I may seem to lead a divided life, vanishing into realms of violins and sopranos, opera and oratorio, without much apparent connection to the struggles of people in the 21st century: with the possible exception of the singers trying to make a living.

But this year seems very different. It may have begun with the surprise outcome of the American Presidential Election in November. And now as performing arts companies are at least nodding towards our Sesquicentennial, history rears its head in the most curious places:

- Earlier this week the Toronto Symphony presented Accused a song cycle showing individuals confronted by oppressive regimes across different centuries, languages & cultures. Their New Creations Festival a few weeks ago was especially edgy this year.

- Kent Monkman’s pictures at the University of Toronto hold up a mirror to a cultural genocide

- Each of Tafelmusik and Toronto Consort offered a musical reflection on our relationships of centuries ago with the Indigenous peoples of this continent

- The Canadian Opera Company are now rehearsing Louis Riel, in a production with a revisionist approach to this opera about Canada and its colonialist past

- The Straub-Huillet retrospective at TIFF (still with a little over a week to go) has been offering several films challenging the usual understanding of history and power

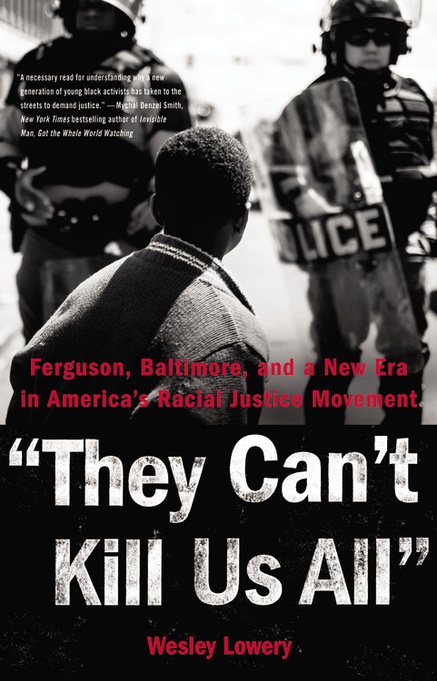

They Can’t Kill Us All is the title of Wesley Lowery’s book. I heard about it via Matt Galloway and Metro Morning on CBC. I remember thinking somehow that I wanted more, that there was something elusive, unsaid, that needed to be articulated.

And now I’ve read the whole book and even after finishing I still feel the same thing. Wesley Lowery does some great things in this book. He’s a young journalist, going around the USA assembling stories of the resistance to racism, protests inspired by horrific shootings. We know the saying “Black Lives Matter” that has spawned a movement in social media and elsewhere . The book is a very useful primer because it helps give you a clear picture of who’s who, of what happened where and when, going beyond the superficiality of TV and twitter.

And yet he stops short of what I hunger for.

(How do I put this?)

Lowery is not James Baldwin or MLK. He stops short of making the big sweeping statements. He’s a journalist and very factual, very careful in his statements, and certainly not a poet or a preacher.

And he’s a black man treading carefully at a very dangerous time. The quintessential narrative would be, the black man in the presence of police, being super careful not to give offense: and getting shot anyway. The book has to reference this template both in the incidents reported and in Lowery’s own polite language. He stops short of calling the USA a racist or fascist country. The book is factual.

As a white Canadian perhaps I can say what’s missing.

The title hints at what’s underlying this book and under the surface of black life in America, the implications underlying the phrase “black lives matter”. If you need to say it, then clearly it’s in question. The horror underlying the assertion that “they can’t kill us all”, is that no one is safe, that the unthinkable needs to be put into words: as though everyone really could be killed, that some of the racist element in the USA might even want that. After reading Monkman’s text in his exhibit –where he chillingly quoted someone speaking of “the final solution” to the aboriginal problem—I think reconciliation must be far more radical, far more profound in its goals, whether we speak of indigenous truth and reconciliation, or the equivalent conversation concerning black lives in USA.

There is one very powerful moment that might sum up this attitude, the clear statement Lowery would make, concerning the current limits of action. Brittany Packnett, who Lowery describes as a “thirty-one -year- old Ferguson protester”, told him a story.

One evening when she was eight years old, her father and younger brother came bursting through the front door, her brother in tears. They had been out for a drive and had gotten pulled over. As the officer had approached the vehicle, he has asked Mr Packnett to step out of the car, and then had thrown him onto the hood and put him in handcuffs. The officer didn’t believe that this black man could possibly own the Mercedes he was driving.

The entire family was outraged, and Packnett’s brother was traumatized. Her father, who was among the most politically connected black men in St Louis, called the police chief and demanded that the officer apologize personally, in front of his son.

As she grew older, Packnett became an outspoken minority in her predominantly white private schools, sprinkling her class assignments with asides about equity and racial justice and helping to organize a regular seminar on diversity and inclusion. That drew backlash in the hallways of her majority-white high school. She recalls that one particular student, a young white man from a prominent local family who was a year ahead of her, began following Packnett around in the hallways, mocking her. “Is my whiteness oppressing you today?” he would ask as she moved from class to class. She would ignore him. Then, one day, she didn’t. She turned around, just outside the women’s locker room, and told him to stop speaking to her that way. In return he spit in her face.

Packnett said her track coach, one of her mentors in high school, insisted she tell the principal, who forced the boy to apologize. Immediately, the memory of her late father’s interaction with the officer who pulled him over flashed back into her mind. That officer like this boy, had been made to apologize. But had either actually been held accountable? Or did the system send the message that abuse of a black body can be negated and papered over by an “I’m sorry” no matter how reluctantly uttered.

“It’s this idea that all a person had to do was say ‘I’m sorry,’ and then they never had to be held accountable for their actions.” Packnett said. “Thinking about those two incidents is, for me, a constant reminder that this system was never built for us in the first place.”

(Lowery 228-9)

When you plunge into a dark lake you need to know how to find your way to the surface and to the shore. I came up for air regularly as I read the book,

- grateful to be Canadian

- grateful to be white, even if that carries some responsibility: to be helpful and active rather than to passively hide away in my safe hidey-hole

- and wondering what it would be like to be raising sons, particularly if I were black

Watching the news in 2017 it seems to be a troubled time in the USA. During the election campaign, Donald Trump claimed that it’s worse than ‘ever, ever, ever’ for black people. With his victory over Hillary Clinton, the phrase has a curious resonance now.

Barack Obama turns up in this book, and he’s a fascinating reference point, the obverse side of that reflective template that recurs throughout the book that I mentioned above, black man encountering police. Obama as President is the dream, while the police shootings are the nightmare, each a benchmark of the same sad fact: that the civil rights struggle is far from over. The election of a black president was supposed to signify something, but if anything it signaled a renewed push back from the extreme other side, the alt-right, the KKK, those who resented Trump’s presidency. Sadly, little has really changed, especially in the deep south.

They Can’t Kill Us All is not a book to show you the path forward, so much as a forensic examination of the labyrinth in which we’re currently stuck. Nobody seems to know the path forward, although to his credit, Lowery speaks to the new generation of young activists who will be part of any coming transformation. This is a compassionate and methodical journey to several front-line encounters, uncensored and direct.

If you’re needing motivation, if you want to read and get angry, this book can work for you. I wanted something a little more strident, but found it very polite, not unlike the young black man who has to walk carefully, for fear that he might trigger something by seeming too strident or dangerous. I was kind of heart-broken by this book. If you think Afro-Americans have made progress and that the civil rights movement is over, you should read this book. I need something more to feel better about my place in this society. I recall feeling un-moored and dizzy coming out of Monkman’s show, and this is somewhat parallel. I hope the black experience in Canada is better than this –oh my God I hope so—particularly with police. I can’t help feeling humbled, that as a white person I have privileges and a safer status.

And we’re still a long way away from true reconciliation.

Toronto – Louis Riel, composed by Harry Somers with libretto by Mavor Moore, is a uniquely Canadian contribution to the opera world. First performed in 1967 and last performed by the COC in 1975, Louis Riel returns to the stage in 2017 in a new co-production between the COC and National Arts Centre (NAC) that works to revise the opera’s colonial biases and bring forward its inherent strengths and power. Louis Riel runs for seven performances by the COC on April 20, 23, 26, 29, May 2, 5, 13, 2017 at Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts before making its way to Ottawa to be presented by the NAC on June 15 and 17, 2017.

Toronto – Louis Riel, composed by Harry Somers with libretto by Mavor Moore, is a uniquely Canadian contribution to the opera world. First performed in 1967 and last performed by the COC in 1975, Louis Riel returns to the stage in 2017 in a new co-production between the COC and National Arts Centre (NAC) that works to revise the opera’s colonial biases and bring forward its inherent strengths and power. Louis Riel runs for seven performances by the COC on April 20, 23, 26, 29, May 2, 5, 13, 2017 at Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts before making its way to Ottawa to be presented by the NAC on June 15 and 17, 2017.