Director, dramaturg and playwright Peter Hinton has worked across Canada with many theatre companies. He has been the Associate Artistic Director at Theatre Passe Muraille and the Canadian Stage Company in Toronto, Artistic Director of the Playwrights Theatre Centre in Vancouver, the Dramaturg in Residence at Playwrights’ Workshop Montréal, and Artistic Associate of the Stratford Festival . From 2005 to 2012 he Artistic Director of the National Arts Centre English theatre, where he created a resident English theatre company, with actors from across the country, and programmed the NAC’s first season of Canadian plays.

His own plays for the stage include Façade, Urban Voodoo (written with Jim Millan) and a trilogy of three full length plays entitled The Swanne — George III: The Death of Cupid(2002), Princess Charlotte: The Acts of Venus (2003), and Queen Victoria: The Seduction of Nemesis (2004). Eleven years in the making, all three plays premiered under his direction at the Stratford Festival. In 2006, he co-created with Domini Blythe , and directed the solo work, Fanny Kemble, about the life of the famous British actress and abolitionist.

Peter Hinton has also written the librettos for two operas with composer Peter Hannan: The Diana Cantata, and 12O Songs for the Marquis de Sade, (awarded the Alcan Performing Arts Award in 2002).

Since 1985 he has directed over 75 productions of new plays, classical texts and operas, including premieres of works by Allen Cole (Hush, The Crimson Veil), Blake Brooker (Serpent Kills), John Mighton (Possible Worlds), Michael McKenzie (Geometry in Venice) and Marie Clements (Burning Vision). His production of Gloria Montero ’s Frida K.premiered at Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre in 1995 and subsequently played to sold-out houses in Canada, Mexico City and Madrid. His productions have twice been invited to the prestigious Festival de Théâtre des Amériques (now Festival TransAmériques ) in Montreal: Greg MacArthur’s Girls! Girls! Girls! in 2001, and Marie Clements ’ Burning Vision in 2003. In 2007, he partnered with Britian’s Royal Shakespeare Company in the world premiere of Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad. In 2009, he directed Sam Shepherd’s Buried Child in a National Arts Centre and Segal Centre for Performing Artsco-production. He made his directing debut at the Shaw Festival in 2011 with When the Rain Stops Falling, and returned in 2013 to direct Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan.

He was the recipient of the Jessie Richardson Award for directing in 1995 for his production of Gordon Armstrong’s Scary Stories. In 2009, Peter Hinton was made an Officer of the Order of Canada.

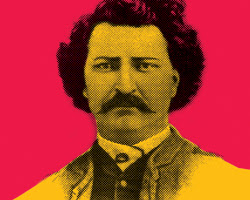

I was delighted to have the chance to talk to Hinton, in hopes that by finding out more about him, we might illuminate his ambitiously revisionist production of Louis Riel for the Canadian Opera Company, opening Thursday April 20th.

Peter Hinton

Okay, let’s talk about you, Peter Hinton, and find out about Louis Riel that way. So this first question is one of influence. Are you more like your father or your mother?

Oh God…

Well, I would have to confess, I am a hybrid of the two. My parents were academics, and valued academic achievement very highly, which of course I rejected (nervous laugh).

How did they feel about you going into the theatre?

My parents were oddly Victorian people. They felt the theatre was something you attended, but not something you did, and so we had many struggles about that. Sort of under the purview of “we just worry about you and want you to have something to fall back on…” which of course I interpreted as “you don’t approve”.

It was a fraught time. My parents passed away when I was in my 20s. And so I regret that among many things, that there was this point in my life when I needed their validation, their approval. And looking back now I wonder why did I need that so badly?

But they were definitely a strong influence, in terms of discipline, work habits.

What is the best or worst thing about what you do (you do so many things)?

The best and the worst thing, is that we’re constantly engaged in problem solving. So many problems. How will we do it with the artists we have? how will we do it with the budget that we have? It’s hardly the bane of my existence, because every day I’m asked to solve problems. But that’s also the centre of your creativity, that a good project has a problem, you expose the problem, share the problem to the audience. It’s a balancing act all the time. There’s a lot of joyous creativity in the problem solving.

Okay, so forgetting all about Riel or opera, what do you like to listen to or watch?

Ahhhh that’s such a good question. I was just noticing the other day that my reading is behind the times, I do so much reading for the projects that I do, but that’s the thing I love about the theatre, that it introduces you to subjects that you wouldn’t normally encounter. Earlier this year I directed a play about quantum mechanics, which I’d always shied away from, and gone “okay I’m not a physics guy, I’ll never be able to understand that”. But actually in preparation for that there was some very interesting writing. And so I try to make up for this. I’ve been reading Zadie Smith’s Swing Time and loving it. I adore Zadie Smith.

I have pretty eclectic taste in music. I love a lot of classical music as well as contemporary music. And certainly having a much younger partner influences my exposure to music. Howard Davis is my partner. I find it a challenge, being in your 50s you’re stuck. I noticed with my parents they were contemporary up to a certain point and then they got fixed in a certain time. And it was very amazing to observe that in myself. The biggest cultural influences in my life stop at the year 2000. I don’t want to be an old—school dated thing, I want to live in the modern world, to be literate in what people are reading and listening to.

Can I segue from that to ask a Riel question? Compared to Mozart or Handel it seems so new and yet an opera written in the 1960s: that feels old in the drama world. Do you feel Riel is new or old?

I think Riel is very much of its time. It carries with it signatures of work that was created in the 1960s. On the one hand it’s really provocative. You can see all that it’s reacting against. It reacts against melody, against linear narrative, against assonance in any way. It’s very radical in its conception. It demands a lot of its listeners. (nervous giggle) You cannot put Riel on as background music. Forget it.

Did you try?

I always like to listen to what I’m working on, in my studio. But it was so impossible with Riel because it’s just so dominant! You must listen to it, you can’t do anything else. And so it has that 60s quality to it, which is both dated, and also really vibrant. I have a similar response when looking at wild abstract expression in paint. Look at a Jack Bush painting, that’s 1962. But there’s something so alive in it as well. And so I have that kind of relationship to it. I don’t know how this piece will stand the test of time, 50 years from now, because there are all kinds of entry points into Louis Riel, that the piece doesn’t speak to, that demand pause, demand reconsideration. It’s a wild thing to tell the story of one of the most famous Métis people, but Somers chose a very European based sound. It sounds like very modernist music that’s mid-20th century. And yet he was someone who was very interested in expanding possibilities, adventurous, very exploratory in range.

And it’s my first official real opera that I’ve directed. And so I don’t have a lot of the reference points that a lot of my collaborators do, who are familiar with 19th century opera for example. And so to me it’s very much of its time but it’s modern too.

We’ve talked a lot in rehearsal that there are really three time-lines that are always in play.

- One is the nineteenth century time-line in which the narrative is enacted

- And then there’s our own time-line, how is this opera received in 2017, how do we as modern people interpret it

- And then there’s this time of the 60s in it, which is interesting too.

And so there are three definitive time periods that speak to each other, and are in dialogue with each other over the course of the opera.

Did you see Robert Lepage’s 887 (on last week)?

No, I’ve just been working on Riel.

I ask because it oriented me to the 1960s and the concerns in Quebec (from Lepage’s youth), about separation and the poem Speak White, as they apply to the composition of Louis Riel in the mid-1960s.

Yes it’s very curious that the opera was conceived very much as an allegory for the two solitudes. It’s impossible to interpret that story today from that perspective. It’s a historical reference point, but the Indigenous aspects of the opera are far more alive and relevant to us today.

It seems the COC really knew what they were doing when they hired you. To be blunt: WHY YOU?

COC Music Director Johannes Debus and COC General Director Alexander Neef. (Photo: bohuang.ca)

Well I think Alexander [Neef] invited me to the project because of his knowledge of the work I’d done at the National Arts Centre with Indigenous artists, and also working with a large institution. It’s a very difficult kind of mix, bringing Indigenous artists into a place that has no experience of that at all. And so I had to negotiate my own position with that very clearly and very carefully, so I could ensure an environment where many voices could be brought to the room, and heard. And there was a willingness on the part of the COC to be influenced and changed by that: which I think there has been.

Alexander approached me because there are few people who could take on that challenge in that way. And I had to think about it a lot, because the Indigenous involvement is really important to me. And I had to figure out how I could direct this story and find the right collaborators to participate with.

There’s risk for you, in your authenticity (being true to yourself) and your relationship to the Indigenous Community. Was that part of your process? Did you experience stress and risk, negotiating your place in this?

Every day! Every single day. That is ongoing.

That’s how art should work. I get the impression (between you and me) that such questions and risks don’t happen often enough.

It’s easy to make assumptions. Every day on this project has been a new negotiation of how the work is interpreted, how to keep it open, and porous in some ways so that there are going to be different responses to it, but also provide guidelines that the artists can feel secure in. And it’s not creating a new piece but dealing with an existent score, an existent text, and how to interpret that becomes really interesting.

And it’s not public domain [like most operas] and so you could also experience push-back from the owners of the score as well. Or maybe we don’t want to talk about that..?

The COC have been very good with Moore’s estate and Somers’ estate, so there was a lot of dialogue about some of the changes we wanted to make and what we would honour in it. I think it’s such an interesting piece, because there are many beautiful, strong strong things in it, and here are also colonial biases within it. And so I was trying to conceive of a production that would shed light on its strengths as well as shedding light on its biases without undermining the piece.

One of the great themes of the opera is this idea of trial. Louis Riel’s trial is a very substantial part of the third act. And yet in the opera there are many things put on trial. Confederation is put on trial. The ideas that forged Canada are put on trial as much as the character of Riel is put on trial. And so in some ways in this production I think of the opera being on trial. And the verdict doesn’t mean it’s a good opera or bad opera, but are its ideas true? Do they uphold to us today? It’s a trial about what needs to be said. And what our future needs to be. This whole Canada 150 is a very interesting phenomenon, because most people that I speak with have a skepticism about Canada 150. What is being quote unquote celebrated, vs commemorated? It’s a hard concept for a lot of people to grasp. And yet it exists, we still do it. And there was an opportunity as an artist to respond to that. I have to say, when I first learned about it, I thought it might be very pro-Canada, “from sea to shining sea” (ironic giggle). Dang! I was really taken with its indictment of our history.

How do you feel about [and I sang it…] “We’ll hang him up the river with a ya ya ya”, which is totally ugly..!? If you’re an English Canadian you’re squirming in your seat.

Racism is front and centre. It’s very critical in that regard.

You know there’s something that has come up a lot. There’s this thing we heard in high school, that Canadian history is BORING? And I wondered is that the Canadian self-deprecation? But in working on Riel I was reminded, there’s like a conscious will to divert us from the atrocity of our history. There’s a huge legacy of injustice. And when they say “it’s boring don’t look at that” is a huge problem we have, and contributes to a kind of cultural amnesia about our history and what we need to reckon with, what we need to be voicing, speaking about… So it’s very challenging on every level.

There’s this quote I have in the previous COC program where you reference John Ralston Saul, and his notion of Canada as a Métis Nation. Could you explain how that’s relevant to Riel?

Well John Ralston Saul’s book A Fair Country opens with that statement. It’s a very historical book about Canada, and speaks about how Canadians sometimes use the colonial bias as the sole means of definition for who we are. And what’s neglected in that perception or analysis is the significant and vital contribution of aboriginal cultures and indigenous cultures to our understanding of ourselves. It’s denying a fact of presence.

And that’s not to undermine or deny any of the history or current action, the cultural holocaust and the legacy of the residential schools and the true abuse. But it’s important that we acknowledge the real commitment and contribution Indigenous societies have made to us and how important and vital they are to our future. I found this book very interesting and very hopeful in a realistic way rather than an ideological way.

Have you met him?

Yes. I met him at the NAC and at the season launch last year. I think he and Adrienne will be there tomorrow [opening night].

I wanted to ask about influences.

It was really important to me that on this production, wherever we could sort of bridge, the people who are cultural advisors would be participants of the show. It’s always odd to me when there’s one group creating and another group advising. And I’ve been so fortunate in my creative practice to be able to work with so many Earth-shattering wonderful Aboriginal performers. So when I knew about Riel having Jani Lauzon involved was a really important collaboration.

Jani Lauzon as The Folksinger and Russell Braun as Louis Riel in the Canadian Opera Company’s new production of Louis Riel, 2017 (photo: Michael Cooper)

Jani and I have worked many times together at the National Arts Centre, Billy Merasty as well. I did a very large project of King Lear with forty indigenous actors in it at the NAC. Billy was part of that as well as a Marie Clements play about Norval Morrisseau that Billy played Norval in. And so it was really important for me to have those guys involved in this show. Because I could collaborate with them, I could get their responses, build something with them based on previous work. And Cole Alvis is a remarkable theatre creator.

Cole Alvis as The Activist in the Canadian Opera Company’s new production of Louis Riel, 2017 (photo: Michael Cooper)

And Justin Many Fingers who’s a Blackfoot dancer from Calgary who I know from my connections there, I’ve always wanted to work with him. So I was trying to continue to build relationships, that’s the important thing. You do one project with someone, and if you connect, if there’s a creativity that comes from that collaboration it’s very important to continue it, to keep the dialogue going. That’s what I hope for the COC that the artists currently involved will continue. So for example Joanna Burt: INCREDIBLE. She’s in there playing Sara. It’s so exciting to see her in the ensemble. And working with Santee Smith, choreographer. Just trying to break down these walls, with big Euro-based institutions.

Now some of this with opera is based on the discipline, no? singing. Can we expect to see Indigenous Opera singers? Or does opera have to change, or at least perform a different idiom?

Well a bit of both. That’s the thing, the first response I hear from people is just “oh no” that they can’t be opera singers, which is not true. And so part of this production is to change that. Part of this production is to draw attention to future change to that. You know there is a very good generation of classically trained singers. But we also have to look at traditions of training. And how training is acknowledged in different communities, different cultures. And there are different traditions of singing.

Yes opera (and its pedagogy) has this traditional association with power and the endorsement of power, from Louis XIV through Hitler & Stalin, and beyond. So it’s not a medium for empowerment necessarily.

Yes I think that’s a positive breakthrough to this production, that it’s really opened ways of working and challenged assumptions about how things are done. You know, from having a smudging at the Four Seasons Centre, and seeing singers sit with leaders of our Indigenous Community. It is very encouraging to me. But it’s also right, it’s the times we live in.

This opera is not perfect, it is a telling, it’s a target for many points of view, many criticisms, all the reasons people go to a live performance. This can engender a lot of dialogue. It’s where we’re at right now.

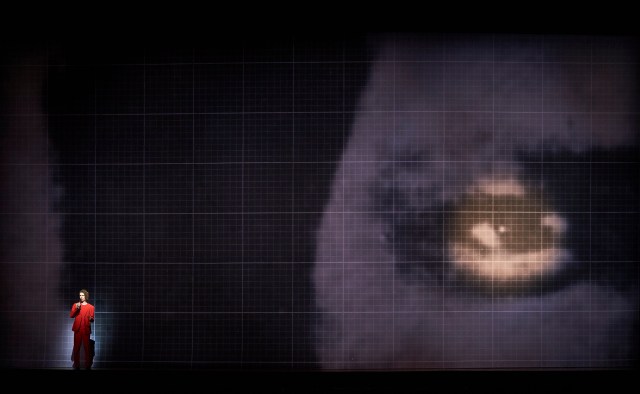

Could you talk about how your use of that split chorus –some singing, some silent—might impact the way we watch the opera?

So I wanted to redraw the lens by which we view this opera, and to remind an audience that this is a history that could have many different viewpoints. That you cannot convey a truth by one perspective, especially when there are such inequities of power. And so the chorus is very important to Louis Riel. They’re really the people on which the soloist characters speak on behalf of, stand for, represent, mis-represent.

Members of the Land Assembly in the Canadian Opera Company’s new production of Louis Riel, 2017 (photo: Michael Cooper)

And so I wanted to counter a silent figure with a singing figure as often as possible, to show a tension between those who have a voice and those who don’t.

Where is singing powerful and where is it just noise?

Where is silence oppression?

Or where is silence protest?

I hope the audience sees that. The audience is a part of it too. The audience is watching. The audience is a presence. I don’t go for this thing that the audience is always anonymous in the dark, that we’re all the same: especially in a place like the Four Seasons Centre, where there are rings and tiers. The strata, a sense of hierarchy. I just wanted to reflect that in the show.

I hope the audience sees that. The audience is a part of it too. The audience is watching. The audience is a presence. I don’t go for this thing that the audience is always anonymous in the dark, that we’re all the same: especially in a place like the Four Seasons Centre, where there are rings and tiers. The strata, a sense of hierarchy. I just wanted to reflect that in the show.

There are enormous contrasts in the show between action and reflection. Waiting. Like every time Riel enters, and the people are doing something he tells them to stop. Every time he comes on the stage he says “stop doing this”. And then he has very private reflective tortured arias. They’re not unlike Hamlet. “One must act, but what must I do? Who am I acting on behalf of? Am I called by God, am I called by the people? ” And then he’s interrupted by this enormous onslaught of action. I tried to reflect that on a lot of different levels.

One thing I really love about it is that, for the first time at the Four Seasons there are Indigenous performers onstage playing Indigenous characters. So when the curtain comes up it’s a very long sequence, at the top where it’s about the Indigenous performers looking at the audience as the audience is looking at them. It’s a real moment of dramatizing contact, who’s seeing who, who’s discovering what. That kind of tension runs through the opera and is reflected in the staging.

Is there a teacher or influence you’d care to name that you especially admire?

When I was emerging as a director, thirty years ago, I was very fortunate to have a kind of mentorship with Larry Lillo. Larry was the artistic director of the Vancouver Playhouse. He gave me a lot of opportunities when I was young. He was very tough on me. Very rigorous. And very loving. And I am always very grateful to Larry for those opportunities.

And you’re going off to another show in two days?

Yes I go back to the Shaw Festival, where my home is. I’m doing a wonderful play called An Octoroon, that I start on Tuesday. And I’m going into my seventh season at the Shaw. But this year has been uncharacteristically busy. Busier than I like. I’m not as young as I used to be.

Do you manage to get to the gym? (laughter) Did you get any sleep this week?

This week? Forget it. Three years ago I was in my best physical condition, because I was performing and vain enough (laughter) It’s a great motivator. It’s harder with direction because you send a long time sitting and watching other people. It’s so mentally active and yet so physically sedentary. It’s a balancing act.

I wanted to insert a picture of the pugs who boisterously made their presence felt at one point in the interview.

*******

But before Hinton’s production of An Octaroon at the Shaw Festival first there’s the Canadian Opera Company’s ambitious production of Harry Somers and Mavor Moore’s Louis Riel, opening Thursday April 20th and running until May 13th.

Pingback: Hinton’s Riel: protocols for reconciliation | barczablog

Pingback: Georgia O’Keeffe at the AGO | barczablog

Pingback: Mixie and the Halfbreeds | barczablog