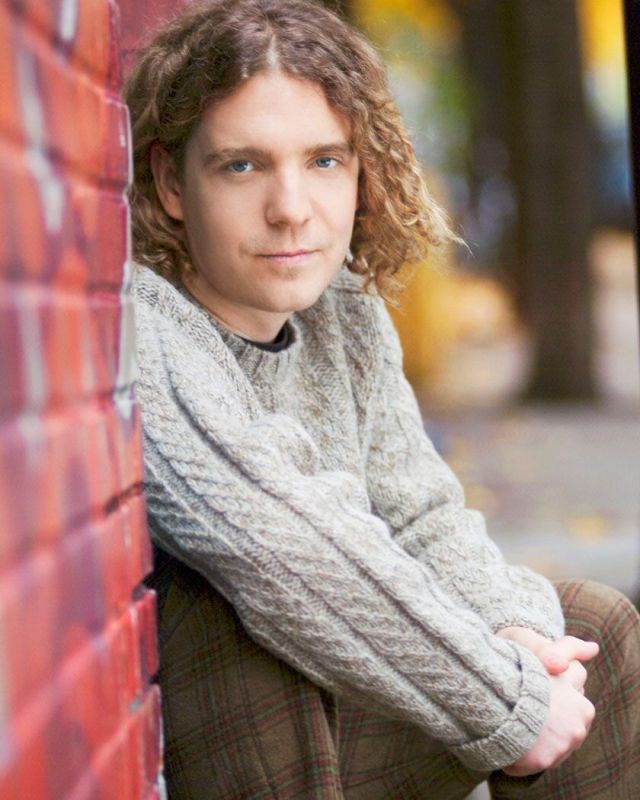

John Abberger, one of North America’s leading performers on historical oboes, is a familiar face locally as the principal oboist with Tafelmusik (bio), often playing key solos in concerts as he did just last week. John is also Artistic Director of the Toronto Bach Festival.

I wanted to find out more about John and to ask him a few questions about the fourth annual Bach Festival coming up May 24th -26th 2019.

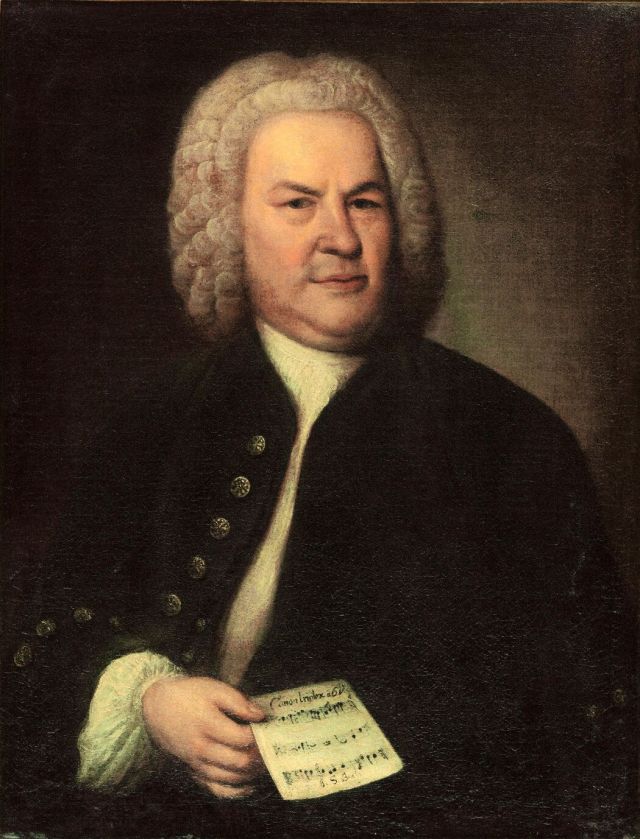

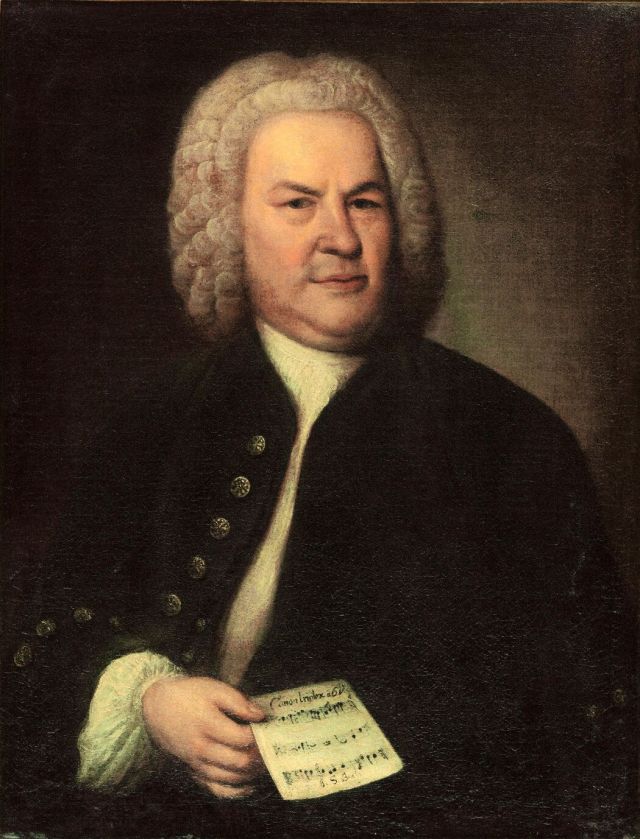

John Abberger

1) Are you more like your father or your mother?

To be honest, I feel that I am an interesting combination of my parents, without any one of them predominating. My father was a thoughtful and somewhat shy person. I think in my youth I took after him more, but as I grew in my career as a musician it was necessary to find a way to overcome that diffidence, and the example of my mother provided a powerful resource upon which I could draw.

2) What is the best or worst thing about what you do?

Pretty much all of the things I do have good and bad aspects. For example, I love playing the oboe, but making reeds, not so much. But you can’t play the oboe (on a high level, anyway), without making reeds. It’s part of playing the instrument. At this point the Bach festival is being run by myself and a couple of other people who work on a very part-time basis, or who are board members volunteering their time. There are many tasks to be done, and most of them I find interesting, but there are times when I feel overwhelmed with the volume of work to be done.

(Not sure I’ve answered your question).

3) Who do you like to listen to or watch?

I don’t listen to music a lot at home. When I do, I like to listen to music I am unlikely to perform myself , such as the keyboard works of Bach, and I also occasionally listen to some of the later repertory that I don’t get to play anymore, such as Strauss and Mahler and Shostakovitch. I‘m a horrible classical music nerd, though. I like good jazz, but I don’t listen to it at home.

I love going to live theatre which I do as much as I can fit into my schedule, and I have lately been sampling some of the amazing wealth of high-quality television that is available now.

4) What ability or skill do you wish you had, that you don’t have?

I definitely wish I could play the keyboard with some minimal level of competence. I actually started my musical life taking piano lessons when I was 7, but it never seemed to captivate me the way orchestral instruments did later, and I abandoned it after a few years.

5) When you’re just relaxing and not working, what is your favourite thing to do?

Cooking, reading, going to the theatre, watching some of the above-mentioned television dramas with my wife.

More questions about preparing the 4th Annual Bach Festival May 24-26.

1) You wear several hats, playing oboe for Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, in the productions for Opera Atelier and annually organizing this Festival. Of the many things you do, from practicing your oboe, performing on the oboe here and abroad with other groups such as the American Bach Soloists & curating a festival: what’s the hardest job for you, and what’s the most fun thing you do?

I feel very fortunate in that I mostly do things that I really enjoy. I love playing the oboe, with Tafelmusik particularly, but also with other groups. Making reeds can feel like a chore, but that’s part of playing the oboe. I love the work of creating each festival, and the work of the musical preparation that goes into the artistic direction. There are some purely administrative tasks that I could do without, but that’s a bit like making reeds for the oboe, it’s part of the job. What’s challenging for me is when all these worlds collide, and I don’t have time to enjoy the tasks that I love because there are deadlines to meet. But that’s life, isn’t it?

2) Your Bach Festival is growing, now with the addition of concerts at the Black Swan Tavern on Danforth. Can you describe what we’d hear in the Tavern?

We are very excited to be adding this new festival event this year. We want to do something more outside-the-box, we want to present some interesting Bach-inspired repertory, and we want to create a different kind of experience for our audience, and perhaps attract some new listeners outside of our typical audience.

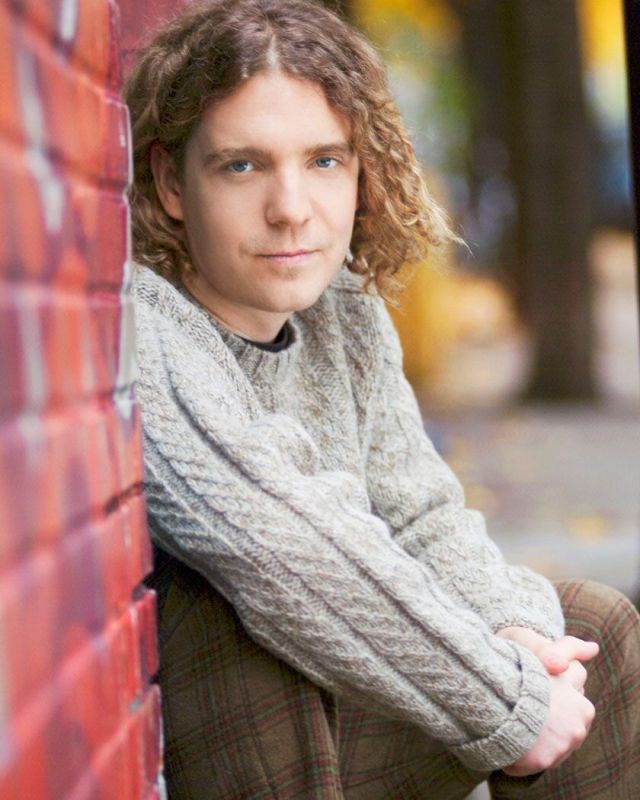

Elinor Frey (photo: Elizabeth Delage)

The concert will feature Bach’s Sixth Suite for solo cello, which was written for a 5-string cello (rather than the usual 4), and this will be paired with two works that Elinor Frey has commissioned to be written specifically for this 5-string instrument. This will be our first venture outside of the typical concert format, and we are eager to see how it is accepted by our audiences and by the community. Bach performed a lot of his music in a coffee house in Leipzig, so it’s actually a good example of historically informed performance in action. I hope people will feel free to keep drinking, and if they want to talk quietly and get up whenever they like, I think that will be great. The hallowed silence and reverential devotion for the musical art is a Victorian construct. I don’t think that aesthetic applies generally to the way music was performed in the 18th century.

3) You describe The Mission of the Bach Festival as follows:

“Seventy per cent of Bach’s music is unknown to the average music lover, yet his music stands out as one of the most profound expressions of the human spirit in western art music. The mission of the Toronto Bach Festival is to introduce audiences to lesser-known works of Johann Sebastian Bach, while presenting perennial favourites, all in historically informed performances.”

Could you give examples from your program?

Our opening concert this year is a great example. It combines one of the most iconic of Bach’s works, the Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, with two cantatas. When it comes to the cantatas, the 70% figure goes down to about 97%! Of the more than 200 cantatas that Bach wrote, only about 5 are well-known. BWV 152, which opens the programme, is even more of a rarity, and is seldom performed because of its unusual instrumentation, which includes viola d’amore and viola da gamba.

The Lutheran Masses are another good example. The music is all recycled from cantata movements, so they are very similar to the Mass in b minor in that sense, but these works are not performed very often as they are overshadowed by that great work. And we are including on that programme an independent setting of the Sanctus, one of a small handful of individual sacred vocal works that seldom find their way onto regular programmes of Bach, perhaps because they are not part of a larger work.

4) Please tell us about the program in the Bach Festival this year.

Harpsichordist Luc Beauséjour

Friday, May 24, 8 pm

BRANDENBURG 5

Luc Beauséjour, harpsichord soloist

Julia Wedman, violin soloist

Directed by John Abberger

Violinist Julia Wedman

Programme:

Tritt auf die Glaubensbahn, BWV 152

Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, BWV 1050

Concerto in A minor for Violin and Strings, BWV 1041

Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn, BWV 23

Alto Daniel Taylor

Hélène Brunet, soprano

Daniel Taylor, alto

Nicholas Weltmeyer, tenor

Joel Allison, bass

Bass Joel Allison (Photo: Ian McIntosh Photography)

Alison Melville, recorder

John Abberger, oboe

Marco Cera, oboe

Thomas Georgi, viola d’amore

Julia Wedman, violin

Valerie Gordon, violin

Patrick Jordan, viola

Felix Deak, violoncello and viola da gamba

Alison Mackay, bass

Joelle Morton, violone

Christopher Bagan, harpsichord

Saturday, May 25, 3:30 pm

LECTURE

Bach and the French Style

Ellen Exner, lecturer

New England Conservatory of Music

Saturday, May 25, 5 pm

HARPSICHORD RECITAL

Bach and the French Style

Including

English Suite No. 3 in G minor, BWV 808

French Suite no 5 in G major, BWV 816

Luc Beauséjour, harpsichord soloist

Saturday, May 25, 9 pm

LATE NIGHT CONCERT

Elinor Frey, violoncello

Featuring the Suite No. 6 in D major, BWV 1012

with new works by Isaiah Ceccarelli and Scott Edward Godin.

John Abberger (photo: Sian Richards)

Sunday, May 26, 3 pm

LUTHERAN MASSES

Directed by John Abberger

Programme:

Mass in G major, BWV 236

Sanctus in D major, BWV 238

Mass in F major, BWV 233

Hélène Brunet, soprano

Emma Hannan, soprano

Daniel Taylor, alto

Simon Honeyman, alto

Lawrence Wiliford, tenor

Nicholas Weltmeyer, tenor

Joel Allison, bass

Matthew Li, bass

Scott Wevers, horn

Christine Passmore, horn

Marco Cera, oboe

Gillian Howard, oboe

Dominic Teresi, bassoon

Julia Wedman, violin

Valerie Gordon, violin

Cristina Zacharias, violin

Gretchen Paxson, violin

Patrick Jordan, viola

Felix Deak, violoncello

Alison Mackay, bass

Christopher Bagan, harpsichord

5) You’re so busy! Do you find you have enough time to practice your instrument and to learn new works? Are you one of those artists like Horowitz who doesn’t practice very much? Or do you play regularly.

I don’t think there are any performing musicians (including Horowitz) who don’t practice regularly. It’s part of the job. I enjoy learning new works. That’s when I really recharge as an artist. I have been studying Bach’s works for my entire career, and although I have to look at them a little differently when I am preparing to direct a performance, it’s all a part of a process that I find intensely fascinating.

6) Has the festival with its focus on lesser-known works changed your thinking about what you play?

I definitely think performing more of Bach’s works provides a larger context for us to evaluate his achievement as a composer. Hearing and experiencing more of his music deepens our understanding of all of his works, both the familiar and the less familiar. I also think hearing more north German sacred music from the generations before Bach can really enrich how we hear his music. This is why I included the Passion setting by Heinrich Schütz in last year’s festival, and I hope to perform more north German sacred music at the festival in the future.

I’m not really one of the diggers, though. There are amazing scholars who devote their careers to that kind of thing, and it’s a time-consuming business, to be sure, to say nothing of the expertise necessary to do that kind of research properly. What I do is sift through the results of their work. But with Bach it’s all been examined in immense detail over the last century or so.

7) In the spirit of your festival, Are there any lesser known composers or works that you wish Tafelmusik might undertake?

Just as I feel about the Bach’s lesser known works enriching our understanding of his more familiar works, I think the same applies to larger repertories. Like any musical organization, Tafelmuisk has to balance the interests and wishes of the artistic director with the need to sell tickets to the concerts. That having been said, I think it‘s really great when we can explore lesser known composers. Even when the music isn’t “first-rate” as defined by the standards of Bach and Handel, it can really be interesting to hear, and it definitely deepens our understanding of what makes Bach and Handel so great. I’d apply this not only to early 18th century “baroque” music, but also to early classical and later 18th century music. Mozart and Haydn are great composers, but what makes them so great? Hearing more of their contemporaries can really help us to understand what makes them great, and the audience will attain this understanding on an intuitive level, without a lot of musical analysis terminology (very useful to musicians, but a real turn-off to the average listener).

8) Is there a teacher or influence you’d care to name that you especially admire?

I guess I’d say the historically informed performance movement itself has been a profound influence on the direction my career has taken. From its roots in Europe in the 1970s, it was just beginning to make its way to North America in the early 1980s. When I finished my Masters degree at the Julliard School in 1981 I was looking for an artistic direction, and my love of Bach and baroque music in general naturally led me to explore this field, which was just beginning to bloom in New York and Boston and Toronto. I immediately felt a deep attraction to the idea of applying historical research to bring music from this period alive for audiences today. I’ve never looked back. Bach’s music (and that of his contemporaries) makes so much more sense performed this way, and I believe it gives performers a better way to communicate its profound beauty to our listeners. For me it continues to be a wonderful adventure today, all these years later.

*******

John Abberger and the 4th Annual Bach Festival are coming to Toronto May 24-26. Just click for further information about the Toronto Bach Festival.