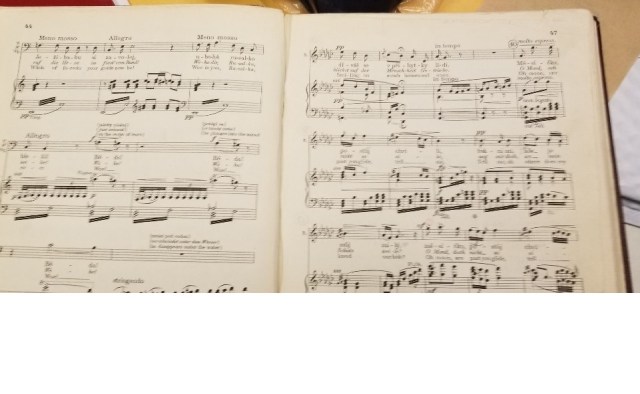

Today I went to the library to get a copy of the score.

I was cautioned as I took that particular score out. There are 3 in the collection:

I was cautioned! A page was missing.

You only get one guess as to which page it is. Yes, the first page of the aria.

See how the score jumps from page 44 to 47? 45 & 46 are missing in action.

Did someone rip it out? …a water-sprite unable to follow civilized rules in a library? Talk about getting into character..!

I was thinking about singing it. Yes I know, I’m a guy. But it sits in the same keys as two tenor pieces with which it might have some superficial resemblances

(…NOT like Arlen’s tune by the way!),

namely

1) “O Paradiso”– Meyerbeer

2) “O terra addio” (which is a duet not an aria…)–Verdi

In both cases I think the composer was trying for something gentle rather than imposingly difficult for the singer. The high notes for these (meaning the Verdi & the Meyerbeer) don’t have to be big and loud, although haha that doesn’t stop singers from turning the bel canto into can belto. But in fairness none of these operas are bel canto, they’re all grand operas.

I’ll be seeing Rusalka Saturday night, including Sondra. The librarian said the production is wonderful having seen the dress rehearsal yesterday.

Oh boy.

I was among the audience present at the Ernest Balmer Studio for the birth of Amplified Opera, the brain-child of Teiya Kasahara & Aria Umezawa, in the first of three different programs to launch a new opera company.

Directed by Aria, The Way I See It was a fascinating combination of music & story-telling from two artists describing their experiences with blindness.

American mezzo-soprano Laurie Rubin did most of the talking and all of the singing.

Mezzo-soprano Laurie Rubin

Canadian pianist Liz Upchurch played the piano, sometimes dialoguing with Laurie, sometimes offering her own perspective.

Pianist, vocal coach and pedagogue Liz Upchurch

Virtuosity is almost incidental to this kind of testimony, an authenticity that makes it somehow irrelevant as to whether the mezzo can hit the high A in the aria or not, the notes the pianist plays being a kind of confessional concert music. As a matter of fact Laurie does have a beautiful voice, stunning down low & wonderfully accurate up top. And Liz is an extraordinary collaborator. While her sensitive playing has always impressed me I never knew she had any issues with her eyesight, making me suddenly think of people like Ray Charles or Stevie Wonder. Does the weakness in one sense lead to an enhanced ability in other senses, better hearing? Perhaps. Yet what mattered was the vulnerability, the authenticity, and not intonation or skill.

After the music-drama of songs & personal storytelling we had one of the more probing talk-back sessions I’ve ever seen. It made for a complete meal, given that the discursive doors opened in the show gave us several possible directions for investigation. I’m eager to see how the format plays out tomorrow night, pursuing a different subject, as it will be Teiya in the spotlight this time, again leading to a talkback session.

I believe Aria & Teiya must be proud that their first program appears to be living up to their ideals, as they laid them out in a recent interview. Yes we heard some Copland, some Brahms & Fauré, Mahler & Rodgers, Bach for piano, a Rossini aria. That’s an academic concern, really, and peripheral to what we were really experiencing, in this wonderfully unprotected exploration of life. The lens for what we were seeing might have been blindness, but that too might be incidental. The point is that Aria & Teiya brought Liz & Laurie together, facilitating our experience tonight.

For years I’ve been asking whether opera is dead, given that the same few works make up 99% of what gets presented, the same misogynistic story-lines persist while new works tend to vanish, rarely given a second production.

Amplified Opera would suggest the medium is alive & well.

Ernest Balmer Studio, 9 Trinity Street

Tickets: $25 at door, or online at www.amplifiedopera.com

More information: www.amplifiedopera.com

Tonight’s Toronto Symphony concert reminded me of someone I haven’t thought of in ages, a piano teacher in my teen years. At every lesson we’d begin with small-talk, and then he’d say “now play for me!” It was a wonderfully intimate invitation, making the music-making into a kind of communication, and very personal. It made me feel that he wanted to see what I was doing and that what I was bringing to him each week was a kind of gift, making me feel special (even when I wasn’t thrilled with how a piece was going).

He inspired me.

I was reminded of that magical chemistry as I watched the TSO playing at Roy Thomson Hall tonight, a huge difficult program that they’re repeating Thursday & Saturday:

Did I say it was a huge difficult program? I loved three of the four pieces, although all of them were challenging. Yet the orchestra played like a bunch of kids wanting to impress their new best friend: Gustavo Gimeno. It doesn’t hurt that he knows how to lead them, with a solid beat, a sense of meter and clear interpretive ideas.

TSO’s CEO (left) interviews incoming TSO Music Director Gustavo Gimeno

The piece that I didn’t love? It’s not the orchestra’s fault. Tchaikovsky’s Tempest piece is about 5 minutes too long, a series of lovely episodes and one too many climaxes. It ends with a stunning elegiac passage that reminds me of the ending of the Manfred Symphony¸ although it would be hard to find two dramatic works more different than Byron’s Manfred and Shakespeare’s Tempest.

I suppose the word “kitsch” is in my mind after Wilson’s take-down and deconstruction of Puccini at the COC, although what impressed me was how Gimeno got commitment from his players. A conductor can’t have his players only making an effort when they’re playing a brilliant high-quality score, oh no; they need to play even when it’s schlock. No the quality of the piece didn’t stop anyone from putting their heart boldly & lovingly on their sleeve, and that’s what a conductor wants ultimately. There were stunning moments when you saw the beginnings of a beautiful relationship. The cellos en masse emoting a big romantic melody, the trombones & tuba in a perfect choir, the horns (!) both at the beginning & ending making magic..? THAT is why I thought of my piano teacher, watching the eye contact as Gimeno seemed to invite his players (the orchestra he is about to lead after all): to play for him.

And they did so.

The other three works are the reason you should try to get to this concert.

Pianist Beatrice Rana

I reviewed Rana’s debut CD of Chopin & Scriabin back in 2012, a masterful display of technique coupled with a very mature sensibility. She has wonderful taste, as she showed us tonight. The Prokofiev is an invitation to bring out different facets of her playing in the varieties of sound she gave us. We started with soft relaxed noodling that led to moments of big angular octave passages, easily penetrating the thick orchestral textures. Whether it’s more Gimeno or Rana, we always heard the solos clearly, sometimes floating on the orchestral waves, sometimes sparkling in their firmament. This is the most impressive display of piano playing I’ve seen in awhile.

Because we screamed so enthusiastically for her, Rana honoured us by playing the 5th Chopin etude in E minor as an encore, a stunning jewel.

The TSO concluded with the Ravel, Gimeno illustrating a maxim that’s deceptively simple. To make a good crescendo you have to make sure you start softly. This might be the softest beginning to this piece that I’ve ever heard: making the inexorable build-up that follows so much more powerful, so much more beautiful. Much of the piece was kept in check, so that when a big loud brass passage spears out of the surrounding texture, it’s that much more effective if it’s in the midst of mezzo-piano or mezzo-forte, rather than an orchestra already blaring away at forte. Not only does this spare the audience –who maybe shouldn’t hear everything blared—but it also conserves the chops of the players. It was an especially busy night for the brass: and they were excellent.

To open, we heard something more than a mere curtain raiser. Gimeno explained in a post-concert talk-back, that the piece, titled “Aleph”, which is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, is an apt symbol of the beginning of Gimeno’s relationship with the TSO.

The piece was more than that however. I only wish I could catch the concert again later in the week, as I suspect it will get better. New music is always a challenge, not just to learn how to play, but also in the more fundamental sense of discovering what it’s really doing, knowing how to listen. The first time you play a piece you’ve heard others play is a different level of difficulty from making sense of a brand-new composition. Connesson’s work is fascinating composition that I want to hear again. It features a lot of odd bar-lengths, the meter elusive to perceive, and likely a stiff challenge to the players AND Gimeno. His background as a percussionist seems to be exactly what the doctor ordered, as the orchestra seems ready & willing to follow his lead. At times this piece reminded me of Frank Zappa especially in the long & daunting passages for unison percussion, executed brilliantly I might add.

The concert will be repeated Thursday & Saturday, Oct 10 & 12.

The composer centennials & bicentennials may be artificial stimuli to research, but the effect is real. Knowing that everyone is suddenly focusing upon a particular period seems to inspire all sorts of interesting studies, conferences where people share their research and even get some ideas. It can perhaps be the difference between something languishing in obscurity or finally getting enough attention to be published.

I stumbled on something in the library.

One day while driving home, I’d happened to hear a performance of the first “Valse oubliée” of Franz Liszt on the radio in the car: my usual place to hear music.

So I went to the library to get the music, which is one of the few Liszt pieces I play that I don’t own.

(although it turns out that I did…

Funny that I had forgotten…

hmmm literally a forgotten waltz).

When I think back, I realize that it’s one of several pieces I first encountered in Vladimir Horowitz’s “Homage to Liszt” album of live performances, an album dating from the early 1960s that someone brought into the house, forever ruining me.

There may be better performances out there but each of these has burrowed a deep hole in my psyche, as I realize now that I have attempted to play each piece on the album:

Most of the time I think of myself as a Canadian but there are times when I feel connected to the country where my family came from. Reading the poems of George Faludy, listening to Bartók or Kodaly, my heart swells with Hungarian national pride. And especially when I play Liszt, when I am hearing Horowitz playing Liszt: then I identify with the composer & virtuoso.

In each case I ruefully admit decades later that I was as totally under Horowitz’s influence as if he had been whispering instructions into my ear.

Flash forward to my recent trip to the library in 2019, finding a new edition of the four Valses oubliées, plural. While I had always known there were others besides that first one, I had never listened to the others, never encountered them, never seen the music. The new edition had a Preface dated 2010, the inscription for the new acquisition by the library was dated from the summer of 2011. Was this a project inspired at least partly by the Liszt bicentennial, I wondered?

Liszt was born Oct 22nd 1811

(a cool number when you think about it: 22-10-11),

on the cusp of Scorpio I suppose.

I had known even in childhood listening to Horowitz playing the #1 that this must be the first in a series if it was numbered.

But this edition edited by Peter Jost takes me far deeper into the process of Liszt’s compositions, partly because I’m looking at the entire group of four forgotten waltzes, partly in response to an inspiring preface by Mária Eckhardt.

Eckhardt is co-president of the Liszt Society & a great authority on Liszt.

Pardon me if I stop for a moment to muse about those titles. Valses oubliées, or forgotten waltzes..? If we were hearing old tunes that had been forgotten, that might be odd enough. But when you listen to these pieces, Liszt is doing something else, resembling a stream of consciousness. The tunes are fragmentary, almost as though we’re seeing the process of remembering and forgetting writ large in the scores. We seem to capture the bits of a melody but can’t fully remember.

Look at that first one. I’m fond of Horowitz so why not play one of his wonderful performances, pushing the virtuosic envelope of the piece. It can be played slower (for instance, the way I play it…). We’re in a realm that’s asking questions, making some rhetorical gestures that don’t always lead to the usual slam-bang finish: as this is the late Liszt. He is a different man with a different understanding of his instrument, of virtuosity, of life itself.

Perhaps I should mention his life-changing accident, a fall leaving him wounded, unable to walk as easily, confronted with mortality once again after living to see two children die before him. The piano perhaps had now become something new, no longer a vehicle for effortless expression, but a mirror to mortality, disability. Did he experience pain while playing, I wonder? But that doesn’t mean he wrote music that was easier to play.

And that’s just the first one.

Eckhardt’s Preface is illuminating. We read about his Romance oubliée published in 1881 in different versions, a work employing a melody Liszt had written decades before.

Liszt’s work on the Romance oubliée apparently provoked a strong emotional reaction within the nearly 70-year-old composer, for shortly thereafter, in the summer of 1881, he composed a valse oubliée. The piece was written after he had suffered a fall on the staircase of his Weimar residence on 2 July and was obliged to keep in his bed to eight weeks. During this time he had ample opportunity to reflect upon his life and works.…

“Oublié” (forgotten) became a kind of emblematic concept for the composer: it stood for remembrance and at the same time, for certain musical forms and genres that time had passed over…

While not disclaiming virtuosity or elegance, Liszt permeates the piece with nostalgia and irony, and alludes to the historical position of such pieces by embedding typical melodic and rhythmic formulae of the salon waltzes into an innovative, non-tonal framework that is characteristic of his late style. However, the romantic title page of the first edition, which is adorned with colouful flower, a sleeping genius,, musical instruments and a ribbon inscribed “Souvenir,” does little to convey this aspect of the music.

Eckhardt is being scholarly in confining her commentary to that which is certain. I like to speculate even if I don’t really know.

Only the first has been performed so regularly as to become a familiar work. I don’t believe it’s because the other three are inferior. Perhaps they’re so quirky as to make themselves automatically obscure, the province of nerds & scholars.

I wonder though if we’ve really penetrated yet, as to how one properly plays these pieces. There’s room for whimsy & playfulness possibly something else that I haven’t imagined.

Here’s #2

I sense that the most important part of each of these compositions is in the final minute or two, the reflective passages that are still and soft, retrospective. Liszt contemplates life and virtuosity from a place where his body isn’t working quite so well, both as an older man and perhaps as one at least temporarily disabled by injury. Those bits of melody suggest a process of one grasping for fragments, reminding me of my poignant family encounters with dementia. Whether it’s the mind or the fingers or the body imposing limiting factors, the fragility of these creations grabs me, even if so far they haven’t become popular.

And here’s #3

The waltzes are quirky, at times reminding me of something you’d hear from a circus calliope, at other times as delicate as a memory in the mind’s eye. It’s not a big jump from here to the waltzes in Der Rosenkavalier, ranging from one key to another without worrying terribly about beginning middle & end. Maybe I’m asking too much, but I wish that an interpreter could make more of these madhouse variations (another phrase stuck in my head, as I recall a show from years ago).

And here’s #4, the shortest of the set.