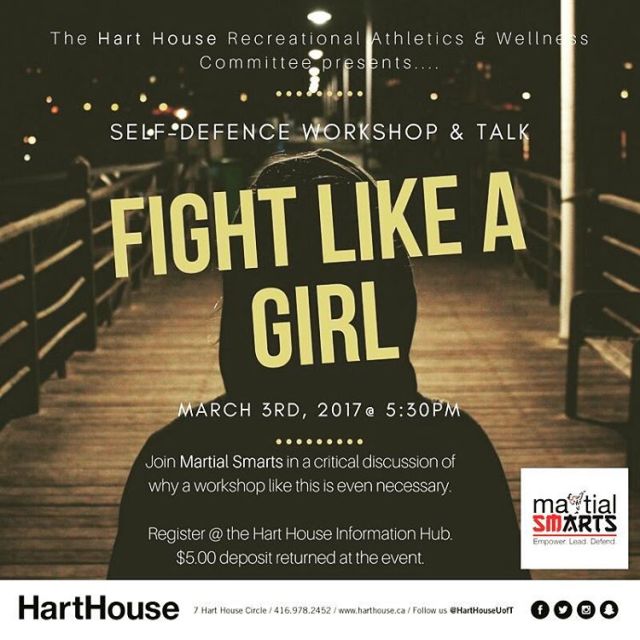

The words on the poster caught my eye. “FIGHT LIKE A GIRL”, all in capitals.

When I inquired further I discovered Martial Smarts and then its founder Dr Ryhana Dawood: a strong advocate for women’s health and female empowerment through self-defense. As a resident physician and double black belt, she has worked with hundreds of women across the GTA and overseas leading self-defense workshops for many underprivileged groups, schools and universities.

Ryhana founded Martial Smarts, a non-profit organization based out of Toronto that aims to teach proactive and reactive self-defense and situational awareness based on the principles of Karate and Taekwondo.

I wanted to share this remarkable story of empowerment by asking Ryhana a few questions.

Are you more like your father or your mother?

I am like both. My parents are both strong-willed people, both in their own unique way. I think I get my work ethic from my father. He is the most hard-working person I know. When he is assigned a task he dedicates all his time and energy to complete that, going above and beyond expectations. Watching him do this throughout my life has definitely helped me realize that our accomplishments and successes are a direct result of the amount of hard work we put in. That is what separates us from the pack. Keep working even if it’s only you, even if the going is slow and your goals seem unreachable.

I am also like my mother. She raised us to be independent, self-sufficient and people of integrity. She also emphasized that whatever a boy could do, a girl could do, and whatever a girl could do, a boy could do too. As such, my brothers, my sister and I were all taught the same things, put in the same lessons and expected to live an active lifestyle while also learning how to take care of things at home. My mother is free-spirited, curious, dependable and unique. I believe growing up with such a wonderful person has helped me become similar to her.

Lastly, both my parents are deeply spiritual people. They brought us up to be God-conscious, socially responsible, respectful, generous and loving people. These are the principles that Islam also teaches and qualities that I have attempted to and continue to further develop. Out of all the things that they have taught me, the most beautiful gift they have given me is most definitely the gift of Islam.

What is the best thing about what you do?

The best thing about what I do is bringing women from all different ethnicities, religions and socioeconomic backgrounds together – empowering women to, in turn, empower others. I’ve always been told that if you want to see real change in the world, teach a woman a skill because she will use that skill to help all those around her. I’ve tried to use this principle with Martial Smarts. It’s really beautiful to see the effect of my workshops. Almost immediately you see women begin to feel more comfortable, confident and strong. They realize their own potential, build their self-esteem, quite often regain some of the confidence they have lost and learn how to lead a more active lifestyle. Our workshops focus on improving overall health, as well as learning basic self defense. Women come in believing they are learning how to protect their bodies but they leave with something even better – the confidence to take on the world.

I love that Martial Smarts allows me to combine my knowledge of medicine and martial arts with my love for community work, activism, mentoring, uniting others and travelling. It is the perfect vehicle to achieving my dreams and I can’t wait to see where we end up.

Who do you like to listen to or watch?

Toronto Raptors, Toronto Blue Jays, represented family time growing up. Played basketball competitively so have always been drawn to it. Enjoy supporting the home team and have been following them since I was about 8 or 9 years old. I don’t have a lot of time to watch movies or musicals and I’m not a radio person, but if I had to choose my favourite movie it would definitely be Disney’s Mulan – for obvious reasons I really identify with her. We have a lot of family discussions which are lively and varied in topics. I enjoy these. I like to read various blogs and books (memoirs, historical novels, learn about different cultures).

What ability or skill do you wish you had that you don’t have?

I wish that I was more organized and that I would stop procrastinating. These are two areas that need significant improvement and I feel would make my life less hectic. Who knows though maybe I work better under pressure.

When you’re just relaxing and not working what is your favourite thing to do?

When I’m just relaxing there are a bunch of things I like to do. Catching a basketball game, playing basketball/soccer/volleyball, working out, going for a bike ride or hike (if it’s warm out), catching up with my friends and their beautiful babies/families, hanging out with my siblings, reading a good book. I don’t think I can pick just one.

More questions about Martial Smarts.

Please talk about the team you have

Most of my team consists of my students. My goal when teaching my weekly classes with UMMA Martial Arts is to train my students to be leaders and better than me. I give them opportunities in class to lead the warm-up exercises and after a while you really get to see them come out of their shell. Through this process, I have 3 students ranging from 15-23 who help me run my workshops. These ladies aren’t always my strongest students in terms of a technique but they are motivated, excited to share what they know, disciplined, responsible and committed. These are the qualities I am trying to foster. All of them started off timid and nervous but really grown into excellent students, fighters and teachers. The students really do respond to them and I’m happy to have them on my team. Out of the 3 students the 23 year old is a beginner but was motivated to join my regular classes predominantly to help with Martial Smarts. She attends the majority of the workshops with me, even joining me in Chennai, India in Jan 2017 where we taught self defense and workshops on healthy relationships to over 1000 women and children. She has been a great addition to the team!

I’ve had other black belts reach out recently asking to volunteer with us so this is exciting stuff. I also have male black belt friends who help me out when there are requests for workshops for boys/men.

Have you ever been in a fight? Talk about what that was like, and how this influenced you.

I started training in karate when I was around 9 years old and have been training in taekwondo for the last 10 years. It started as a mandatory lesson for my brothers and I, my mom joined us too. It then turned into a fun weekly activity where I got to learn new moves, compete and develop important character traits. As I’ve grown, I realize I was probably drawn towards the martial arts because of its close similarity to the principles of Islam. Both encourage me to be responsible, disciplined, respectful of myself, my surroundings and the people around me. I believe it was my love for Islam that fueled my love for the Martial arts.

I’ve never been in a physical fight outside of the ring. The beauty of the martial arts is that it teaches us how to control our anger and try to defuse situations rather than engaging in a physical altercation. We know what we are capable of doing and so we are ultimately responsible for restraining ourselves, being disciplined and controlling our power.

I did have various experiences that influenced me though. Once on the street I had a young man yell racial slurs at me telling me to go back to my country. He stepped towards me with his hand raised and only backed off because his girlfriend pulled him back. During a basketball game I had a guy on the sideline call me a terrorist. While at work I had someone yell terrorist as I walked by. While training at a martial arts gym I was sexually harassed. I’ve had students who have come to me with physical injuries inflicted by family members for simple things such as breaking a glass. I feel all these experiences and many more have directed me to the path I am currently on.

After completing my MSc in Global Health I realized the importance of improving accessibility to services and I definitely feel this made me think more critically about my own training and ways I could bring this beautiful art to those who need it the most but unfortunately can’t afford it, predominantly lower income/immigrant families. I used to train at a low cost after school program for most of my early years of training because we couldn’t afford to attend the main gym. Only once I had a job could I afford to pay for training. At one time I was paying over $1000 to train for a year. A lot of money for a 16 year old. After going through this, I realized I can play a small part in making this training more affordable and accessible to those who need it the most. Most of our workshops are done for free, no cost to the student. For those that can afford to pay we charge a nominal fee so that we are able to provide free workshops for those who can’t afford it. So far this model has worked well.

As a man and before that as a boy I heard phrases such as “you fight like a girl” or “you throw a ball like a girl” directed to other people. It can be incredibly coercive, the language of bullies to pressure and harass people. Even though I wasn’t the victim directly, I was harmed indirectly by being part of a coercive macho culture. I have to wonder: did you ever hear this phrase used in anger directed at anyone?

Yes, growing up all the time on the playground. Mainly with the intention of bullying the other kid. Hearing the phrase always motivated me to try harder to show them that girls actually play/throw well. I’m too competitive for it not to, and I always remember my mom telling me whatever a boy can do a girl can as well. Hearing boys say this to other boys pushed me to excel and eventually for them to try to subtype me as not the average girl. Some even called me “bro”. Just goes to show you how deep this stereotype runs.

What does that phrase FIGHT LIKE A GIRL mean to you?

The name “Fight like a girl” was actually chosen by one of the lead organizers of the event from Hart House. I hadn’t previously thought about my workshops as teaching women to “fight like a girl” but when I agreed to the name I looked at it more as defying the stereotypes entrenched within that phrase that bothered and motivated me all those years ago on the playground. By fighting like a girl, you’re actually fighting for so much more than your own physical safety. You’re fighting against the expectations placed upon us, the doubts people have when they think about us, we’re fighting for a stronger community of women, we’re fighting to empower a whole new generation of young women to dream big and overcome those obstacles that they experience solely because of their gender. We’re also fighting against cultural stereotypes and defying the odds. No one expects their martial arts instructor to look like someone like me – a woman in hijab.

This poster was for a workshop at Hart House, at the University of Toronto, which is how i first discovered Martial Smarts

But I think that’s one of the greatest parts of our workshops – showing other women it really doesn’t matter what expectations are placed upon us based on our appearance. There are so many stereotypes about Muslim women that are running rampant given the current political climate. I try as hard as I can to disprove those stereotypes and encourage my students to do the same. Islam empowered us more than 1400 years ago, many of the greatest Muslims and scholars have been women. They are successful in business endeavours and strong, powerful leaders in their communities. I aim to help women from all communities realize this potential and breakaway from limitations that others have set upon us. We will continue to fight against that. We will continue to fight to empower others.

Ultimately, every single girl/woman who has taken my workshop is part of my team. Each plays a vital role in spreading the message of self-empowerment and a safer world for women. Women who come to our workshops experience sisterhood – we break down artificial boundaries that have been set for us and aim to bring women together regardless of race, religion, educational background, socioeconomic status or ability. The women learn from each other in a safe environment, regain their confidence, boost their self esteem, learn about the extent of their power. They leave our workshops having learned that their voice is their strongest weapon. It is the most powerful tool and can and should be used in any situation where they feel uncomfortable. They also leave with a mandatory task – that of teaching everything they’ve learned to at least two other women that they know. Their mother, sister, grandmother, friend. This is how we spread our message, this is how we improve sustainability in the communities we work in.

Can we discuss FIGHT LIKE A MAN for a minute: and what’s wrong with the phrase?

I think this phrase is mainly used to instigate fights, make a boy angry or feel inadequate. It is never used with good intentions. It is used to ignite a flame in little boys/teens that in the end is counterproductive and quite often destructive. By using this phrase, and hearing this phrase from a young age, little boys are taught the wrong way of dealing with conflict. They aren’t taught the appropriate way of reacting to a negative situation, how to use their words or why fighting is a bad idea. A more appropriate phrase would be “fighting doesn’t solve anything, it’s better not to fight at all”. It is always better to solve a disagreement using your words and to make it clear that you don’t want to fight. If however you are attacked, I believe it is appropriate to fight back with the goal of getting away, not winning a fight.

Is there anything you’re dreaming of doing with Martial Smarts in the future?

We’ve already done a short documentary that was produced in early 2016. It has been showing around the world. Played first at the Global Impact Film Festival in Washington DC. Has since played in various cities in the US, in Toronto, the UK, Ukraine and China. It’s called “The Good Fight” by Chrisann Hessing, a local Toronto filmmaker. It was quite an empowering experience all around given that Chrisann is quite young and this was her first project directed, produced, filmed and edited all on her own. I’m really glad I was able to help her achieve this goal.

We’ve also run workshops I’m Bangalore, Chennai, Sri Lanka, Dar es Salaam and Maryland. There have been numerous requests from other cities and hopefully we will make our way around and train/involve people locally to continue this work.

My goal for Martial Smarts is global. I have connected with a couple of women doing similar work around the world and I think that is the most exciting part. Ultimately, if we can change the life of even just one woman, all the effort we have put in has been worth it.

Please talk about your martial arts training and the connection to Martial Smarts

My training has predominantly been in karate and taekwondo (black belt in both). I have done some training in BJJ, must Thai and boxing. I believe these martial arts all teach effective methods of defending yourself and I teach a bit of everything in my workshops. There are women who train in all of these arts and are very successful in their art. I don’t believe that martial arts are inherently sexist at all but rather the philosophy is for anyone willing to push themselves to listen to the body and learn how to use their bodies effectively. This is irrespective of gender or ability. You learn how to use what you have and this embodies the beauty of the martial arts. I am definitely more of a traditional girl and I try to bring my love for this art to other women.

Is there a teacher or influence you’d like to acknowledge?

There are a few teachers who I have admired for their perseverance, kindness, dedication and commitment.

Sensei Jared- my first martial arts teacher, taught me karate for several years. Encouraged me and pushed me to get better. Made accommodations for my family with no questions asked that allowed us to keep training. Was studying medicine too and showed me that it is possible to combine both. Ultimately showed me the importance of kindness and how to be a good teacher.

Sensei Debbie Markle – my first female karate instructor at Northern Karate Schools. A great inspiration for me as she continues to train hard. Showed me that it is possible to achieve a high rank in the martial arts as a woman.

Master Abdullah Sabree – my first taekwondo instructor. Started the first Muslim Martial Arts Club in Toronto to help youth in the Jane and Finch area stay out of trouble. Opened up his club to people from all religions and ethnicities. Offers his classes at a nominal rate in various mosques around the GTA with the goal of supporting the community. Taught me the importance of showing up every class no matter what the weather is like or whether you have no students show up. Once people see your dedication and skill they will show up in droves. He was right.

*******

Martial Smarts Workshops occur regularly. There are some in May that are already full and therefore not open to the public. The best way to find out is through social media via their facebook and instagram pages which are regularly updated.

I hope the audience sees that. The audience is a part of it too. The audience is watching. The audience is a presence. I don’t go for this thing that the audience is always anonymous in the dark, that we’re all the same: especially in a place like the Four Seasons Centre, where there are rings and tiers. The strata, a sense of hierarchy. I just wanted to reflect that in the show.

I hope the audience sees that. The audience is a part of it too. The audience is watching. The audience is a presence. I don’t go for this thing that the audience is always anonymous in the dark, that we’re all the same: especially in a place like the Four Seasons Centre, where there are rings and tiers. The strata, a sense of hierarchy. I just wanted to reflect that in the show.