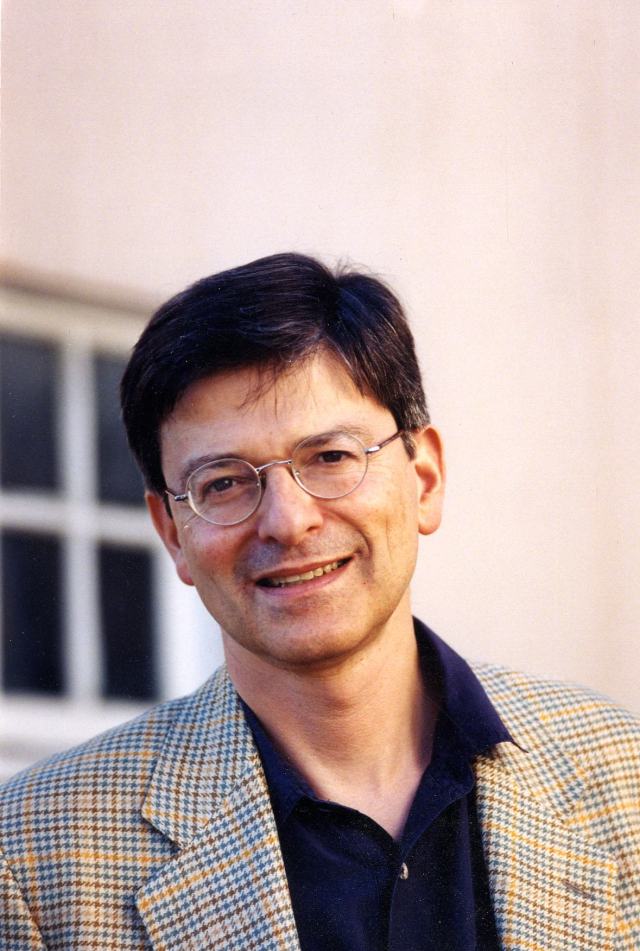

Evan Webber is a writer and performance maker who lives in Toronto. Evan’s work considers the relationship between time and text, and between narratives and institutions.

Evan is an Associate Artist of Public Recordings, a collaborative operation that conjoins artistic research, performance creation, learning, and publication. And he is curator of the HATCH performance residency at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre. His work’s been shown across Canada, Europe, Australia and Japan. Evan is a graduate of the National Theatre School of Canada, where he is now a guest instructor.

And In May Evan Webber’s play Other Jesus will receive its Toronto premiere through Public Recordings. I took the opportunity to find out more about him and the project.

Evan Webber (photo: Sarah Bodri)

Are you more like your father or your mother?

I can’t muster any objectivity on the subject of parents. My mom and dad have both lived what I would call difficult lives–lives that have taught them a lot about the difference between loneliness and being alone. They are spiritual people, however, and their practices provide them with powerful sustenance. I suppose I am like both of them in the respect that I also look to be sustained not only be material means.

What those other means are I don’t know but presumably art has something to do with it.

What is the best or worst thing about what you do?

Public Recordings’ ongoing project is to make time-based artworks in order to learn about the nature of togetherness, on the ways that groups of people might work collectively, and how they come to share in the projects and feel agency to change them. My own way into this practice is through writing and I take special pleasure in continually re-discovering how this putatively solitary act is, in fact, most lively as a collaborative one. Creating and producing and trying to reach a public through collective means is a lot of hard work but there is nothing bad about it. There’s no worst thing.

Who do you like to listen to or watch?

I really liked listening to Fred Moten and Robin Kelly speak with each other last Wednesday. The hall, which at least three people said was like a Harry Potter set, was packed with people. Moten and Kelly were talking about black studies & indigenous studies & ecology, joy, counter-mapping, the State of Israel & the People in Israel, anti-intellectualism, and how scale is the enemy of the renewal of sociality.

What ability or skill do you wish you had, that you don’t have?

I would be a better accountant–an accountant in the first place. I really appreciate specialized knowledge, especially of mechanics. But I don’t know much about this.

When you’re just relaxing and not working, what is your favourite thing to do?

I like cooking and doing the dishes.

*******

More questions about the creation & presentation of Other Jesus

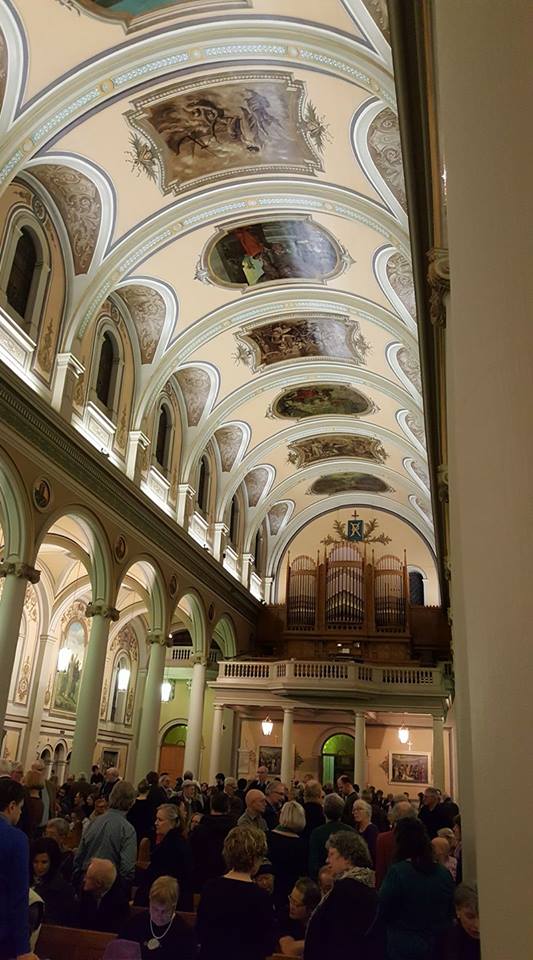

Other Jesus is being produced in collaboration with St Matthew’s United Church and will be presented inside a church space. Please talk about your relationship with the church, both in their role in the creation and how your text places you in- or outside a church with all its politics.

We didn’t want to do the play in a church. I was worried that if we performed in a church people would think the work is about religion or rationalism or atheism or something. We thought that if people walked into a church then they wouldn’t be able to read any metaphor in the story. In the play, religion is a cypher for the way stories produce power in and among people with precarious lives, which, sooner or later, is everyone.

I guess we were imagining some kind of archetypal church when we developed this opinion; some patinated, vaguely sinister old institution. When we visited St. Matthew’s we encountered a very different reality. It’s a community space in flux; it’s in a process of becoming and its future as a ritual space is far from certain. Most places like it in Toronto are being sold to condo developers. Inasmuch as it’s space where people just experiment with doing things together the church feels very familiar. (There are probably about as many people who regularly attend the United Church services as people who regularly attend experimental theatre and dance, another common point.)

The text of Other Jesus is about institutionalizing practice and the role that performance plays in the process. It’s about how things come together and how they fall apart. And the church itself offers a beautiful and complicated example of this process.

I read that your director Frank Cox O’Connell, said this about you Evan:

“Evan began the process by trying to write an adaptation of the Gospel – but what he ended up writing was a very personal text about trying to believe in something and belong to something when you feel like you’re living at the end of the world. I loved it. I found it strange and fun and ambitious and heartbreaking. I’ve been working with Evan for almost 15 years – this is his strongest work. –”

Please elaborate on this

I was interested in appropriating the “creative strategy” of divine inspiration as a system for writing because to me this is actually the official doctrine of whatever part of capitalism we’re in right now: if you don’t have a lot of capital already, you really need to hope for the best and trust the system to disclose its inscrutable truths. I wanted to really commit to that and see what it produced. So my version was to simply sit and write a gospel, word by word, without any editing, beginning at the beginning and ending when I had to stop, which was usually about fourteen hours after I started. (I repeated this process four times with a lot of research and planning in between.) It’s really a record of my attempt to stay present and receptive to my own imaginative or regurgitative capacities. Incredibly, my collaborators on the project were not only committed to staging the work, but to extending the logic of my formal writing constraints: learning, word for word, this halting document of material experience and trying to act as though it were a kind a naturalistic launch-pad into the supernatural.

I think Frank is wrong in saying it’s my strongest work. It’s absolutely the weakest by the measures of originality and coherence and it’s full of things I would normally consider to be errors. In this sense I would say that it’s authentic, however. I’m curious about how that will feel.

Is there anything you would want the audience to do to prepare for Other Jesus, anything we should read or study? Would it be better to look at the Bible, to forget anything we ever knew about religion: or somewhere between those two extremes?

Matt Sergi, who is theatre scholar at U of T, said at a talk before a performance the other day, “Think about what you know about this story, about what it means, and as you watch the show, try to see how it articulates a contrary meaning.” I found that suggestion widely applicable.

Could you quickly place this in a religious context for us, and how Other Jesus is in some respect a response to your spiritual crises, or the result of your spiritual evolution?

It feels absurd to say that Other Jesus isn’t about spirituality but, for now, I will. I would say it is a response to material that is shared, the story of Jesus and his disciples. And I would say that my community and perhaps my society are presently enduring a crisis of sharing.

Are there any shows you’ve done or seen that now seem to have laid the groundwork for what you’re doing in Other Jesus?

The groundwork is in Public Recordings’ big collaborative works and especially an ongoing writing project I co-created with Ame Henderson called performance encylopaedia which we last did in Toronto at the Art Gallery of Ontario. I’ve worked with Frank Cox-O’Connell for many years too, and we have a shared interest in the problems of canonical western narratives–this work resumes our conversation on that subject. Shows I’ve never seen exert probably the greatest influence because I’ve had to imagine them: Brecht’s unfinished God of Happiness, for example, and Fassbinder’s Blood on the Cat’s Neck. Through the wonderful writer Stephen Mitchell, I discovered that Thomas Jefferson wanted to make a Bible that scrubbed out any mention of magic. He thought the young United States of America deserved no less. The complications posed by magical powers in Other Jesus reflect on this–the potential of the unwritten.

Please talk about how you came to be involved in this project.

I was invited to join the Tarragon Theatre’s playwrights’ unit by Andrea Romaldi. The playwrights’ unit is a yearlong commitment for a group or writers who share their work and have it read publicly at the end. It was interesting to be invited. I never imagined that my work aligned with the Tarragon’s interests. But the context gave me a lot to push against, and the constraints produced the work over the course of the year. In the end I found I had a lot more in common than I had initially supposed.

*******

What’s the difference between a person and a story about a person?

Toronto’s award-winning Public Recordings stages a new play by Evan Webber. In the occupied territories of ancient Judea, a group of spiritual workers consider what’s real while trying to break even–until one of them turns out to have the magic touch. Other Jesus is a performance on the risk and reward of believing and belonging.

Text & Dramaturgy by Evan Webber. Direction by Frank Cox-O’Connell. Scenography & Costumes by Sherri Hay. Music & Sound Design by Christopher Willes. Lighting Design by Ken MacKenzie. Production Management by sandra Henderson. Additional collaboration and performance by Courtney Ch’ng Lancaster, Ishan Davé, William Ellis, Thom Gill, Ame Henderson and Liz Peterson.

Produced by Public Recordings and EW & FCO. Co-Produced by Festival TransAmériques. Created with the support of Tarragon Theatre’s Workspace, Videofag and St. Matthew’s United Church.

Toronto Premiere

May 6-14, 2017

Tuesday-Sunday, 8pm

St. Matthew’s United Church 729 St Clair Avenue West, Toronto

Box Office Information:

$25 General

$20 Arts Worker/Student/Senior/Under Employed

Advance Sales: 416-531-1827 // publicrecordings.org/otherjesus

Tickets available at the door

or here.

Lepage is of course the consummate theatre artist, one of the country’s great exports, thinking of opera productions via his company

Lepage is of course the consummate theatre artist, one of the country’s great exports, thinking of opera productions via his company