Ten days ago I posted something about erotic opera, especially as it pertains to Actéon, an opera that is to be presented again by Opera Atelier beginning Thursday October 25th at the Elgin Theatre.

Near the end of that post from Oct 12th I said:

I feel a special connection to Actéon. I used some of Charpentier’s 17th century opera in my operatic adaptation of Venus in Furs written & presented in 1999. It seemed too good to be true to be able to adapt something erotic into another erotic opera, to present a specimen of voyeurism, when the main character is a bit of a voyeur himself.

Prepare to have your buttons pushed.

Artist of Atelier Ballet Edward Tracz poses as the stag in Actéon (Photo: Bruce Zinger)

My adaptation of Venus earned me a keynote address at a conference at Western University. That sounds pretty good, doesn’t it! But were they inviting me to talk about my libretto? Or the score? Or operatic dramaturgy?

No, no and no.

I was instead invited to talk about erotica and pornography. I think it’s still a very fertile subject for investigation, whether we focus on opera or on any other artistic realm. It’s lurking in Hadrian for example, although it is a very thoughtful and measured erotica from Wainwright.

But sometimes one doesn’t want to be acknowledged as an expert. I was pretty cagey, and maybe a bit too coy in how I approached the project. I am not a pornographer, and Venus in Furs is not designed merely to titillate: well that’s not all it’s doing. It’s a work of art, an adaptation of a novel, admittedly a novel that gave the name to one of the two best-known sexual perversions. There’s that Marquis de Sade fellow and his sadism, and then there’s Leopold Sacher-Masoch, and masochism.

The words are regularly employed in the metaphorical sense. We hear of people who are sadists because they inflict pain upon someone. And we also hear of people who must be masochists because of the pain they endure.

But they also have literal use to describe obsessive behaviour, and of course in the realm of BDSM. (and need I remind you what those initials actually signify?)

Why would one set such a text as an opera?

Frankly I’m astounded that it hasn’t been done more frequently. I looked at Strauss’s Salome and thought that the use of a forbidden text helped propel the composer to a kind of notoriety, the complex psychology of the story infusing the music with something feral and insane. Or more properly, I suppose we’d call it expressionistic. I mostly prefer his tone-poems to his operas in point of fact, heretical though that may be to proclaim. But I’m simply explaining a rationale, a modus operandi. The Sacher-Masoch novel is very simple. And I was intrigued by it because for once it’s a story where the passionate subject is male rather than female. I had zeroed in on two stories for awhile, and one had Venus in the title while the other was Aphrodite, namely Pierre Louys’s novel, which I had adapted in the 1990s (but that’s a whole other story…). I had thought they would make an interesting pair both for their titles (imagining them sharing an evening, as “Venus & Aphrodite”), but also as a pair of stories where there is a male-female power struggle between the protagonists.

My keynote referenced Salome and also DH Lawrence’s The Virgin & the Gypsy. The novella furnished a handy metaphor that I used in my talk, to discuss the process of attribution whereby a society decides something is forbidden or permitted. Lawrence brings us a repressed family in a town with a river and a dam. When the dam breaks there is a kind of return to nature, as true feeling briefly triumphs over the artificiality of society. I believe that meanings such as “good” or “humorous” or “beautiful” are naturally in the eye of the beholder, who makes an attribution, a kind of interpretation of data. Some of these are conditioned by societal norms, whereby we decide what is forbidden or acceptable to see and hear.

When I encountered the 17th century opera Actéon by Charpentier in an earlier version from Opera Atelier, it was an adaptation of Ovid, a cautionary tale. The more I thought about it, though, the more I wondered about its reception, especially in the century of its premiere. I pictured an audience giggling with delight at what happens to poor Actéon:

- Peering out of the bushes at the goddess Diana

- Transformed into a stag when she objects

- Pursued and killed by his own hounds

The man becomes an animal. We see something similar in The Odyssey when the sailors encounter Circe, who turns them into swine. Odysseus resists her magic with the help of the gods and some herbs, but he would surely be as susceptible as any of his men that became pigs. Did Charpentier expect that the audience watching Actéon –the voyeur, the man who becomes an animal and dies pursued by his own hounds—would giggle nervously, perhaps getting excited at this sexual opera? I have to think so. The action is very blatant.

I had at least a couple of reasons to use this opera in my adaptation. For one thing, I was busy almost exactly twenty years ago at what was then known as the Drama Centre at the University of Toronto:

- In the fall of 1998 I entered the PhD program, while holding down a full time job. The Director of the Centre ruled that I met residency requirements by using an “inclusive” rather than “exclusive” definition. So long as I made it to conferences etc? I was satisfying their requirements, and never mind that I was also working at a full-time job at the university.

- In the summer I made an adaptation & translation of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera based on Pushkin’s play Mozart & Salieri, expanded somewhat with additional music by Mozart, including Alex Dobson & Wayne Line each getting a performance as Salieri, and Jay Lambie in both performances as Mozart.

- Immediately after (September-October) I wrote and performed original music for Orpheus by Cocteau, directed by Aleksandar Lukac, a show that was done with a different cast the following summer in the Fringe Festival.

Aleksandar Sasha Lukac, director of A Flea in Her Ear in 2017

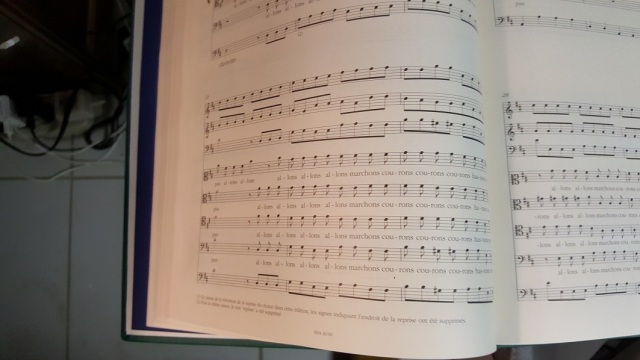

- In the spring of 1999, when I heard that the Festival of Original Theatre (aka “FOOT”) was to have the theme “Obsessions & Possessions”, I hastily proposed Venus in Furs even though the piece was not even begun, let alone written. I sketched out a libretto sometime around Easter, finishing the composition of the last of the music partway through the rehearsal period. Can you say “in a hurry”? and so the opportunity to incorporate an existing chunk of music was irresistible, inevitable: because of the time factor. Later in the opera, the chorus’s “allons allons marchons courons” became a leit-motiv for Severin’s adventures. The cast included Michael Sawarna and Sarah Gartshore and was directed by Sasha Lukac.

“Allons allons…”! And we did.

- I would go on to write another opera the following year (but that’s a whole other story…).

I cannot deny that when I was doing my MA and later my PhD, I was less interested in academic objectives than the practical program, which gave me a theatre to play in. During my MA I did a few shows a year. In the PhD for awhile I became very serious about the thesis, especially when my supervisor asked me to stop composing, and at least a couple of professors mocked me for having way too much fun, while suggesting that I needed to stop & get serious. I wish I had been more lucid and shown more backbone in response: because I’d always known at the beginning that I was more interested in using the theatre as a laboratory to explore operatic dramaturgy (my thesis topic after all) than in becoming a genuine professor. I was very conflicted.

The blog itself has been a funny way of reconciling these things. I started it back when I was thinking I would finish the thesis. In 2011 and 2012 I still thought I might finish. And more recently I was approached by a very kind soul to apply for a job: for which I didn’t nearly have the qualifications. The essence of the blog is to help me find my true voice. In the process I have been reconciling my conflicted feelings, a way to be academic and studious while making my own rules.

It’s amazing to watch the video of something written & performed decades ago, the recording like time-travel. I am working on a revision, planning to revive Venus in Furs in the next year, with Sasha Lukac again directing. I’ll let you know when it happens.

In the meantime? Opera Atelier present their double-bill of Charpentier’s Actéon and Rameau’s Pygmalion, opening October 25th at the Elgin Theatre.

Meghan Lindsay poses as the statue in Pygmalion (Photo: Bruce Zinger)